Originally posted April 2017. We’re reposting this in light of California’s recent decision to prevent the renewal of contracts with for-profit prison companies.

Last month, Attorney General Jeff Sessions reinstated the use of private prisons in the federal system. This move is welcome news to top corrections corporations such as CoreCivic, but human rights activists are concerned about this shift. Opponents claim that these corporations bring in large profits while their prisons remain rife with safety and healthcare deficiencies, as well as underpaid employees. While these concerns are important to consider, the private prison industry represents a small segment of the American correctional system. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, only 17% of inmates in federal prisons and 7% in state prisons were held in private facilities in 2015.

During their initial inception, private prisons were believed to be a cost-effective option that could provide better services than government facilities. Despite these goals, much of the current evaluative research suggests that private facilities are no more cost effective than public facilities. Likewise, private prisons appear to perform worse in reducing recidivism than public correctional facilities and have similar (and sometimes worse) conditions than public facilities. In contrast, some evidence suggests that private prisons may be less overcrowded. Due to these ambiguities, scholars of the privatization debate are calling for more research into the qualitative differences between the private and public sector of prisons.

- Andrea M. Lindsey, Daniel P. Mears, & Joshua C. Cochran. 2016. “The Privatization Debate: A Conceptual Framework for Improving (Public and Private) Corrections.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 32(4): 308-327.

- Matthew D. Makarios, & Jeff Maahs. 2012. “Is Private Time Quality Time? A National Private–Public Comparison of Prison Quality.” The Prison Journal 92(3): 336-357.

- Andrew L. Spivak & Susan F. Sharp. 2008. “Inmate Recidivism as a Measure of Private Prison Performance.” Crime & Delinquency 54(3): 482-508.

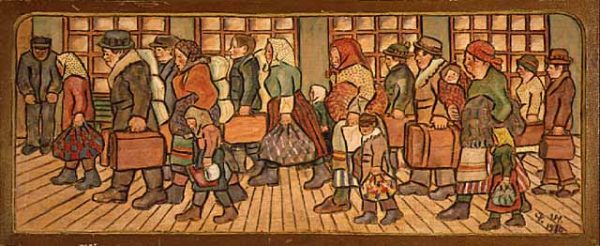

Regardless of their effectiveness, research suggests that the demographic composition of private prisons is racially disparate. In an analysis of adult correctional facilities in 2005, private prisons had significantly fewer white and more Hispanic populations when compared to their public counterparts. As to why racial and ethnic disparities exist, research points to the role of private prisons in immigrant detention, which has lead some scholars to argue that the private prison industry is just a small segment of a massive immigrant industrial complex. This line of research posits that this complex perpetuates the criminalization and stigmatization of immigrants, especially among Latinos, and as a result comes at a significant cost to immigrant families and communities.

- Brett C. Burkhardt. 2015. “Where Have All the (White and Hispanic) Inmates Gone? Comparing the Racial Composition of Private and Public Adult Correctional Facilities.” Race and Justice 5(1): 33-57.

- Karen M. Douglas and Rogelio Sáenz. 2013. “The Criminalization of Immigrants & the Immigration-Industrial Complex.” Daedalus 142(3): 199-227.

- Tanya Maria Golash-Boza. 2015. Immigration Nation: Raids, Detentions, and Deportations in Post-9/11 America. Routledge.