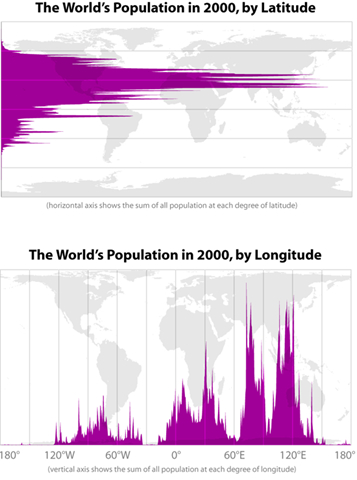

Martin W. found two neat graphs over at The Horizon that show the 2000 world population’s distribution by latitude and longitude.

It’s not that they’re shocking, in the sense that of course we’d expect more people to be living in temperate/tropical latitudes than in the Arctic, given availability of resources to support human settlements (at least until the development of modern conveniences like heat, canned food, and quick transportation to get them to people far from their sources). And the huge spikes where China and India are make sense too. But I still think it’s visually striking to see, for instance, how little of the world’s population is located in the Americas. And the patterns we see here certainly have important implications for global economic development and the likely highly uneven distribution of negative impacts of environmental/climate change, among other issues.

But then, I’m also just a geek about maps and like looking at them in general.