Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

While newspapers give a lot of ink to arguments about whether reducing the budget deficit will boost or reduce growth, they seem to have little interest in the related issue of whether economic growth really benefits the great majority.

David Cay Johnston, the Pulitzer Prize winning financial journalist, recently addressed this issue drawing on the work of economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty:

In 2011 entry into the top 10 percent… required an adjusted gross income of at least $110,651. The top 1 percent started at $366,623.

The top 1 percent enjoyed 81 percent of all the increased income since 2009. Just over half of the gains went to the top one-tenth of 1 percent, and 39 percent of the gains went to the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent.

Ponder that last fact for a moment — the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent, those making at least $7.97 million in 2011, enjoyed 39 percent of all the income gains in America.

So, 81 percent of all the new income generated from 2009 to 2011 was captured by the top 1 percent income earners, where income is defined as adjusted gross income, which refers to income minus deductions or taxable income. In other words, growth, even accelerated growth, is not going to do the majority much good if the economic structure remains the same.

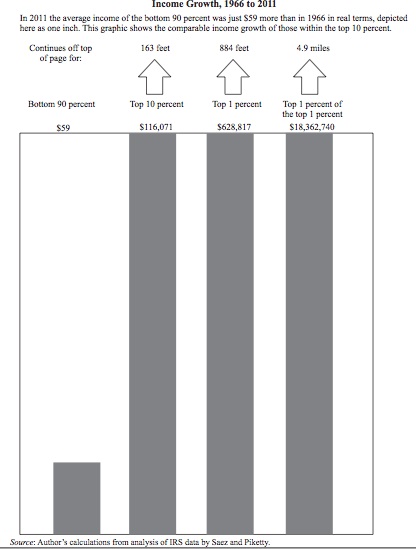

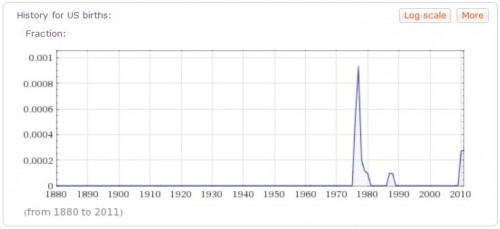

Johnston highlights the problem with our existing economic model with perhaps an even more shocking example. He compares the average income growth of the bottom 90 percent with the average income growth of the top 10 percent, 1 percent, and top 1 percent of the top 1 percent over the period 1966 to 2011.

It turns out that the average income of the bottom 90 percent rose by a miniscule $59 over the period (as measured in 2011 dollars). By comparison, the average income of the top 10 percent rose by $116,071, the average income of the top 1 percent rose by $628,817, and the average income of the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent increased by a whopping $18,362,740. In short, growth alone means little if the great majority of people are structurally excluded from the benefits.

In an effort to highlight this extreme disparity in adjusted income growth rates, Johnston suggests plotting the numbers on a chart, with $59, the amount gained by the bottom 90 percent, represented by a bar one inch high. As the chart below shows, the bar representing average gains for the top 10 percent would be 163 feet high, that for the top 1 percent would be 884 feet high, and that for the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent would be 4.9 miles high.

In sum, the real challenge facing the great majority of Americans is not figuring out how to make the economy growth faster. Rather, it is figuring out how to create space for a real debate about how to transform our economy so that growth will actually satisfy majority needs.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.