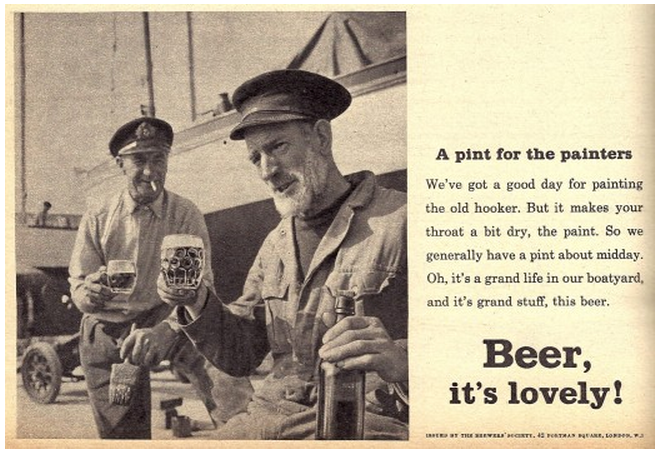

Here we have another great vintage ad (1962) that upsets the idea that today’s norms are trans-historical. First, the idea of having a “pint about midday” would be considered inappropriate by many U.S. employers (though, as several commenters have pointed out, not necessarily elsewhere). Second, the large print — “Beer, It’s Lovely!” — sounds unmasculine today, even though these grizzled sea-farers likely would have seemed perfectly masculine enough at the time.

From the RAF Flying Review, found at Retronaut.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.