I spent the last few days in Savannah, Georgia at the winter meeting of Sociologists for Women in Society. I’m from Maine and didn’t travel much in the U.S. as a child. It wasn’t until I was 27 that I ventured south of Washington, D.C. The history of slavery is something that I’ve always wanted to learn more about.

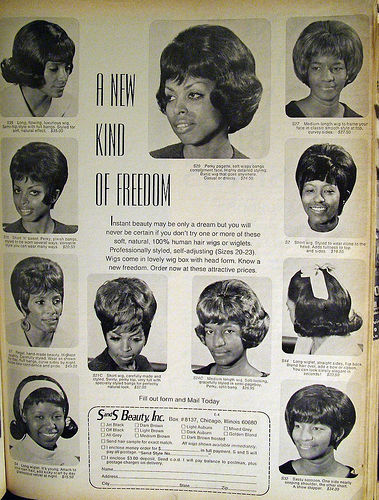

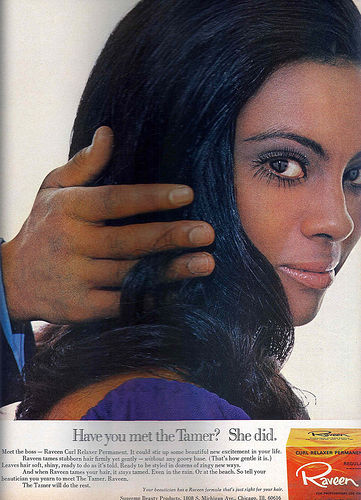

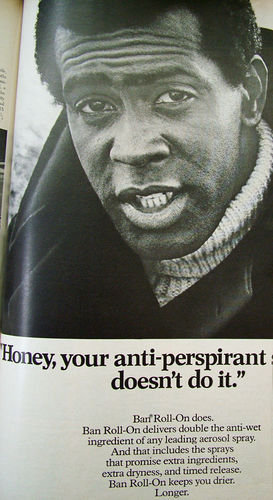

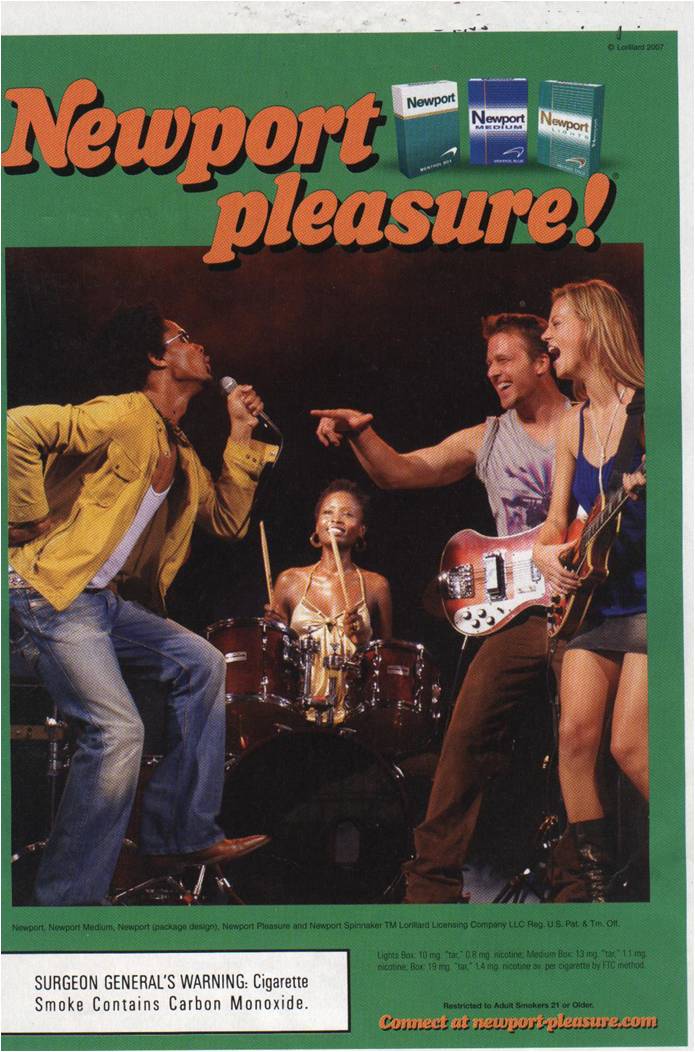

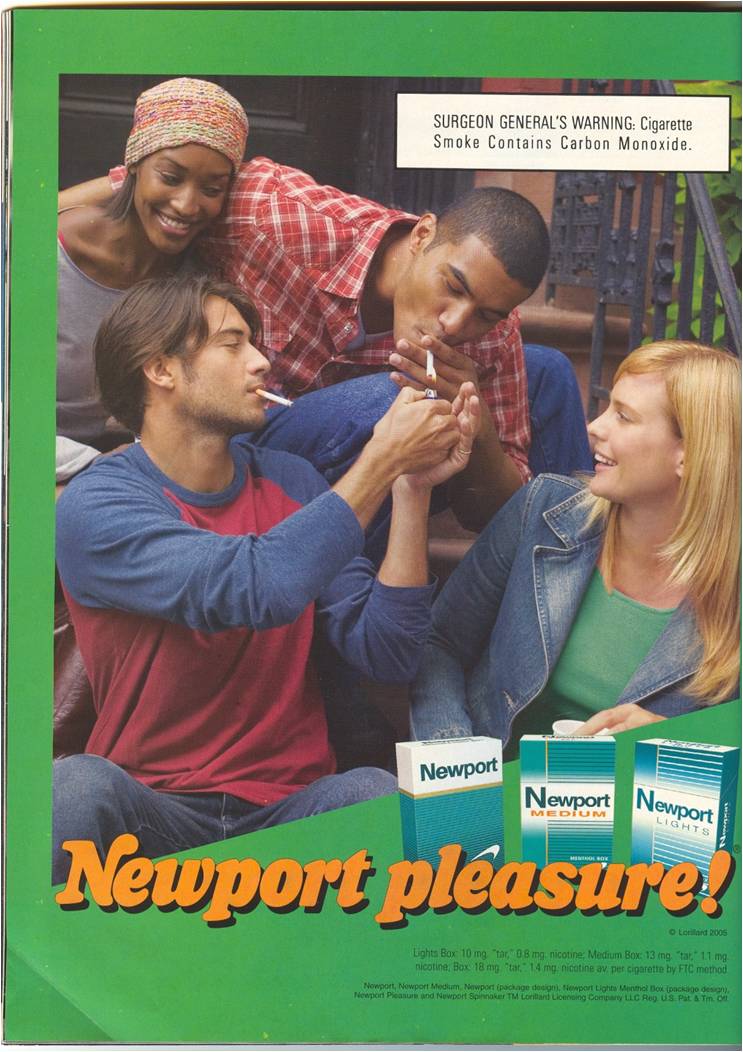

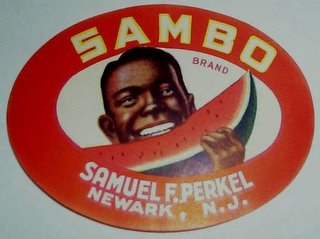

After spending a day at the Civil Rights Museum and touring the historic First African Baptist Church, I was stunned to find these items for sale in nearly every tourist souvenir shop.

These make me uncomfortable. They’re caricatures of Black women without any kind of historical context. Like Gwen in this post, I have less of a hard time with old, historic artifacts (like the antiques pictured below that I found at a flea market). But, I do think they belong in a museum alongside other historic artifacts and information.

But, newly made, currently produced reproductions of Black women slaves, as salt shakers and magnets? How is that alright? To me this is almost as creepy as if they were selling Klu Klux Klan robe magnets. Is it that as a Northerner I’m more uncomfortable around issues of slavery, than, say, a Southerner would be? I feel a similiar way when I see confederate flags outside of their historical context– and there were plenty those for sale in tourist stores as well. I’d love to hear thoughts on this use of racist “history” for marketing and tourism in a city like Savannah that is filled with history of slave trade and segregation.