In honor of Prune Breakfast Month, we’re re-running this post on the prune.

What’s a prune?

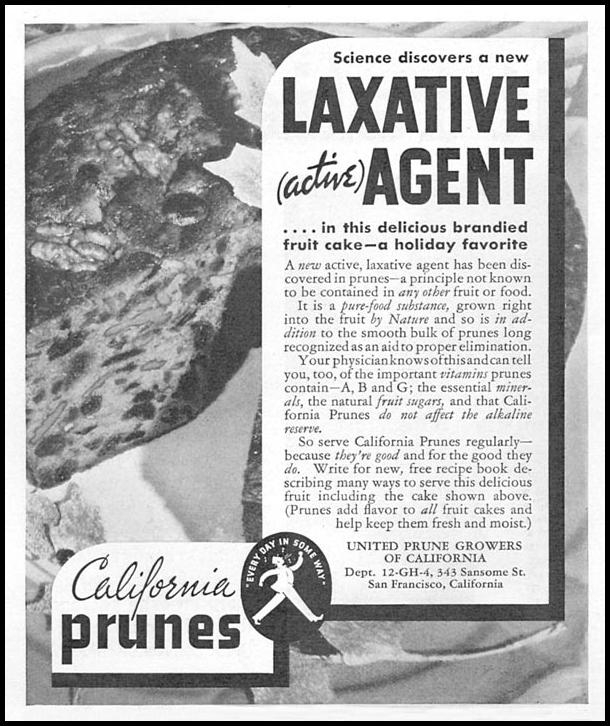

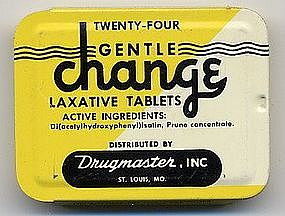

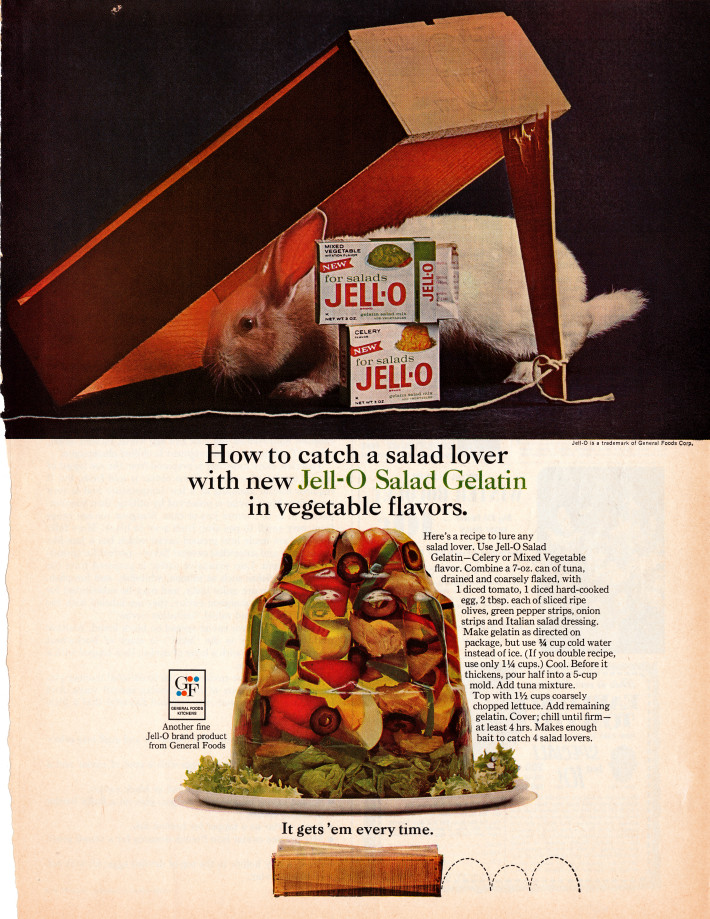

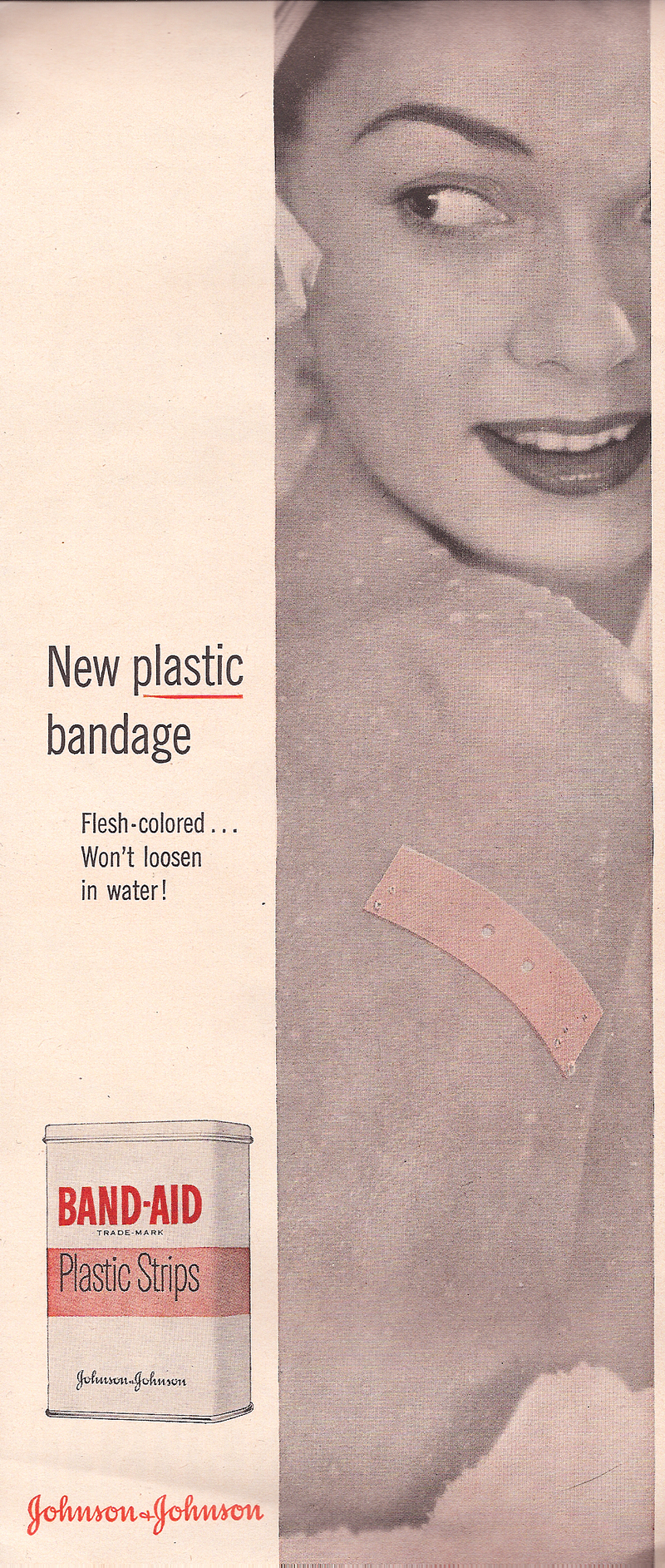

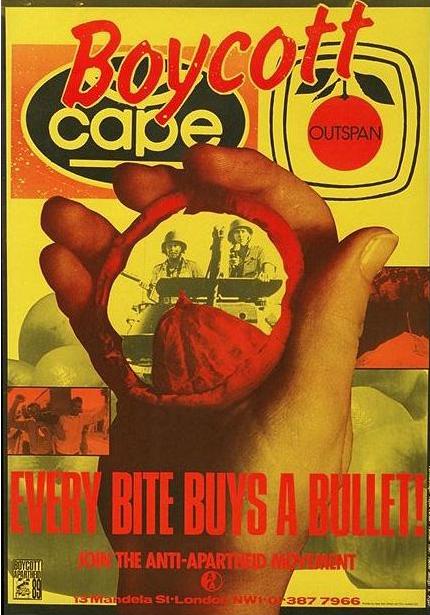

Answer One, the social construction: Prunes are dried fruit you serve to old people who need help with their bowel movements (though, hilariously, it wasn’t always that way). This is epitomized by the Sunsweet slogan, “The Natural Way to Go” and illustrated in the following eclectic combination of cultural items:

Not exactly an appetizing advertising campaign, eh? (Though my grandpa, and all three uncles, would totally wear that hat.)

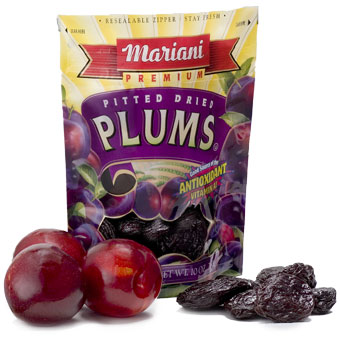

Answer Two, the purely descriptive answer: Prunes are dried plums. Which, of course, they are. Lovely, gorgeous, beautiful plums:

Mariani, not stupid, recently changed the name of their product from “prunes” to “dried plums,” instantly transforming their product from one for the constipated elderly to one for connoisseurs of exotic dried fruits.

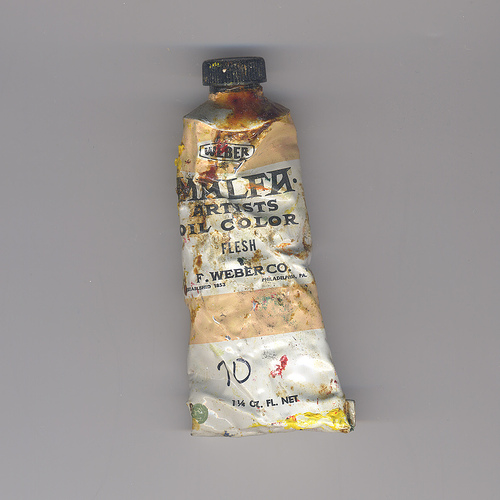

From prunes:

Words matter, is all.

(Images borrowed from here, here, here, here, here, and here.)

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.