When an arrest is made, all eyes are on the person in handcuffs. At a trial, the jury focuses intently upon the defendant. And when the prison door slams shut, we envision the solitary individual “doing time” far from the outside world. The “outlaw,” the “offender”: even the words commonly used to describe people who are arrested, sentenced, and incarcerated suggest loners, isolated beings whose only interactions involve other lawbreakers, crime victims, and police and correctional officers.

And yet, as social scientists turn their gaze to the surrounding streets, residences, courthouse hallways, and correctional visiting rooms, we expand our view of who is affected by the criminal justice system. We are alerted to children hiding in closets during a parent’s arrest or coming home from school to an empty apartment. They may eventually wind up in the custody of grandparents, in the child welfare system, or, worse still, in juvenile custody. We become aware of mothers and fathers whose doors are broken down in the dead of the night and who are held at gunpoint in their bedclothes as the police search for their fugitive sons or daughters. We realize that, like everyone, people who are suspected or convicted of breaking the law have families, friends, and neighbors who experience profound psychological, social, economic, and health consequences when they have an outstanding warrant, get sent to jail, or come home from prison with a felony record. Arresting, sentencing, and incarcerating one person reverberates through familial and social networks. Like the cue ball breaking the rack in billiards, the punishment of one person sends many others spinning off in multiple directions.

Ripple Effects

In the United States, the need to establish what sociologist Robert Sampson calls a “social ledger of incarceration’s effects”—an assessment of its impacts on personal and family relations and neighborhood stability—has become urgent. The number of people coming into contact with the criminal justice system has ballooned. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), there were roughly 380,000 people behind bars in the U.S. in the mid-1970s, and some of the nation’s most distinguished criminologists predicted that prisons were on their way to extinction. Instead, there now are over 2.2 million people in jail or prison on any given day, and millions more cycle through correctional facilities each year. Given the available data, we cannot know precisely how many family members, social intimates, and neighbors are affected by these events, but we can begin to make an educated guess. As one example, BJS statisticians Lauren Glaze and Laura Muraschak report that just over half of the nation’s prisoners reported that they were parents to an estimated 1.7 million minor children in 2007; that would mean 2.3% of the U.S. population under age 18 had a parent in state or federal prison. (Keep in mind, these numbers do not include the children of people who were in local jails; many more people go to jail than to prison because prisons generally are reserved for convicts serving longer sentences for more serious crimes, while jails hold anyone awaiting judicial disposition and those convicted of minor offenses.)Criminal justice involvement is extremely unevenly distributed across the population. Indeed, sociologist Loïc Wacquant argues that rather than “mass incarceration,” which implies a generalized experience concerning broad segments of the population (as with mass media or mass transit), the U.S. penal state has created a phenomenon of “hyperincarceration” by targeting policing and punishment policies “first by class, second by race, and third by place.” In other words, the people who are most likely to wind up under arrest, facing a prosecutor, and sitting behind bars are overwhelmingly those who are extremely poor (two thirds of jail inmates come from household living under one half of the official poverty line), African American, and reside in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage and dysfunctional public institutions. By extension, the people who are most likely to experience a family member’s incarceration are also disproportionately impoverished African Americans. Sociologist Christopher Wildeman calculated that black children born in 1990 had a 25.1% risk of having their father imprisoned by the time they were 14 years old, compared to a 3.6% risk for white children born in the same year. Tellingly, the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study and other poverty research not focused on incarceration per se has provided critical data about the reach and scope of people affected by the criminal justice system through their connection to arrestees and inmates. Indeed, incarceration has become so prevalent among the nation’s poor that it influences every institution and status, from employment and education to housing, public health, and family formation.

“Secondary Prisonization”

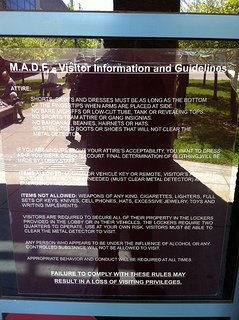

My interest in what I call the “repercussive effects” of incarceration began when I worked at the San Quentin State Prison visiting center in the late 1990s. San Quentin is located in northern California, directly across the bay from San Francisco, and it’s the oldest prison in the state. California law mandates that each prison has a center to assist visitors, a primary function of which is to provide clothing for people to borrow if they arrive dressed in garments that are prohibited by the correctional facility. These items include anything that prisoners or prison officers wear, such as blue jeans, white t-shirts, button-up chambray shirts, and the colors khaki, bright yellow, and army green. Visitors must also pass through a metal detector before being allowed into the prison. (For the dozen years I spent at San Quentin, the machine was calibrated so sensitively that the underwire in a bra would set off the alarm and trigger denial of entry.)

My early days at the visiting center were regularly punctuated by people—mainly wives and girlfriends, mothers and sisters, often with young children—showing up at our doorstep in tears, in anger, or in sheer bewilderment. They couldn’t figure out why the outfit that they wore to work or bought to look nice for their visit, or even that had been judged “acceptable” by a prison officer last week, wasn’t permitted as visiting attire today. Over time, as I led them to the rack of donated, slightly misshapen, definitely outdated clothing and tried to help them find a garment close to their size, I began to think of the descriptions in Erving Goffman’s Asylums. In this book, Goffman writes how inmates are “shaped and coded into an object that can be fed into the administrative machinery of the establishment, to be worked on smoothly by routine operations.” This was particularly salient when a new visitor learned the ropes. The vibrant, chatty woman who arrived an hour early for her visit later had a face creased with anxiety when she returned with instructions to change out of her dress, became weepy when she was sent back a second time to borrow a soft-cup bra, and seemed melancholy and withdrawn when she finally returned to give us back the borrowed clothes. Social theorist Michel Foucault aptly described such processes as a dismantling of the self, a conversion into a “docile body” suited to carceral authority.

Eventually, my two years of employment at the visiting center became the practical guideposts for my dissertation fieldwork at San Quentin and the book that grew out of it, Doing Time Together: Love and Family in the Shadow of the Prison. As I deepened my observation and analysis of women’s experiences maintaining contact with an incarcerated loved one, I discovered other parallels within the classic literature on inmates. I was inspired to return to sociologist Donald Clemmer’s The Prison Community, particularly his concept of prisonization. Clemmer likens the prisonization of inmates to the Americanization of immigrants, describing it as the process of adapting to the correctional environment by learning the lingo, changing one’s appearance and behavior, and generally “wising up” to the demands and expectations of the penal institution. Although the women I studied had more liberties than the men they were visiting, they, too, “wised up” to the penitentiary culture as they learned what clothes to wear (and the wisdom of bringing a spare outfit, just in case), which officer would cut them a break, how to get around the limit on the number of packages they could send to their loved one, and what time of day they could expect a collect call from the cellblock. Through their contact with the prison, women with a loved one inside underwent “secondary prisonization”—a less potent but still powerful process derivative of and dependent upon the primary prisonization of the men they regularly visited.

The repercussive effects of the criminal justice system aren’t limited to the United States. They have been studied in numerous countries, and they manifest differently according to political and cultural context. For example, sociologist Manuela da Cunha has examined women’s incarceration in Portugal, where the combination of scarce facilities for female prisoners and patterns of drug trade involvement in families has resulted in mothers, daughters, and sisters being locked up together. Without enough female family members left to care for children on the outside, the younger generation is brought into the prison. They live with the women while they serve their sentences, giving new meaning to the concept of a “family unit.” Comparative and international research on incarceration’s impact on family and social life highlights each country’s peculiarities, but it also stimulates thinking about potential policy alternatives.

Prison as a “Domestic Satellite”

In my fieldwork, I saw how women’s adaptation to San Quentin helped them navigate the shifting dictates and arbitrary rules of the prison. However, it also blurred the line between women’s private and prison spheres, at times creating a seamless crossover between the two. For instance, women who couldn’t afford a separate wardrobe of prison-specific outfits started to consider, “Can I wear this into San Quentin?” before purchasing any new item of clothing. In time, their everyday clothes were “penitentiary clothes,” conforming to the regulations imposed by the correctional authorities. Likewise, women learned to organize their work, meals, childcare, and social schedules around the prison’s visiting days and hours, as well as the periods during the day when men were allowed to make phone calls. Their daily routines became synchronized with the institution’s timetable, more attuned to administrative requirements than the comfort and convenience of non-incarcerated women and children.

Distinctions between private and prison life eroded further for those women who tried to keep their loved ones closely involved in the rhythms of family life by “relocating” meals, celebrations, and other meaningful activities into the San Quentin visiting areas. Food often became a focal point, and women adjusted meal times to eat with their loved one during visits, even though this required making do with the expensive junk food available from the prison vending machines. For special occasions, visitors taught each other how to make “cakes” with vending machine items—for instance, by frosting a cinnamon roll with the cream cheese that came with a bagel and topping it with a chocolate bar melted in the microwave. Sometimes women tried to share meals prepared in their own kitchens: one Thanksgiving, a woman pressed turkey, stuffing, and side dishes into sandwich bags, concealed the bags in her pantyhose under loose trousers, and surreptitiously reassembled the feast in the visiting room before serving it to her husband.

Although these creative efforts were perhaps more pleasant than being forced to change clothes or think about San Quentin’s regulations before buying a new shirt, they still demonstrate how women undergo secondary prisonization by having sustained, close contact with the penitentiary. The women transformed the prison into a “domestic satellite” in which family life was enacted. This, in turn, shifted women’s expectations and actions over time, to the point that those who had long histories of visiting incarcerated loved ones expressed how the prison began to feel like “home.”

Seeking Quality Time

The notion that the penitentiary feels like home carries certain logic for those who spend twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week for years or decades behind bars. But it requires deeper analysis when non-incarcerated people say the same. Listening to women talk about what felt “homey” to them and was enjoyable about their visits emphasized how they had learned how to navigate San Quentin’s rules, become accustomed to its routines and requirements, appreciate the limited sociability it anchored, and create moments of levity, celebration, and togetherness within and around its walls.

Finding out about the conditions of women’s lives away from the prison added another dimension, showing how deeply the criminal justice system infiltrates the lives of the poor. Women told me how they and their children lived with fear, uncertainty, and anxiety in neighborhoods replete with violence. Some women visitors were homeless; others resided in cramped quarters without adequate space or beds for everyone. Many women worked long hours, often covering the night shift, worrying about the children they had to leave unattended. These portraits of outside lives were filled with cumulative economic hardships, a striking lack of social services, and unrelenting neighborhood violence. They shed light on the sense of reprieve women had when they visited San Quentin: in contrast to the danger and tumult of their everyday existences, having a place to sit down in safety, share a sandwich with a loved one, and hold a leisurely conversation while watching their kids play in the corner made women feel like they were taking a break.

One further distinction women underscored between their “inside” and “outside” lives were the changes they saw in their loved ones during incarceration. Many visitors spoke candidly about their partners’, sons’, brothers’, and friends’ struggles with alcoholism, drug use, and mental health issues, and how there was nowhere to turn for help in their neighborhoods. In the absence of treatment programs or social workers they could turn to on the outside, men’s problems often would escalate to the point that they were destabilizing and even dangerous for their families. Paradoxically, then, men’s incarceration provided a sort of “relief” in that it eased the burden for sheltering, feeding, and managing the behavior of difficult men who needed, but couldn’t get, professional help.

In addition, the men typically showed appreciation to those who took the time and spent the money necessary to keep in touch. Prisoners are highly constrained in what they can give to others: they make little or no money, and even hugs and kisses (let alone sex) are restricted. The gift of communication thus became the primary means by which men reciprocated women’s caretaking: they listened attentively, asked questions, remembered details, talked for hours during visits and phone calls, and wrote frequent and lengthy letters in which they expressed their emotion and affirmed their commitment. Women remarked on the difference between men who were “ripping and running” on the streets, with little time or inclination to exchange a word, and those same men eagerly engaging in long, in-depth dialogue when they were in San Quentin. Although women at times felt cynical or sorrowful about the circumstances surrounding these transformations, they acknowledged that, without more economic, social, and psychological support structures in their neighborhoods, visiting rooms would continue to be the main places they could spend “quality time” with their loved ones. Prison was seemingly the only institution that could provide these women and their families with the stabilizing—if also degrading—support they needed.

No Release in Sight

Secondary prisonization helps us understand how people who maintain close relationships with prisoners can become “quasi-inmates” as they learn and respond to the constraints and dictates of a correctional facility. When visitors must completely reorganize their social and family lives around the rhythms of prison life, their efforts to maintain close ties with loved ones intensify the process of secondary prisonization. Prisons play a critical role in this process, but so too does the dearth of social and economic support outside of prison walls—support that might keep people out of prison and feeling safer, healthier, and less stressed within the walls of their own homes. This article hardly begins to address how dramatically one person’s incarceration affects the lives of those to whom he or she is connected.Recommended Reading

Donald Clemmer. 1958 [1940]. The Prison Community, 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Rinehart. The classic text introducing the concept of “prisonization.”

Megan Comfort. 2007. “Punishment Beyond the Legal Offender,” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 3(1):271-296. A review of studies on the kinship webs and social networks of those subject to criminal punishment.

Lauren E. Glaze and Laura M. Muraschak. 2010. Parents in Prison and their Minor Children. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. A brief statistical portrait of incarcerated parents and their children.

Erving Goffman. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. A pathbreaking analysis of “total institutions” and the social life of mental patients.

Loïc Wacquant. 2010. “Class, Race & Hyperincarceration in Revanchist America,” Daedalus 139(3):74-90. Shows how U.S. punishment has been targeted by social class, race, and place, leading to the disproportionate incarceration of African American men from impoverished neighborhoods.

Comments 7

Tazima Jenkins Barnes — March 28, 2013

Enjoyed the read; though the content was disturbing to digest. The article painted a clear picture of the lives of those who have loved ones and family members in jail/prison. It made me think of a time when I attended the trail of George Jackson and Angela Davis members of the Black Panther Party in the early 1970's. I was a senior in High school. In order to get into the trail proceedings I was strip searched. They wanted to search my vagina and anus for "weapons and/or drugs. Thank God I was still a minor and that was prohibited at the time. I remember thinking this was a ploy by the 'system' as we use to call it back then; a ploy to keep the public from seeing that a fare and just process happened.

I remembered being humiliated by the search however non-the-less determined to not be turned away. Neither one of these people was family members but by political and social justice unity and commonalities they were my Brother and Sister in the struggle for justice- if you will.

Since that experience I often wonder if the incarcerated person really realizes what the person goes through to visit them. I am speaking not only of the physical challenges one goes through but the emotional and mental changes as well. As women where do we dump this anger and emotional stress? What do we tell our children? What do our children tell their friends?

The effect of incarceration on a family has huge affects that reaches beyond the point of incarceration but also once the person is released back into the community.

I look forward to reading more of Megan's work. Thank you Megan for the realization and public knowledge of the challenges of incarceration on the family and in relationships in general.

Deborah McIntosh — March 29, 2013

Thank you for writing this article.

I have had to deal with the things you describe, but as a mother instead of a spouse. I have had no one with whom I could share the ways these years have changed the dynamic of our family and of me. Reading your article helps me sort out and name those emotions and processes.

Being able to name them helps me to deal with how we have been changed by them, and maybe how we can overcome those affects some day.

Megan Comfort — April 3, 2013

Thank you very much Tazima and Deborah for your comments. I really appreciate you sharing your first-hand experiences with prison visiting and having an incarcerated loved one. Thank you also for expanding our thinking to mothers and other family members, politics and the post-Civil Rights era, and questions we need to be asking and ways we might move forward.

For people who have a loved one who is incarcerated and are looking for support, the Families and Corrections Network might be useful for you (http://fcnetwork.org/). Under their “resources” tab, you can access a Directory of Programs Serving Children and Families of the Incarcerated, which may be able to provide you with places to contact for support and other people with whom you can discuss your experiences. We welcome your comments and hearing your perspectives here as well.

Letta Page — April 26, 2013

UCLA's Marie E. Berry shares a great teaching exercise to work with this piece over in Teaching TSP: http://thesocietypages.org/teaching/2013/04/16/ripple-effects-of-incarceration/

Friday Roundup: Feb. 14, 2014 » The Editors' Desk — February 14, 2014

[…] “Repercussions of Incarceration on Close Relationships,” by Megan Comfort. How families must learn to love through the glass. […]

Francis Ssuubi — November 22, 2016

This a great article, Hope it can help to influence correction of the criminal justice system , world over. Francis Ssuubi

Coordinator- International Coalition for Children with incarcerated Parents!