Cross-posted at Jezebel.

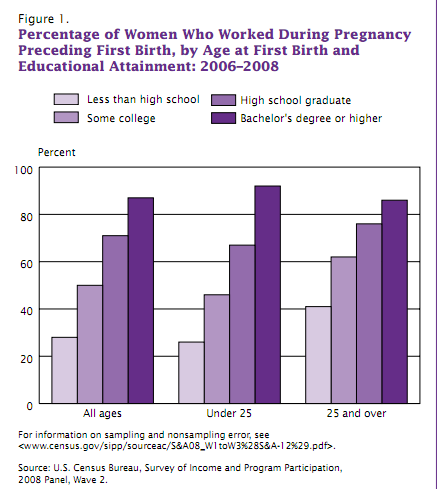

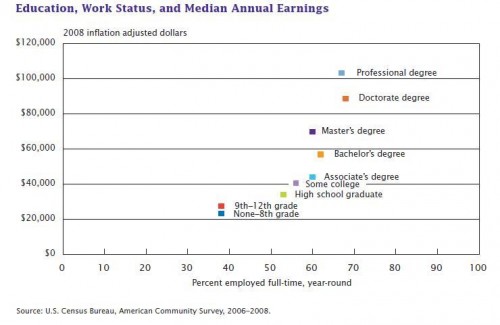

The U.S. Census Bureau recently released a report on employment and parental leave for first-time mothers. The mean age at first birth is now 25 years. And while a few decades ago the norm was for women to quit work upon getting pregnant, from 2006 to 2008, 56.1% of women worked full time during their pregnancy, leaving work only as the due date approaches. However, this varies widely by educational level, largely because women with the lowest levels of education are less likely to be working regardless:

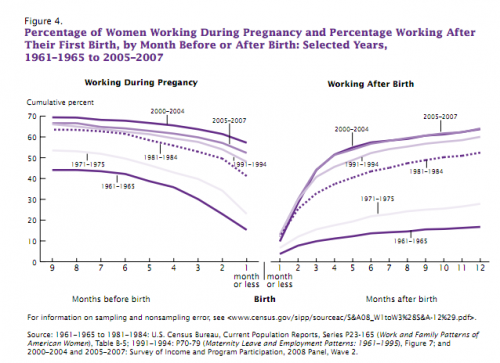

The graph on the left below shows how many months before the birth working women left their work; the graph on the left shows how many months after the birth they returned. As we see, over time women have stayed at their paid jobs longer and returned more quickly:

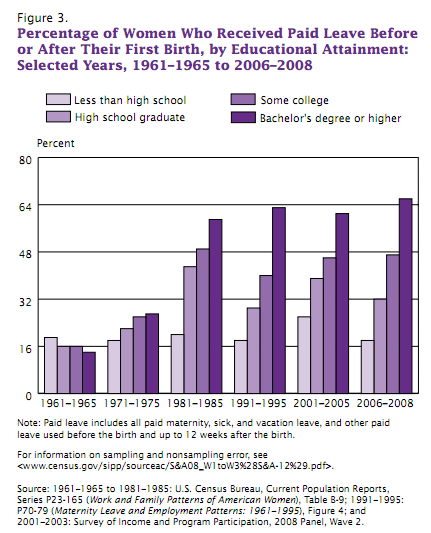

During the 2006-2008 reporting period, for the first time a majority — but a bare one, at 50.8% — of first-time mothers in the labor force used paid leave (maternity leave, sick days, etc.). Not surprisingly, access to paid leave also varied greatly by educational level, and that gap has widened significantly over time:

So nearly half of first-time mothers in the U.S. still do not have paid leave from their jobs.

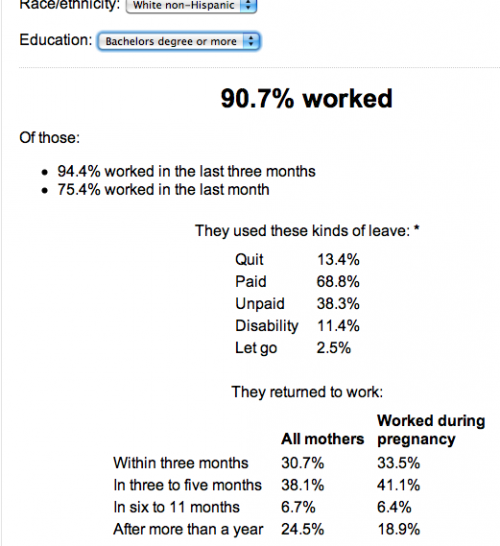

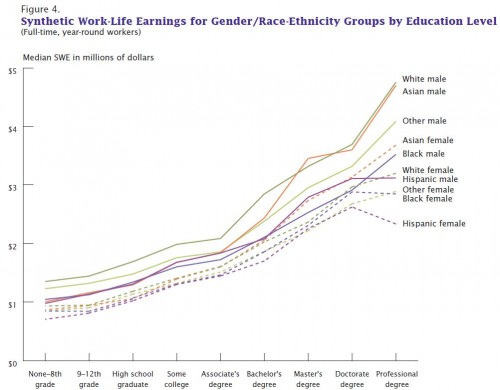

PBS created an interactive program based on the data that allows you to see the patterns more clearly. You select a race/ethnicity and educational level and get a detailed breakdown of the data. For instance, here’s the info for White non-Hispanic women with a 4-year college degree or higher: