Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

In the third stall at a women’s room at the University of Western Ontario, someone had written, “What was the worst day of your life?”

A few responses were humorous, but most were serious.

- Every day, struggling with an eating disorder.

- The day I found out my father was an alcoholic.

- The day I was raped.

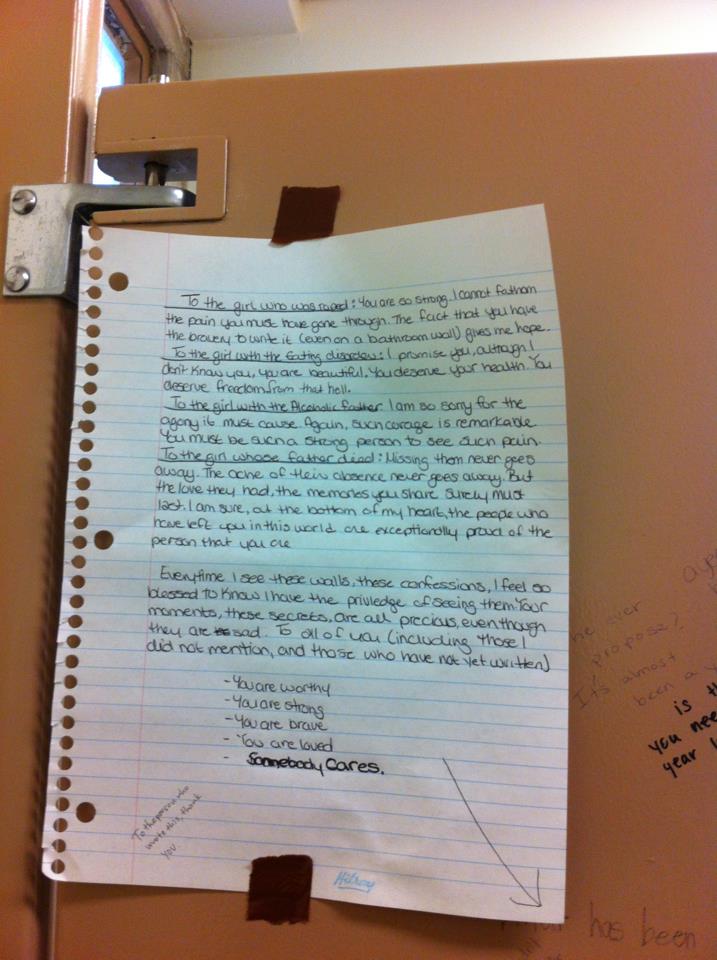

One student who saw these took a piece of notebook paper, wrote a sympathetic response to each, and taped it on the wall of the stall (transcript follows):

Transcript (borrowed from The Huffington Post):

To the girl who was raped: You are so strong. I cannot fathom the pain you must have gone through. The fact that you have the bravery to write it (even on a bathroom wall) gives me hope.

To the girl with eating disorders: I promise you, although I don’t know you, you are beautiful, you deserve your health. You deserve freedom from that hell.

To the girl with the alcoholic father: I am so sorry for the agony it must cause. Again, such courage is remarkable you must be such a strong person to see such pain.

To the girl whose father died: Missing them never goes away. The ache of their absence never goes away. But the love they had, the memories you share surely must last. I am sure, out of the bottom of my heart, the people who have left you in this world are exceptionally proud of the person you are.

Everytime(sic) I see these walls, these confessions, I feel so blessed to know I have the priviledge(sic) of seeing them. Your moments, these secrets, are all precious even though they are sad. To all of you (including those I did not mention, and those who have not yet written)

-You are worthy.

-You are strong.

-You are brave.

-You are loved.

-Somebody cares.

It went viral. Reddit picked it up, and the story has been in Canadian newspapers. But this example is not so unusual. A study of bathroom graffiti at a New Zealand university (unfortunately behind a paywall) found similar themes:

…inscriptions in the women’s toilets were talking about love and romance, soliciting personal advice on health issues and relationships, and discussing what exact act constitutes rape. Women also tried to placate more heated discussions (e.g., “Stop this. There is no reason to say these things. Why so much in-fighting?”).

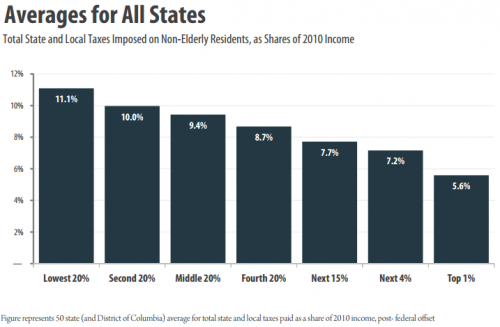

The men wrote about politics and money (especially taxes and tuition). Men also posted insults that were far more numerous and aggressive than those in the women’s room. Only the men wrote racist graffiti.

Drier’s note, then, is a nice example of a documented trend: anonymous women being nice to each other in their bathrooms.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.