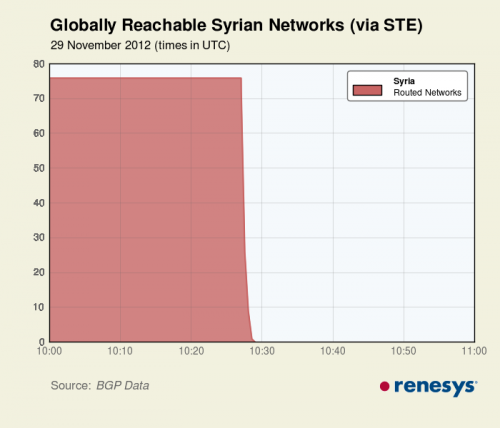

Two days after 6 adults and 20 elementary school children were shot and killed in Newtown, CT, the Miami Herald homepage looked like this:

On the left side of this screenshot, the Herald shows images of the dead and notes how “America mourns” their loss. At right, one of their five-or-so rotating advertisements shows a large handgun and links to a website for the U.S. Concealed Carry Association, a company that sells – among other things – strategies to quickly arrange for conceal carry permits in your state.

The company’s tagline: “Knowledge is your best weapon. Preparation is your best defense.” Apparently, to a segment of the population this visual coupling advertisement read something like, “Mourn for now. Lock and load for next time.”

That such a provocative advertisement would appear in close proximity to a sensitive news story is unlikely to be accidental. News outlets are quite smart about what they post – and where – both in terms of news products and paid content.

But this juxtaposition of weaponry and those who have died from such products represents more than a short-term economic choice. Instead, it reflects the fact that we live in a culture that strongly supports gun ownership and loose gun control laws. Had the newspaper thought that such an advertisement — published at this particular time and in this particular way — would ostracize their audience or advertisers, they wouldn’t have run it.

Some call the media the “fourth estate” – an institution that, alongside the courts, the oval office, and congress, keeps our country in balance. The juxtaposition in that screenshot, however, calls into question this role for the traditional media. Instead, they are simply reflecting the status quo, one largely controlled by those who are already in power. If this is the case, we can’t count on the media to check the power elite. Any real change, then, is going to come from collective action and alternative media.

—————————

Robert Gutsche Jr. is an assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Florida International University. His research deals with the sociology of news and news as a cultural artifact.