Originally posted at Orgtheory.

So there are a thousand reasons Trump won the election, right? There’s race, there’s class, there’s gender. There’s Clinton as a candidate, and Trump as a candidate, the changing media environment, the changing economic environment, and the nature of the primary fields. It’s not either-or, it’s all of the above.

But Josh Pacewicz’s new book, Partisans and Partners: The Politics of the Post-Keynesian Society, implies a really interesting explanation for the swing voters in the Rust Belt—the folks who went Obama in 2008, and maybe 2012, but Trump in 2016. These voters may make up a relatively small fraction of the total, but they were key to this election.

Pacewicz’s book, which just came out this month, doesn’t mention Trump, and presumably went to press long before Trump was even the presumptive Republican nominee. And the dynamics Pacewicz identifies didn’t predict a specific outcome. (In fact, Josh guest-blogged at orgtheory in August, but focused on explaining party polarization, and did not venture to predict a winner.)

But Partisans and Partners nevertheless does a really good job of explaining what just happened. Its argument is complex, and doesn’t imply a lot of obvious leverage points for decreasing political polarization or the desire for “disruptive” candidates. But I think it’s an important explanation nonetheless.

The book is based on ethnographic and interview data collected over a period of several years in two Rust-Belt Iowa cities of similar size, one traditionally Republican, and the other traditionally Democratic. Both of these cities saw a transformation in their politics in the 1980s. Until the 1970s, urban politics were organized around a partisan divide closely associated with local business elites, on the Republican side, and union leaders, on the Democratic side. Politics was highly oppositional, and the party that won local elections got to distribute a lot of spoils. But it was not polarized in the sense it is today—while there were fundamental differences between the parties, particularly on economic issues, positions on social issues were less rigidly defined.

During the 1980s, something changed. Pacewicz calls that something “neoliberal reforms”; I might argue that those are just one piece of a bigger economic transformation that was happening. But either way, the political environment shifted. Regulatory changes encouraged corporate mergers and buyouts. This put control of local industry in distant cities and hollowed out both business elites and union power. The federal government shifted from simply handing cities pots of money that the party in power could control, to requiring cities to compete for funds, putting together applications that would compete with those of other cities. This environmental change facilitated the decline of the old “partisans”—the business and labor elites—and the rise of a new group of local power brokers—the “partners”.

The partners were more technocratic and pragmatic. They did not have strong party allegiances, nor did they see politics as being fundamentally about competition between the incompatible interests of business and labor. Instead, they focused on building temporary alliances among diverse groups with often-conflicting interests. Think business-labor roundtables, public-private partnerships, and the like. This is what was needed to attract industry from other places (look how smooth our labor relations are!) and to compete for federal grants and incentives (cities with obviously oppositional politics tended to lose out). The end of politics. Sounds great, right?

The problem was that these dynamics also hollowed out local parties. The old partisans had lost power. Partners didn’t want to be active in party politics. This left parties to activists, who over time came to represent increasingly extreme positions—a new wave of partisans.

What did this mean for the average voter? Pacewicz shows how older voters still conceptualized the two parties as fundamentally reflecting a business/labor divide. But most younger voters came to understand politics as representing a divide between partners—people working together, setting aside differences, for the benefit of the community—and partisans—people representing the interests of particular groups.

Partners didn’t like politics. They didn’t really think it should exist. They disliked political polarization, thought that people were pretty similar underneath their surface differences, and that conflict was generally avoidable. They distrusted politics, their party affiliation tended to be provisional, and they often responded only to negative ads around hot-button issues.

The new partisans, on the other hand, were alienated from contemporary life. They thought things were going to hell in a handbasket. They were looking for change, and saw outsider candidates as appealing—candidates who promised to shake up the system. Many had a strong preference for Democrats or Republicans. But while for traditional voters party affiliation was rooted in a sense of positive commitment, for the new partisans, it was based on disaffection with the alternative. And a key group of “partisans” was politically uncommitted (a contradiction in terms?)—disaffected and angry and wanting politics to solve their problems, but not aligned with a party.

The 2008 election illustrates how these types respond to candidates. In the primaries, partners liked Obama, responding well to his post-partisan image. He was less favored by Democrats and traditional voters and partisans. By fall, though, traditional (Democratic) voters and (Democratic) partisans tended to get on board, while partners waffled as Obama came to seem more partisan.

The most erratic group was the uncommitted partisans. These people wanted somebody—anybody—to shake things up, to change the system. And they wanted somebody to represent them—the outsider. They tended to lean toward GOP candidates (one illustrative voter was a big Palin fan), but many also simply remained disaffected and stayed home.

This is the group, it seems to me, that is key to understanding the 2016 election. Democrats gonna Democrat, and Republicans gonna Republican. In the end, most people really aren’t swing voters. But the unaffiliated partisans are the type of voters who would have found some appeal in both Bernie and Trump: someone claiming to represent the everyman, and someone willing to shake up the status quo.

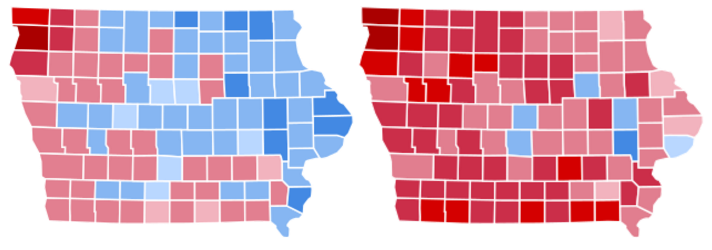

In the end, these folks are unlikely to be motivated to vote for a Clinton or a Romney. It’s just more of the same. But they can be energized by populism, and by the outsider. These are the people who will vote for Trump just as a big old middle finger to the system. Partisans and Partners isn’t specifically trying to explain Trump’s win, in Iowa or anywhere else. But it does as good a job as anything I’ve read at pointing in the direction we should be looking.

Elizabeth Popp Berman, PhD is an associate professor of sociology at the University at Albany, SUNY, and the author of the award-winning book Creating the Market University: How Academic Science Became an Economic Engine.