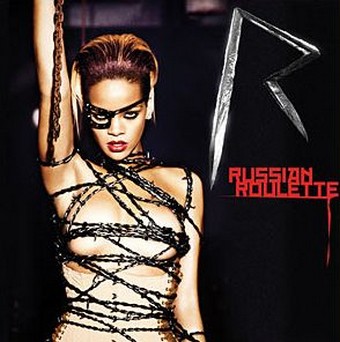

Rihanna’s first new single since getting beaten by boyfriend Chris Brown is titled “Russian Roulette.” On the cover, she is wrapped in barbed wire with an eye patch that looks like a black eye:

The lyrics include:

And you can see my heart beating

You can see it through my chest

And I’m terrified but I’m not leaving

Know that I must pass this test

So just pull the trigger

And:

So many won’t get the chance to say goodbye

But it’s too late too pick up the value of my life

Given the many, many young girls that blamed Rihanna for her beating, releasing a song that posits that love is simply dangerous is really… disappointing.”

You can read a more thoughtful discussion about this by Anna North at Jezebel.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

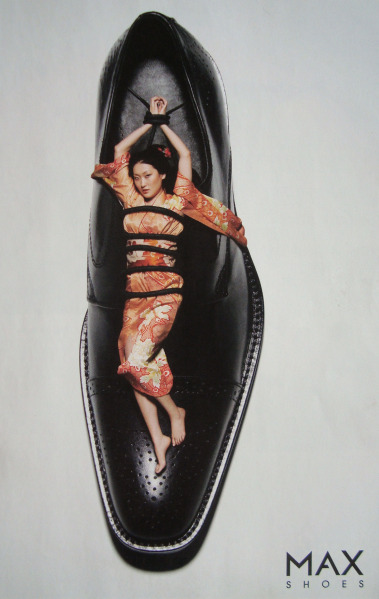

Both via Copyranter (

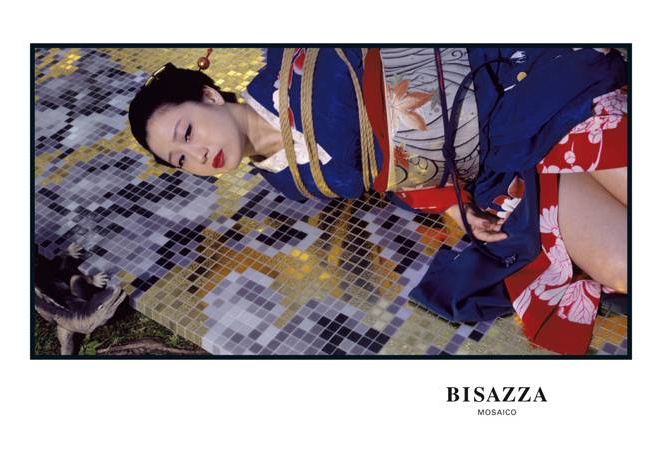

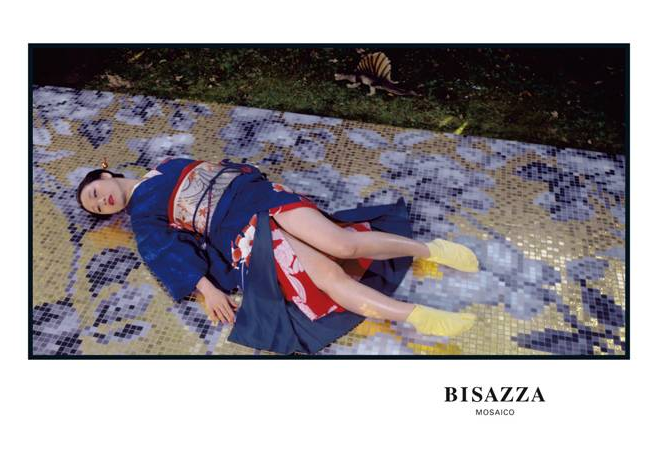

Both via Copyranter (