One thing I do in my classes is show my students evidence that things that seem very individualistic and unique are often influenced by social patterns to a much higher degree than they’d think. I often bring up the example of baby names. On one level, it’s an extremely personal and individual-(family)-level decision: people pick names they like and that are meaningful to them, and many would deny that larger social influences had anything to do with what they named their child. And yet names come into and out of fashion quite abruptly among lots of people at the same time, indicating that either a whole lot of people somehow independently make the same decision or that there’s a social aspect to baby naming–so naming your baby “Isabel” might not be the totally unique, personal decision you thought.

Well, now I can quantify this. It turns out the Social Security Administration has this nifty little website where you can put in any year since 1880 and find out the most popular names (from the top 20 up to the top 1000) boys’ and girls’ names for that year, including percentages of babies born that year given each name.

Here are the top 10 names for boys and girls in 1916 and 2016.

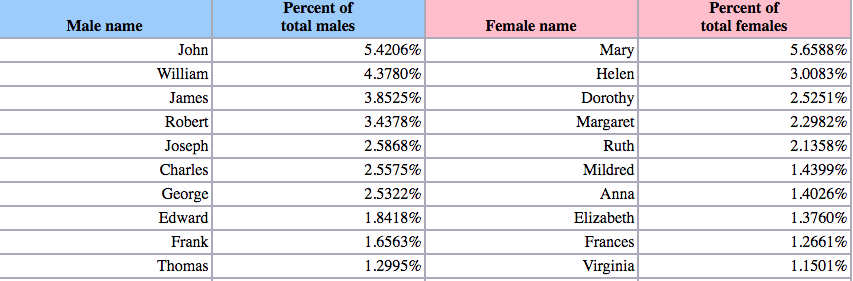

From 1916:

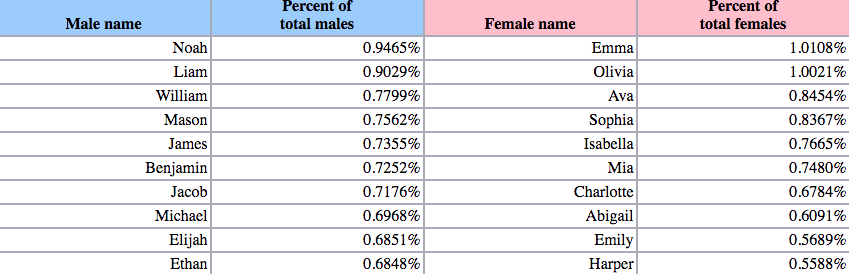

From 2016:

Only 1 name (William) that was most popular in 1916 was still in the top 10 in 2016. There was also a lot more concentration in 1916 than in 2016. For boys, the top name in 1916 made up 5.4% of names, while in 2016 the most popular name was only 0.9% of all names. For girls it went from 5.7% to 1.0% (I rounded all percentages to the nearest tenth of a percent). Also, in the past there was more clumping in boys’ names than girls’ names, though this is no longer the case. So in addition to just pointing out that preference for names has changed over time, it might be interesting to discuss the increasing emphasis in our culture on trying to have a “unique” name for kids that express their personality, so that there is more diversity in kids’ names today than in the past, and why until recently this was more true for girls than boys.

Jay L. provided a link to this neato site where you can type in any name and get an immediate graphic of its frequency per million babies. Totally addicting!

NEW: Abby sent in a link to Freakonomics Watch with the following explanation:

The other day a friend of mine said he was reading Freakonomics and there is a chapter on baby naming…the chapter presents a theory for how baby names become popular. People of higher education and socioeconomic status tend to seek out unusual names for their babies, which are then increasingly adopted by the masses. Once the names become popular, cultural elites seek out a new batch of unusual names, and so on. Based on this theory, the book gives a list of names that they predict will be popular by 2015.

You can find a table tracking the popularity of the Freakonomics predictions here. Abby was embarrassed to see that her 3-month-old son’s name is on the list.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.