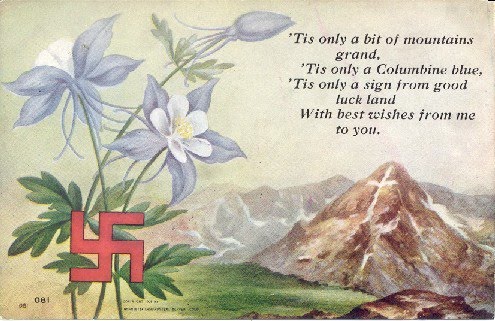

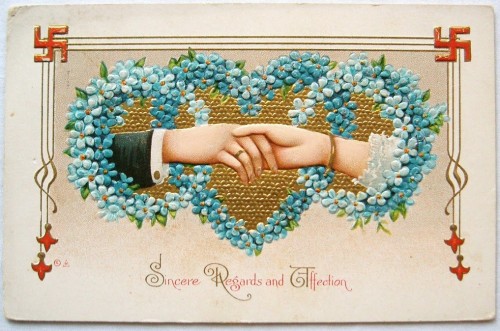

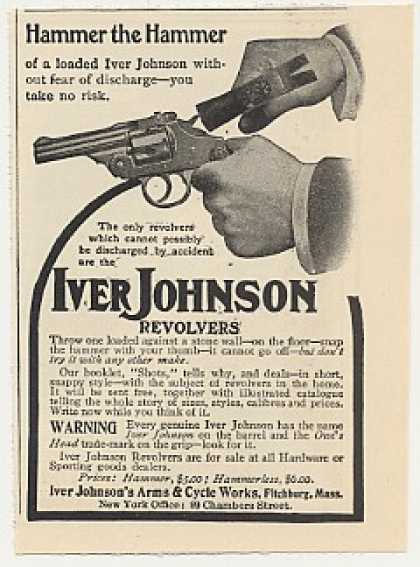

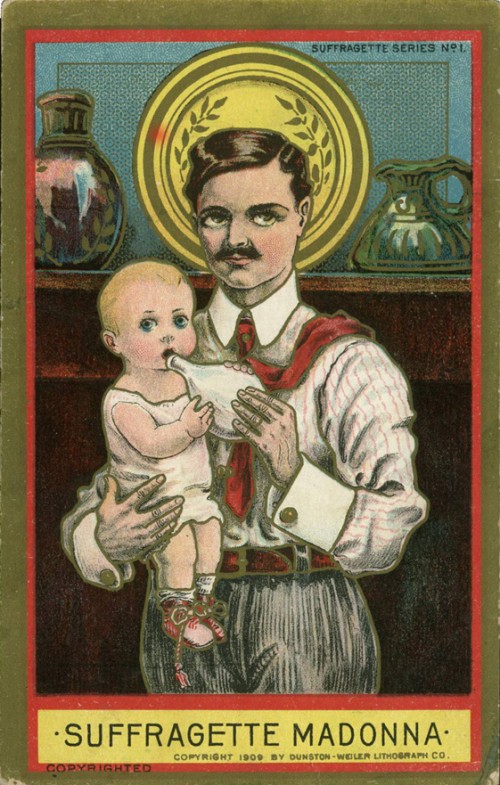

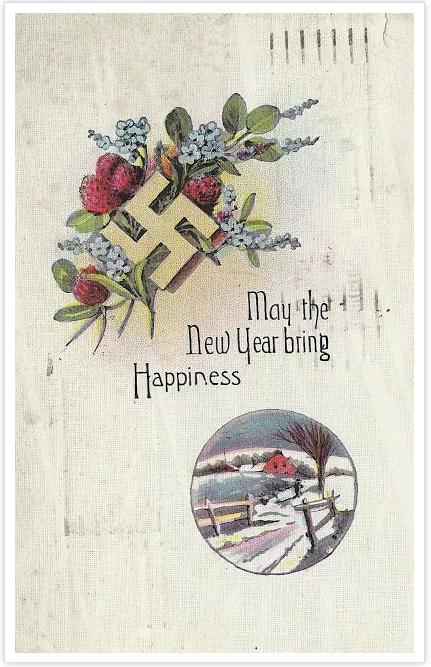

It’s a little known fact that the swastika, famously appropriated and perverted by the Nazis, is (or was) a symbol of good luck. Dating back to the Neolithic period, the symbol was frequently included in greetings and used as decoration. A 1917 ad for swastika jewelry, for example, called the symbol the “oldest cross” and explained it like this: “To the wearer of swastika will come from the four winds of heaven good luck, long life and prosperity.”

It’s a little known fact that the swastika, famously appropriated and perverted by the Nazis, is (or was) a symbol of good luck. Dating back to the Neolithic period, the symbol was frequently included in greetings and used as decoration. A 1917 ad for swastika jewelry, for example, called the symbol the “oldest cross” and explained it like this: “To the wearer of swastika will come from the four winds of heaven good luck, long life and prosperity.”

Here are some additional examples of the swastika being used to send hopeful messages to loved ones, found by Tom Megginson at The Ethical Adman along with the one above:

Happy New Year, everyone.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.