Yesterday Native Appropriations featured a presentation about Urban Outfitters, cultural appropriation in fashion, and the struggle to get the clothing chain to stop labeling clothing as “Navajo.” The presentation is great both for explaining this particular case — which included the Navajo nation sending a cease-and-desist letter demanding that Urban Outfitters stop using the term Navajo in its marketing — and also because it shows how one particular story spread through social media, which increasingly have the ability to bring mainstream media attention to stories that otherwise might have gone unnoticed.

science/technology: internet

Hennessy Youngman is one of things-on-the-internetz that validates the entire enterprise. In the fast and fascinating 10 minute clip here, Youngman traces the history of performance art, linking it to Occupy and our contemporary engagement with the internet. Oh, and totally worth watching to the end.

Hennessy Youngman is one of things-on-the-internetz that validates the entire enterprise. In the fast and fascinating 10 minute clip here, Youngman traces the history of performance art, linking it to Occupy and our contemporary engagement with the internet. Oh, and totally worth watching to the end.

(Hennessy, if you’re reading, I was the one that tweeted at you to do a video about The Levitated Mass. Nobody could do it quite like you! PS – whisky is my drink too.)

Also from Hennessy Youngman:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Dominant groups have the power to control representations of less-powerful groups. They exert an out-of-proportion influence on their cultural portrayals.

Dominant groups have the power to control representations of less-powerful groups. They exert an out-of-proportion influence on their cultural portrayals.

We’ve previously featured objections to simplistic portrayals of the enormous continent of Africa, especially as a place that is primitive and hopelessly burdened by death, disease, poverty, corruption, and other problems. Chimamanda Adichie, for example, objects to the “single story of Africa” and Binyavanga Wainaina tell us how not to write about Africa. Elsewhere, we’ve illustrated how the bustling city of Nairobi is portrayed as a savanna with giraffes and elephants.

An organization called Mama Hope, sent in by Jennifer C., seeks to challenge this perception. They want the world to think of Africa as a place of hope and possibility. To this end, Mama Hope is producing videos that “…feature the shared traits that make us all human— the dancing, the singing, the laughter…” They look like this:

The effort reminds me of the “Smiling Indians” and “More Than That” videos, sent in by Katrin and Anna W. The first addressed the stereotype of the “stoic Indian,” while the second is designed to counterbalance the common portrayal of reservations as miserable places full of one-dimensional hopeless people (something we are certainly sometimes guilty of).

Smiling Indians:

More Than That…:

These videos are examples of the way that the democratizing power of new technologies (both the internet in general and the relatively easy ability to take video and edit) are offering marginalized peoples an opportunity to contest representations by dominant groups.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Cross-posted at Compassionate Societies.

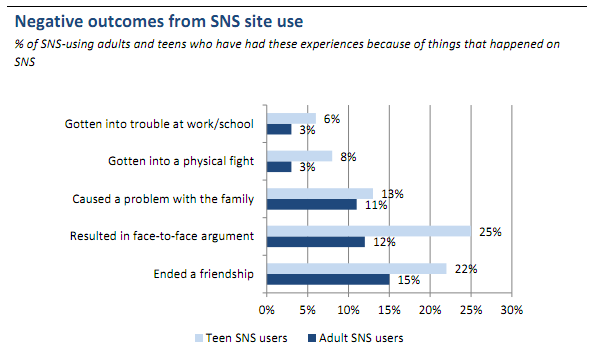

A new study from Pew, based upon a large national survey, found that people reported a lot more cruelty and the absence of kindness that many would expect. This implies that social networking sites (SNS) could use a lot more compassion.

Among adults, 85% say that their experience on the sites is that people are mostly kind. Fewer teens said the same, only 69%. More, social networking sites contributed to real life problems: including arguments and physical fights with friends, family members, teachers, or co-workers. In all categories, teens were about twice as likely to report that SNS got them into trouble:

Racial minority populations encountered an even more cruel environment on SNS. Forty-two percent of Black and 33% of Hispanic SNS users said they frequently or sometimes saw language, images, or humor that they found offensive, compared with 22% of White SNS users.

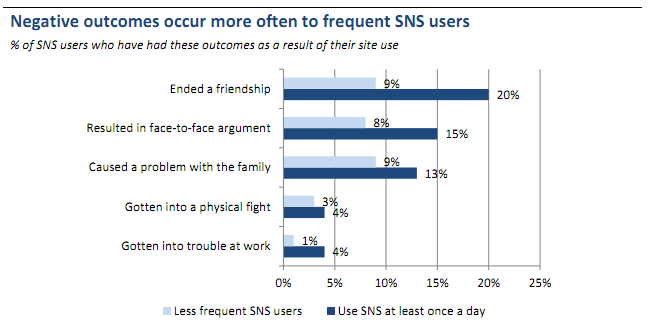

Interestingly, people who used social networking sites on a daily basis were far more likely to report experiencing negative things:

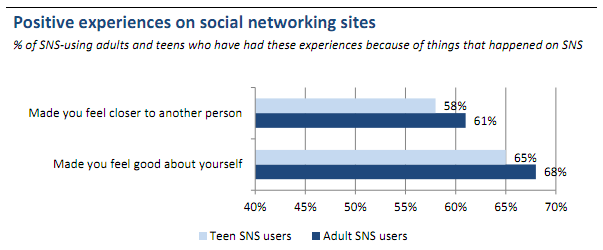

SNS users also reported positive experiences, suggesting that, for many, social networking is a mixed bag of good and bad:

————————

Ron Anderson, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota, has written many books and hundreds of articles, mostly on technology. In his retirement, he is doing research and writing on compassion and suffering and maintains the website CompassionateSocieties.org.

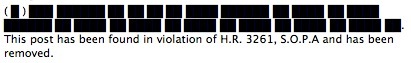

Last Wednesday, January 20 18, over 7000 websites participated in a massive protest opposing bills H.R. 3261, the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and S. 968, the PROTECT IP Act (PIPA). While these bills aimed to curb online piracy, many fear that they also pave the way for widespread internet censorship. Although consideration of SOPA and PIPA has now been “postponed,” the bills and the protests raise the issue of who has the authority to control access to knowledge. The different visual and technological ways that websites protested SOPA and PIPA demonstrate the importance we as a culture place on unfettered access to information. In imagining what a censored internet might be like, the protests also show how much the medium — in this case, technology — shapes our individual and collective knowledge and what kind of a threat censorship would be. In additional to concerns about free speech and access to information, the protests also remind us how many profitable businesses are based on assumptions that those things will remain uncensored.

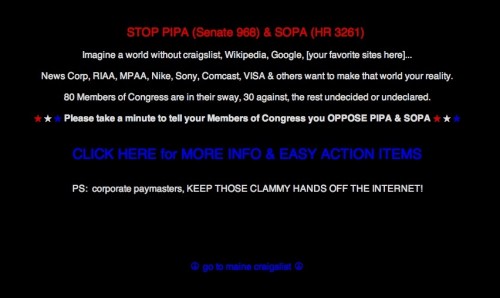

Many sites (such as Craigslist, Pinterest, and icanhascheezburger, screencaps below) took a traditional web protest approach by posting informational messages encouraging visitors to take action against the bills:

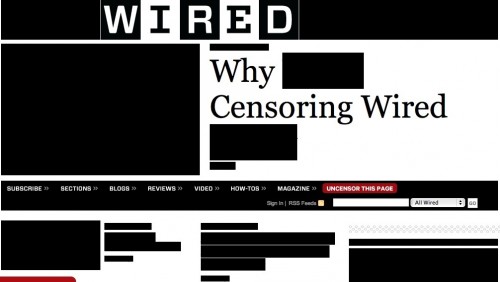

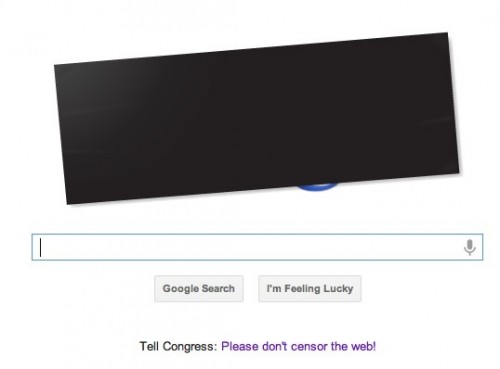

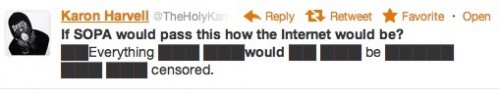

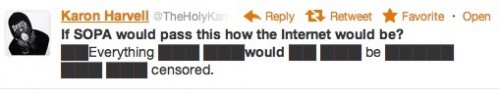

Other websites (WordPress, Wired, Google), along with Facebook status updates and Tweets, visually depicted what internet censorship would look like. This kind of protest is particularly visually powerful — stark black blocks out the text, making the message unreadable:

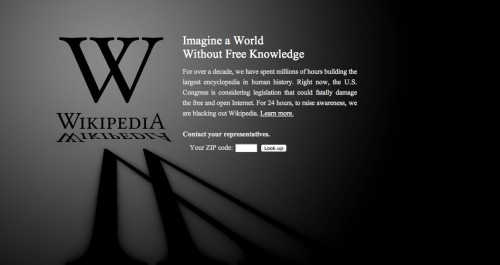

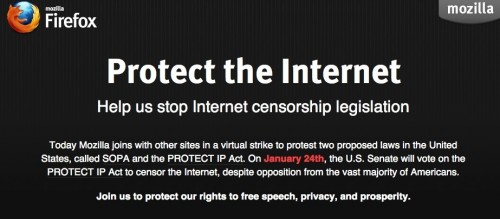

Others shut down altogether (like Wikipedia, Reddit, MoveOn, and Mozilla), essentially removing their website’s resources and information for 24 hours:

Others shut down altogether (like Wikipedia, Reddit, MoveOn, and Mozilla), essentially removing their website’s resources and information for 24 hours:

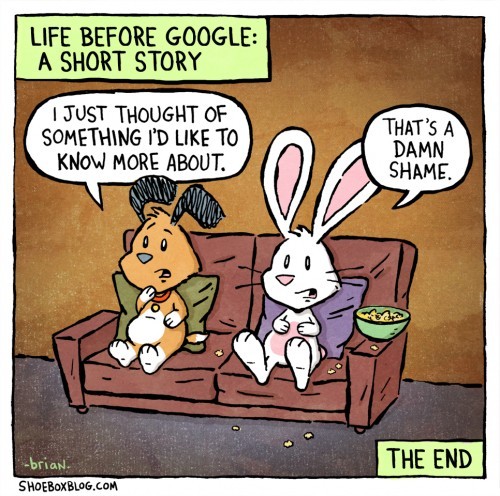

Many of us are fortunate to take for granted open, easy access to information, including open access to everything on the internet (though the continued existence of a digital divide makes such information more available to some than others, and school districts routinely censor online content for students). The protests of SOPA and PIPA illustrate how much we rely on technology for access to information by raising important questions about what censorship would mean for access to knowledge. Seemingly boundless information is at the tips of our fingers everywhere we go:

(Via Shoebox Blog.)

As the cartoon shows, our knowledge is shaped by what medium is physically available to us for seeking new information. Students in my classes can’t fathom a time when they couldn’t look up any bit of information they needed on Google. They can’t imagine the way I used to do research for a school paper– by consulting my family’s dusty encyclopedia set, or heading down to the library. Though their experience is physically removed from the research librarian’s desk, they have access to much more information than I ever did in my local library. The protests against SOPA and PIPA — the website outages and blacked out texts — make real the idea that if the internet were censored, our avenues for learning would shrink.

On January 18th, 2012 many sites on the internet went “black” to protest the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA), including Wikipedia, Boing Boing, Reddit, Cheezburger, Craig’s List, WordPress, Wired, and Sociological Images too, to name a few (in solidarity, Google blacked out it’s logo). While written ostensibly to make it easier to stop pirating of music, movies, and other media, opponents argue that the Acts are so penalizing and over-reaching that they would essentially criminalize sharing and creativity. There’s a great slideshow of the blacked out sites at the Los Angeles Times.

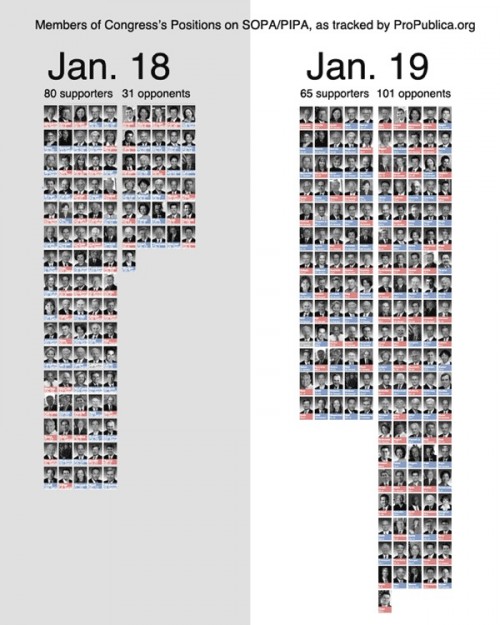

The next day proved that this online action made a large difference, at least in the short run. Seventy Congress members switched their positions or newly decided to stand against the Acts (Boing Boing). Congress has postponed actions on the Act, which was slotted for today.

From the point of view of Sociological Images, this is a much needed victory. From a sociological point of view, it is another illustration of how the internet creates both new legal issues and facilitates new social movement tactics.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

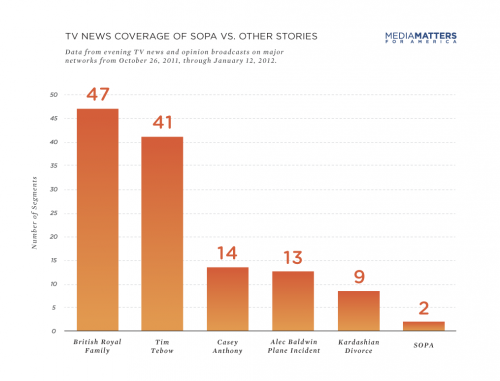

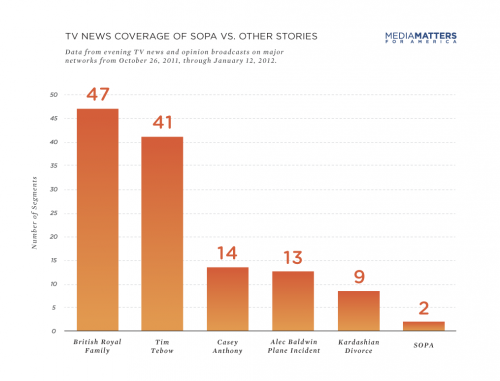

Sociologists and others use the term “agenda setting” to describe the way that the media focuses our attention on some things and not others. In this way, media actors may not control how we think about things, but they may very well control what we think about.

This instance of agenda setting involves SOPA, the Stop Online Piracy Act. Media Matters put together this figure illustrating the relative number of television segments given to SOPA and other issues — the British Royal Family, the football player Tim Tebow, Casey Anthony and her missing daughter, Alec Baldwin’s behavior on a plane, and the Kardashian divorce — between October 26th, 2011 and January 12th of this year.

Data like this is often used to explain why Americans tend to be quite uninformed about important issues. For more examples, see this post comparing the covers of TIME and Newsweek in the U.S. and elsewhere. See also: Setting the Agenda on Trump and Setting the Agenda on Janet Jackson’s “Wardrobe Failure.”

Data like this is often used to explain why Americans tend to be quite uninformed about important issues. For more examples, see this post comparing the covers of TIME and Newsweek in the U.S. and elsewhere. See also: Setting the Agenda on Trump and Setting the Agenda on Janet Jackson’s “Wardrobe Failure.”

Thanks to Dolores R. for the tip! Via Socialist Texan.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

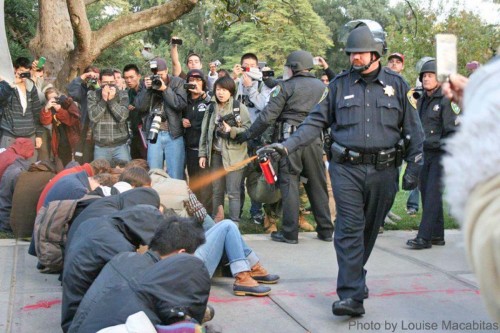

Last Friday at the University of California-Davis, a group of student Occupy Wall Street protesters were pepper sprayed by university police for refusing to vacate the campus quad. As Lisa pointed out, thanks to the widespread availability of phones with cameras, the incident was photographed and recorded by dozens of onlookers. As a result, images and videos of the pepper spraying incident have flooded the internet. One video has received over 1.7 million views on Youtube; another shorter clip has almost 1 million.

One image, taken by Louise Macabitas, has become iconic (via San Francisco Citizen):

The image is striking in several ways. First, nearly everyone watching has a camera or cell phone and is documenting the event. Second, there is a strong visual separation of the police and protesters — the police are standing, while the protesters are seated. Third, the police officer who is spraying protesters has a very casual, removed demeanor and stance. There is no direct confrontation occurring to seemingly warrant such an action. The image depicts an imbalance of power, as students crouch and hide their faces from the pepper spray wielded by campus police.

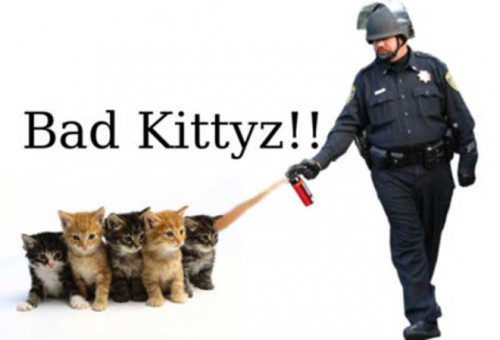

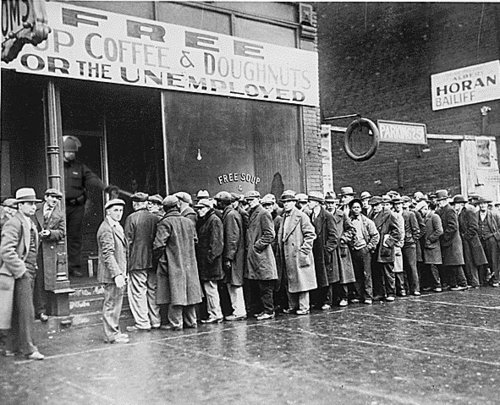

The image has so much visual power that it has taken off as an online meme. Consider these variations, all posted at Wired.

I think this meme is itself a form of visual protest. The variations on the original image reinforce the perception that the police officer’s actions were inappropriate and an abuse of power. The use of famous scenes and works of art creates a cartoonish depiction of inequality and injustice, of someone using their power unjustly against those who obviously have less power — children, kittens, the unemployed, etc. (via the Pepper Spraying Cop tumblr):

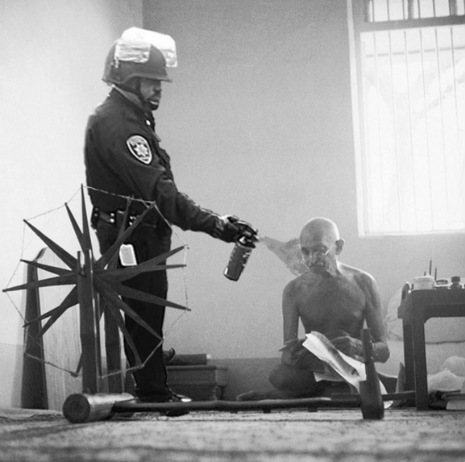

Other images present the officer’s actions are an affront to justice, by using images associated with freedom, democracy, or peaceful resistance (found at the Pepper Spraying Cop tumblr and CyBeRGaTa:

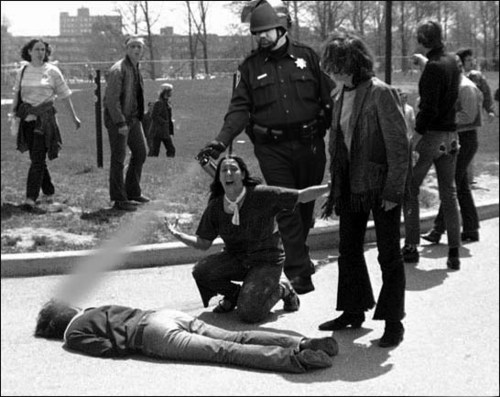

This one merges the image with another iconic photo of an abuse of police power on campus, the shooting at Kent State University in 1970 (via CyBeRGaTa):

Reproducing this image of injustice online is a form of visual protest, spreading images of perceived injustice in different visual contexts across the internet. The meme is a commentary on how we culturally and historically understand power inequalities and the limits of appropriate uses of power.

Yet, while this is a powerful form of protest that draws important connections, the meme also removes the officer, Lt. John Pike, from the original context of his actions. This runs the danger of focusing on Pike as a lone actor, and not an individual whose actions are shaped within the larger institutional system of justice. As Alexis Madrigal warns us in “Why I Feel Bad for the Pepper-Spraying Policeman, Lt. John Pike“:

Structures, in the sociological sense, constrain human agency. And for that reason, I see John Pike as a casualty of the system, too. Our police forces have enshrined a paradigm of protest policing that turns local cops into paramilitary forces. Let’s not pretend that Pike is an independent bad actor. Too many incidents around the country attest to the widespread deployment of these tactics. If we vilify Pike, we let the institutions off way too easy.

Hennessy Youngman is one of things-on-the-internetz that validates the entire enterprise. In the fast and fascinating 10 minute clip here, Youngman traces the history of performance art, linking it to Occupy and our contemporary engagement with the internet. Oh, and totally worth watching to the end.

Hennessy Youngman is one of things-on-the-internetz that validates the entire enterprise. In the fast and fascinating 10 minute clip here, Youngman traces the history of performance art, linking it to Occupy and our contemporary engagement with the internet. Oh, and totally worth watching to the end.

(Hennessy, if you’re reading, I was the one that tweeted at you to do a video about The Levitated Mass. Nobody could do it quite like you! PS – whisky is my drink too.)

Also from Hennessy Youngman:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Dominant groups have the power to control representations of less-powerful groups. They exert an out-of-proportion influence on their cultural portrayals.

Dominant groups have the power to control representations of less-powerful groups. They exert an out-of-proportion influence on their cultural portrayals.

We’ve previously featured objections to simplistic portrayals of the enormous continent of Africa, especially as a place that is primitive and hopelessly burdened by death, disease, poverty, corruption, and other problems. Chimamanda Adichie, for example, objects to the “single story of Africa” and Binyavanga Wainaina tell us how not to write about Africa. Elsewhere, we’ve illustrated how the bustling city of Nairobi is portrayed as a savanna with giraffes and elephants.

An organization called Mama Hope, sent in by Jennifer C., seeks to challenge this perception. They want the world to think of Africa as a place of hope and possibility. To this end, Mama Hope is producing videos that “…feature the shared traits that make us all human— the dancing, the singing, the laughter…” They look like this:

The effort reminds me of the “Smiling Indians” and “More Than That” videos, sent in by Katrin and Anna W. The first addressed the stereotype of the “stoic Indian,” while the second is designed to counterbalance the common portrayal of reservations as miserable places full of one-dimensional hopeless people (something we are certainly sometimes guilty of).

Smiling Indians:

More Than That…:

These videos are examples of the way that the democratizing power of new technologies (both the internet in general and the relatively easy ability to take video and edit) are offering marginalized peoples an opportunity to contest representations by dominant groups.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Cross-posted at Compassionate Societies.

A new study from Pew, based upon a large national survey, found that people reported a lot more cruelty and the absence of kindness that many would expect. This implies that social networking sites (SNS) could use a lot more compassion.

Among adults, 85% say that their experience on the sites is that people are mostly kind. Fewer teens said the same, only 69%. More, social networking sites contributed to real life problems: including arguments and physical fights with friends, family members, teachers, or co-workers. In all categories, teens were about twice as likely to report that SNS got them into trouble:

Racial minority populations encountered an even more cruel environment on SNS. Forty-two percent of Black and 33% of Hispanic SNS users said they frequently or sometimes saw language, images, or humor that they found offensive, compared with 22% of White SNS users.

Interestingly, people who used social networking sites on a daily basis were far more likely to report experiencing negative things:

SNS users also reported positive experiences, suggesting that, for many, social networking is a mixed bag of good and bad:

————————

Ron Anderson, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota, has written many books and hundreds of articles, mostly on technology. In his retirement, he is doing research and writing on compassion and suffering and maintains the website CompassionateSocieties.org.

Last Wednesday, January 20 18, over 7000 websites participated in a massive protest opposing bills H.R. 3261, the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and S. 968, the PROTECT IP Act (PIPA). While these bills aimed to curb online piracy, many fear that they also pave the way for widespread internet censorship. Although consideration of SOPA and PIPA has now been “postponed,” the bills and the protests raise the issue of who has the authority to control access to knowledge. The different visual and technological ways that websites protested SOPA and PIPA demonstrate the importance we as a culture place on unfettered access to information. In imagining what a censored internet might be like, the protests also show how much the medium — in this case, technology — shapes our individual and collective knowledge and what kind of a threat censorship would be. In additional to concerns about free speech and access to information, the protests also remind us how many profitable businesses are based on assumptions that those things will remain uncensored.

Many sites (such as Craigslist, Pinterest, and icanhascheezburger, screencaps below) took a traditional web protest approach by posting informational messages encouraging visitors to take action against the bills:

Other websites (WordPress, Wired, Google), along with Facebook status updates and Tweets, visually depicted what internet censorship would look like. This kind of protest is particularly visually powerful — stark black blocks out the text, making the message unreadable:

Others shut down altogether (like Wikipedia, Reddit, MoveOn, and Mozilla), essentially removing their website’s resources and information for 24 hours:

Others shut down altogether (like Wikipedia, Reddit, MoveOn, and Mozilla), essentially removing their website’s resources and information for 24 hours:

Many of us are fortunate to take for granted open, easy access to information, including open access to everything on the internet (though the continued existence of a digital divide makes such information more available to some than others, and school districts routinely censor online content for students). The protests of SOPA and PIPA illustrate how much we rely on technology for access to information by raising important questions about what censorship would mean for access to knowledge. Seemingly boundless information is at the tips of our fingers everywhere we go:

(Via Shoebox Blog.)

As the cartoon shows, our knowledge is shaped by what medium is physically available to us for seeking new information. Students in my classes can’t fathom a time when they couldn’t look up any bit of information they needed on Google. They can’t imagine the way I used to do research for a school paper– by consulting my family’s dusty encyclopedia set, or heading down to the library. Though their experience is physically removed from the research librarian’s desk, they have access to much more information than I ever did in my local library. The protests against SOPA and PIPA — the website outages and blacked out texts — make real the idea that if the internet were censored, our avenues for learning would shrink.

On January 18th, 2012 many sites on the internet went “black” to protest the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA), including Wikipedia, Boing Boing, Reddit, Cheezburger, Craig’s List, WordPress, Wired, and Sociological Images too, to name a few (in solidarity, Google blacked out it’s logo). While written ostensibly to make it easier to stop pirating of music, movies, and other media, opponents argue that the Acts are so penalizing and over-reaching that they would essentially criminalize sharing and creativity. There’s a great slideshow of the blacked out sites at the Los Angeles Times.

The next day proved that this online action made a large difference, at least in the short run. Seventy Congress members switched their positions or newly decided to stand against the Acts (Boing Boing). Congress has postponed actions on the Act, which was slotted for today.

From the point of view of Sociological Images, this is a much needed victory. From a sociological point of view, it is another illustration of how the internet creates both new legal issues and facilitates new social movement tactics.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Sociologists and others use the term “agenda setting” to describe the way that the media focuses our attention on some things and not others. In this way, media actors may not control how we think about things, but they may very well control what we think about.

This instance of agenda setting involves SOPA, the Stop Online Piracy Act. Media Matters put together this figure illustrating the relative number of television segments given to SOPA and other issues — the British Royal Family, the football player Tim Tebow, Casey Anthony and her missing daughter, Alec Baldwin’s behavior on a plane, and the Kardashian divorce — between October 26th, 2011 and January 12th of this year.

Data like this is often used to explain why Americans tend to be quite uninformed about important issues. For more examples, see this post comparing the covers of TIME and Newsweek in the U.S. and elsewhere. See also: Setting the Agenda on Trump and Setting the Agenda on Janet Jackson’s “Wardrobe Failure.”

Data like this is often used to explain why Americans tend to be quite uninformed about important issues. For more examples, see this post comparing the covers of TIME and Newsweek in the U.S. and elsewhere. See also: Setting the Agenda on Trump and Setting the Agenda on Janet Jackson’s “Wardrobe Failure.”

Thanks to Dolores R. for the tip! Via Socialist Texan.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Last Friday at the University of California-Davis, a group of student Occupy Wall Street protesters were pepper sprayed by university police for refusing to vacate the campus quad. As Lisa pointed out, thanks to the widespread availability of phones with cameras, the incident was photographed and recorded by dozens of onlookers. As a result, images and videos of the pepper spraying incident have flooded the internet. One video has received over 1.7 million views on Youtube; another shorter clip has almost 1 million.

One image, taken by Louise Macabitas, has become iconic (via San Francisco Citizen):

The image is striking in several ways. First, nearly everyone watching has a camera or cell phone and is documenting the event. Second, there is a strong visual separation of the police and protesters — the police are standing, while the protesters are seated. Third, the police officer who is spraying protesters has a very casual, removed demeanor and stance. There is no direct confrontation occurring to seemingly warrant such an action. The image depicts an imbalance of power, as students crouch and hide their faces from the pepper spray wielded by campus police.

The image has so much visual power that it has taken off as an online meme. Consider these variations, all posted at Wired.

I think this meme is itself a form of visual protest. The variations on the original image reinforce the perception that the police officer’s actions were inappropriate and an abuse of power. The use of famous scenes and works of art creates a cartoonish depiction of inequality and injustice, of someone using their power unjustly against those who obviously have less power — children, kittens, the unemployed, etc. (via the Pepper Spraying Cop tumblr):

Other images present the officer’s actions are an affront to justice, by using images associated with freedom, democracy, or peaceful resistance (found at the Pepper Spraying Cop tumblr and CyBeRGaTa:

This one merges the image with another iconic photo of an abuse of police power on campus, the shooting at Kent State University in 1970 (via CyBeRGaTa):

Reproducing this image of injustice online is a form of visual protest, spreading images of perceived injustice in different visual contexts across the internet. The meme is a commentary on how we culturally and historically understand power inequalities and the limits of appropriate uses of power.

Yet, while this is a powerful form of protest that draws important connections, the meme also removes the officer, Lt. John Pike, from the original context of his actions. This runs the danger of focusing on Pike as a lone actor, and not an individual whose actions are shaped within the larger institutional system of justice. As Alexis Madrigal warns us in “Why I Feel Bad for the Pepper-Spraying Policeman, Lt. John Pike“:

Structures, in the sociological sense, constrain human agency. And for that reason, I see John Pike as a casualty of the system, too. Our police forces have enshrined a paradigm of protest policing that turns local cops into paramilitary forces. Let’s not pretend that Pike is an independent bad actor. Too many incidents around the country attest to the widespread deployment of these tactics. If we vilify Pike, we let the institutions off way too easy.