Over on The Society Pages’ Cyborgology blog, Sarah Wanenchak writes about using images of amputee athletes in her Social Problems course. Check it out!

Over on The Society Pages’ Cyborgology blog, Sarah Wanenchak writes about using images of amputee athletes in her Social Problems course. Check it out!

This blog post, written by Lyndi Hewitt, originally appeared on the Mobilizing Ideas blog and appears here with the author and institute’s permission. We liked it so much we just had to share!

For those of us prescient enough (wink) to plan a social movements course for this semester, it’s been quite a ride. I’ve been teaching a first year seminar on global justice movements and, like many other instructors, altered my carefully planned syllabus in response to the unexpected wave of activism that emerged before our very eyes.

As the students in the course simultaneously processed core social movements scholarship and news coverage of the Occupy Wall Street protests, I was particularly struck by the fact that many students had very specific and often inaccurate ideas about who the protesters were (and what it cost them to be there) even after extensive, theoretically informed class discussion and news analysis. So I decided to invite the students to join me for a visit to Zuccotti Park. Newly equipped with social movements concepts, along with requisite iPhones and video cameras, the students and I ventured into the park on a chilly Saturday evening in early November. We observed a general assembly, discussed the various issues and frames represented among the signs, and interviewed protesters about their views. Despite the fact that most of the students were initially skeptical of Occupy Wall Street, they exhibited both intellectual curiosity and great respect for the protesters. One especially enthusiastic student prepared a short video documenting the protesters’ responses to his questions (which I share with his permission):

The two gentlemen featured prominently, both veterans, had a significant impact on the students. Their remarks around 5:50 encapsulate the disruption of students’ pre-existing assumptions: “I’m tremendously excited by what I see here. These people are extremely sophisticated people. They’re very intelligent people. They’re not bums. Don’t believe the media that we have nothing better to do, okay. We would like to be productive members of society. We were at one time and we would like to be again. We have a lot to contribute.”

Although we’d been discussing the Occupy Wall Street protests and applying social movement theories in the classroom for weeks, the experience of being in the park, seeing the encampment alongside the police, and talking with protesters proved to be a far richer learning opportunity for students. It blew the students’ minds that OWS protesters could be older, hard working, and patriotic; moreover, hearing movement grievances articulated face-to-face catalyzed a depth of understanding that wasn’t achievable simply through reading and watching video clips about those same grievances. Interestingly, our debriefing after the field trip revealed that over half the students had changed their opinions of the protesters as well as the legitimacy of the movement as a whole (all, it turned out, from an unfavorable to a more favorable opinion).

Seeing the OWS protesters through the eyes of my students reminded me how powerful a teacher experience is, and that more time spent in the midst of the action would be valuable for most of us.

A group of graduate students at the University of Minnesota put together these fantastic resources on teaching race, ethnicity, and migration.

The Global REM Teaching Modules are a set of teaching resources related to Global R(ace) E(thnicity) and M(igration). Modules are appropriate for use in high school classrooms, and introductory college-level courses. Each teaching module includes a brief introduction to the topic, source materials, discussion questions, and suggested readings. These modules provide busy instructors with a series of comprehensive and organized 50-minute lesson plans for facilitating learning related to global race, ethnicity, and migration. At the same time, they are flexible enough to provide instructors room to use the modules in ways appropriate to the particular aims of their own course themes.

The main objectives of the Global REM Teaching Modules:

- To improve students’ research skills by encouraging them to utilize and analyze a variety of source materials

- To increase use of source materials related to issues of race, ethnicity, and migration, particularly in a global and/or comparative context

- To foster interdisciplinary thinking and to incorporate a wide range of disciplinary perspectives and methods in the classroom

- To provide busy teaching assistants and instructors with ready-made lesson plans for 50-minute class periods. The modules are especially designed for teaching assistants and instructors who may not have an expertise in race, ethnicity, and migration but aim to augment discussion of global issues related to these topics

The teaching modules were developed by an interdisciplinary team of graduate students in 2007, and are maintained by the Institute for Global Studies and the Immigration History Research Center. If you have questions or comments about the teaching modules, you may direct them to outreach@umn.edu.

Below is guest post from Holly Kearny:

Social science is not new. It has been around for hundreds of years and is still being studied to this day. However, there were many founders of the science that looks at the non-natural world and into the elements of human behavior and beyond. Below, we have listed five of the most famous social scientists and their work.

- Auguste Comte – He was the first to coin the term “social science” in the nineteenth century. He was a French philosopher who believed in the concept of positivism, or that the collected senses made up all worthwhile information. He was also a prominent figure during the French Revolution in which he called for a doctrine based on science.

- Max Weber – This German was a sociologist and political economist who influenced many social scientists to come. He was one of the first to study methodological antipositivsm, or the belief that the findings that arise in social science cannot be fully interpreted by the scientific method and should focus on the meanings that social actions have.

- Karl Marx – He wasn’t just an advocate for workers or communism, Karl Marx was also a social scientist. Born in Germany, he came from a long line of rabbis. After his work brought controversy, he sought refuge in Belgium where he theorized that “the nature of individuals depends on the material conditions determining their production.” He would later join the Communist League and write the manifesto with Friedrich Engels, and it is still a hot topic of dispute today.

- Wiliam Du Bois – He proved that social sciences aren’t just for white men. Du Bois was born in 1868 in Massachusetts and was a stern advocate for civil rights. In his book “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade,” he even included an attack on civil rights leader Booker T. Washington for not doing more in the campaign for civil rights.

- Leon Festinger and James Carlsmith – A dual of social scientists took on an individual’s central stories and why they think and behave the way they do. The experiment was conducted in 1959 at Stanford University and involved students doing a boring task and then being paid to promote it. Expectations, outcomes, and more marked this amazing moment in social science history.

Holly Kearny manages the site www.becomingateacher.org. Her site helps students find the right college to get a teaching degree.

Here is a list of miscellaneous teaching resources that the graduate students at the University of Minnesota have compiled. We hope it’s helpful!

SOCNET: Sociology Courses and Curricular Resources Online – This website has links to all kinds of sociology courses, activities, syllabi, and other curricula online.

ASA Online Bookstore – Includes resources on teaching techniques, ASA Syllabi Sets, research briefs and volumes, social policy volumes, reference materials, national department information and management resources, and special journal issues and indexes (all for sale as hardcopies).

Reaching the Second Tier: Learning and Teaching Styles in College Science Education, by Richard Felder – This is an article about learning styles and how to teach students with different ways of understanding information.

Good Teaching: The Top Ten Requirements, Richard Leblanc – An article with tips for effective teaching.

Good Teaching Practices, Barbara Gross Davis – A compendium of classroom-tested strategies and suggestions designed to improve the teaching practices of all college instructors, including beginning, mid-career, and senior faculty members. The book describes 49 teaching tools that cover both traditional practical tasks–writing a course syllabus, delivering an effective lecture–as well as newer, broader concerns such as responding to diversity on campus and coping with budget constraints.

Teaching Effectiveness Program, University of Oregon – The Teaching Effectiveness Program provides a wide range and variety of valuable resources for instructors. Among the materials included in this section are general classroom resources, information focusing on diversity, articles about featured University of Oregon teachers, library listings, and web links.

Good Teaching Ideas from the University of Oregon – This site is from the University of Oregon’s Teaching Effectiveness Program. It has links and ideas for group learning, teaching large classes, service learning, and creating a teaching portfolio.

Teaching through Distance Education: An article from Cause/Effect teaching journal – This article, “An Emerging Set of Guiding Principles and Practices for the Design and Development of Distance Education Combining Good Teaching with Good Technology”, is an excellent resource for faculty and instructors considering this option and/or using WebCT.

The Nine and a Half Commandments of Good Teaching – In addition to the nine and a half commandments of good teaching, this site has articles and advice on lectures, teaching methods, and classroom management.

Working Conceptualization of ‘Good Teaching’ Introduction – This article is an attempt to define good teaching. It focuses on beliefs and dispositions, the importance of professional and political knowledge, and good teaching practices and skills.

Inside the Mystery of Good Teaching – This article also focuses on good teaching and closing the performance gap, and the resources available to teachers in their path to good teaching.

WebCT Tools and the Good Teaching Principles They Support – This site outlines the tools available through WebCT and the learning and interaction goals they help students and instructors meet.

Teaching Tips Index – This useful index includes information and articles about learning styles, motivating students, course design, dealing with difficult students and behavior, the first day of class, assessment techniques, lesson plans, syllabus design, and much more.

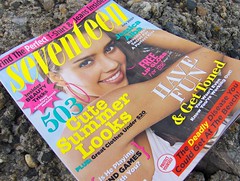

Magazines geared towards teens are some of the best examples of illustrating gender norms for students new to Sociology. We recommend this activity for an Intro to Sociology class or to begin a course on the Sociology of Gender:

Have students read “Selling Feminism, Consuming Femininity” by Amanda M. Gengler in the Spring 2011 issue of Contexts. Then, have them look through magazines aimed at young women or men (print or online) with a new eye for spotting the underlying messages about femininity and masculinity contained in the images or articles.

Send them home with a worksheet with these questions repeated 4-6 times so they can answer them about each image/article they find:

1. What message does this image/article portray about femininity or masculinity?

2. Do you believe this message has the potential to be harmful to young men or women? If so, in what ways? If not, why not?

3. Imagine you are talking to your younger brother/sister/cousin/daughter/son about this image or article, what would you say?

Have them bring their examples into class and form small groups for a “Gender Workshop” (this could definitely work in a large class!) They’ll take turns describing their finds to the other members of the group. After they’ve all had their turn, they’ll have a guided discussion about their experience, addressing these questions in a small group discussion:

1. What was this experience like for you? Was there anything surprising about looking at these magazines in this way?

2. Do you believe that absorbing gender norms like the ones discussed today could have negative consequences for young men and women? If so, how?

Give examples:3. Whose responsibility is it to manage such messages about gender norms? The publishers of the magazines? The authors of the articles? The advertisers? The parents of the teens? The teens themselves?

Many instructors wonder if they are teaching concepts students can actually apply in their daily lives outside of the classroom. Chris Uggen, a professor at the University of Minnesota, decided to find out through a bonus question on the final exam in his sociology of deviance course. Specifically, he asked students to provide particular examples of how they used class material outside of the course sometime during the semester. And, he received good news–students shared many ways in which they used course material. To view them and view more of his reflections on this simple but powerful idea, see his blog here.

Rebecca Tiger’s culture review “They Tried to Make Her Go to Rehab” (about the reaction to Lindsay Lohan’s struggles with drugs and alcohol) would be useful in any deviancy course or for organizing a discussion on addiction discourses or media/online interaction.

We recommend having the students read the article and then conducting their own review of comments about celebrity addiction that they can find online (like Rebecca Tiger’s review of Perez Hilton’s coverage). Have them bring examples of what they find to class to get a discussion going on how celebrity addiction is portrayed and how these discourses relates to drug policy and rehabilitation for the rest of us.

You could also bring up Amy Winehouse, whose recent death reinvigorated the public discussion of the causes, cures, and consequences of addiction.

When I took my first sociology course my freshman year of undergrad, I had no idea I would enjoy it more than the biology courses I was taking for my major. But, I loved it. In fact, I can still remember the simple classroom activity that caused me to rethink my major.

Our professor asked us to visit a toy store (or a store with a fairly sizeable toy section) and write a short reflection paper about the differences we saw between toys marketed for boys and toys marketed for girls. She asked us to pay attention to the packaging (What types of colors are used? Who is depicted playing with the toys?) and the toys themselves. Afterward, students discussed their findings in class, and it was clear that many of the students really enjoyed the activity. We then discussed gender and gender socialization, and even though I don’t study gender, the way sociologists examine what most people take for granted had me hooked.

Students love to analyze popular culture because it allows them to think about and write about the music, movies, TV shows, or books that they already love (or love to hate!) A fun way to use popular culture in the classroom is to have your students re-examine one of their favorite shows, movies, albums, etc. from a sociological perspective.

We recommend using Rebecca Hayes-Smith’s book review “Gender Norms in the Twilight Series” as a guide for your students (from the Spring 2011 issue of Contexts). Have your students read and discuss this short review and then go out and write one of their own!