We’re celebrating the end of the year with our most popular posts from 2013, plus a few of our favorites tossed in. Enjoy!

Hip-hop music is frequently described as violent and anti-law enforcement, with the implication that its artists glorify criminality. A new content analysis subtitled “Hip-Hop Artists’ Perceptions of Criminal Justice“, by criminologists Kevin Steinmetz and Howard Henderson, challenge this conclusion.

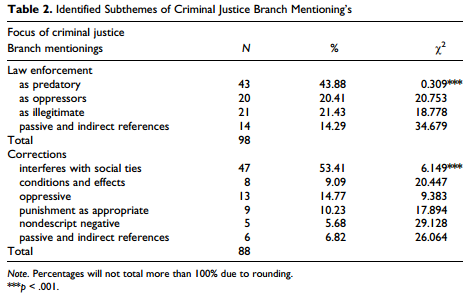

After an analysis of a random sample of hip-hop songs released on platinum-selling albums between 2000 and 2010, Steinmetz and Henderson concluded that the main law enforcement-related themes in hip-hop are not pleasure and pride in aggressive and criminal acts, but the unfairness of the criminal justice system and the powerlessness felt by those targeted by it.

Lyrics about law enforcement, for example, frequently portrayed cops as predators exercising an illegitimate power. Imprisonment, likewise, was blamed for weakening familial and community relationships and described a modern method of oppression.

Their analysis refutes the idea that hip-hop performers are embracing negative stereotypes of African American men in order to sell albums. Instead, it suggests that the genre retains the politicized messages that it was born with.

Steinmetz and Henderson offer Tupac’s “Crooked Nigga Too” (2004) as an example of a rap that emphasizes how urban Black men are treated unfairly by police.

Yo, why I got beef with police?Ain’t that a bitch that motherfuckers got a beef with meThey make it hard for me to sleepI wake up at the slightest peep, and my sheets are three feet deep.

The authors explain:

Police action perceived as hostile and unfair engenders an equally hostile and indignant response from Tupac, indicating a tremendous amount of disrespect for the police.

Likewise, Jay-Z, in “Pray” (2007), raps about cops who keep drugs confiscated from a dealer, emphasizing a “power dynamic in which the dealer was unfairly taken advantage of but was unable to seek redress”:

The same BM [‘‘big mover’’—a drug dealer] is pulled over by the boys dressed bluethey had their guns drawn screaming, “just move or is there something else you suggest we can do?”He made his way to the trunkopened it like, “huh?”A treasure chest was removedcops said he’ll be back next monthwhat we call corrupt, he calls payin’ dues

Henderson offers Jay-Z’s “Minority Report” as a great overall example.

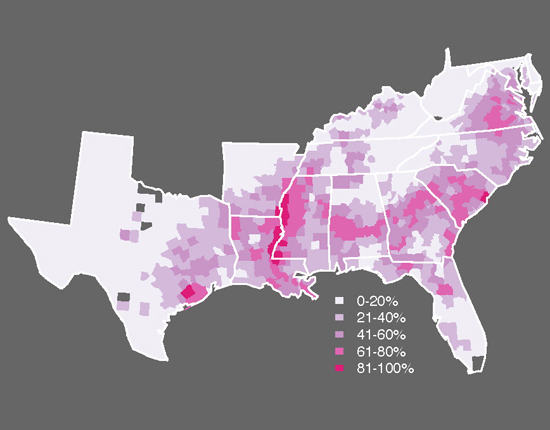

Of course, the rappers — in their collective wisdom — are absolutely correct to suspect that the treatment that their communities receive from the police, corrections, and courts are unfair. People of African descent are routinely targeted by police (see the examples of New York City and Toronto), even though racial profiling doesn’t work; Blacks are are more likely to be arrested and sentenced than Whites, regardless of actual crime rates; schools and juvenile detention systems are increasingly intertwined in inner cities; imprisonment tears families apart, disproportionately harming families of color; and even Black children don’t trust the police.

Steinmetz and Henderson conclude:

We actually found that the overwhelming message in hip-hop wasn’t that the rappers disliked the idea of justice, but they disliked the way it was being implemented.

These communities, then, have a strong sense of justice… rooted in the sense that they’re not getting any.

Cross-posted at Racialicious and PolicyMic.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.