PBS has a gallery of images of oral contraceptives that provides a nice illustration of the way product design can be used as a form of behavior modification, while also needing to adapt to the way people actual use products — or forget to do so, the ever-present problem with the pill.

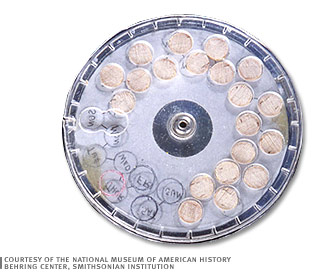

Initially , the pill came in bottles, like other prescriptions:

Notice the bottle contains 100 pills; there was no effort to package it into quantities for a single month. Women were supposed to take 20 pills in a row, then none during their period. It was up to them to keep track of everything and remember when it was time to start taking the pills again.

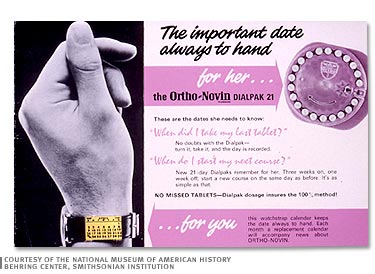

In 1962, an engineer created a prototype of a dispenser pack, designed to hold exactly a month’s worth of pills and help women remember to take them correctly:

The first contraceptive in a pack of this type, Dialpak, appeared the next year; oral contraceptives packaging has been designed to help women remember to take them accurately ever since. This became a major selling point, with Dialpak 21 even offering a small calendar you could attach to a special watch band so you could more easily keep track of whether you’d taken the pill:

In 1965, Eli Lilly introduced a new packaging design, with differently-colored pills arranged in a sequence; however, it didn’t label the days of the week, so it didn’t help women figure out if they’d remembered to take their pill on any given day:

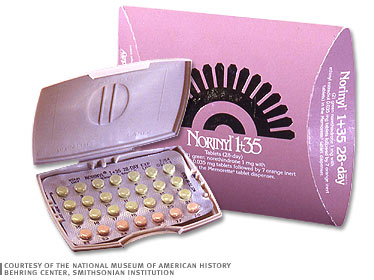

Norinyl came in a package that took the sequential design but added several features that enhanced compliance. An extra pill was added, so that pills with active ingredients were taken for 21 days, not 20. Then a row of placebo pills were added so that women took a pill every day of the month, so they were less likely to forget to start a new pack:

When we think about the emergence and success of the pill, we tend to focus on the product itself. But the packaging tells an interesting story on its own. The pharmacological effectiveness of oral contraceptives meant little if women forgot to take them reliably. The design of the packaging helped play a crucial role, increasing users’ ability to follow the prescribed schedule.

Today, there’s an entire trade organization, the Healthcare Compliance Packaging Council, dedicated to promoting attention to the design of packaging as an important element in all areas of healthcare. The pill was the first prescription drug sold in a so-called “compliance pack,” serving as an example of the potential effectiveness of packaging design as a way to encourage patients’ conformity to prescribed medication regimens.