In 1919 the U.S. federal government passed the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” Alcohol was banned. Well, kind of. Two groups were still allowed to buy and disseminate alcohol: clergy and physicians (source).

Clergy were still allowed to purchase wine for sacrament (reportedly leading to many a falsely-devotional newly-certified minister, priest, or rabbi illegally selling bucket loads of liquor to the rest of us). And physicians were allowed to prescribe liquor for medicinal purposes. Alcohol, it was believed, was energizing and it was used to treat anemia, tuberculosis, typhoid, pneumonia, and high blood pressure. Pharmacies did a booming business in those years, as you might imagine.

According to the Rose Melnick Medical Museum:

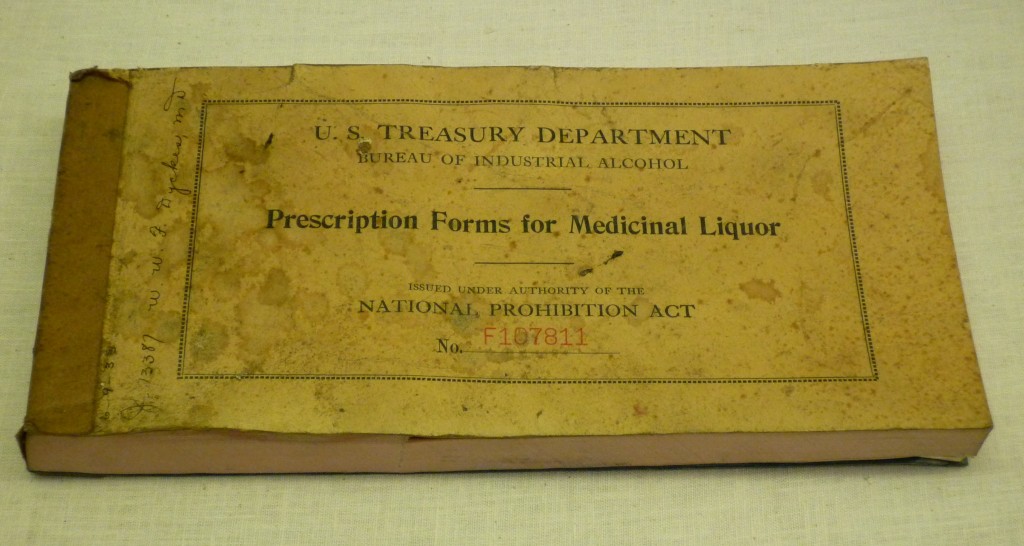

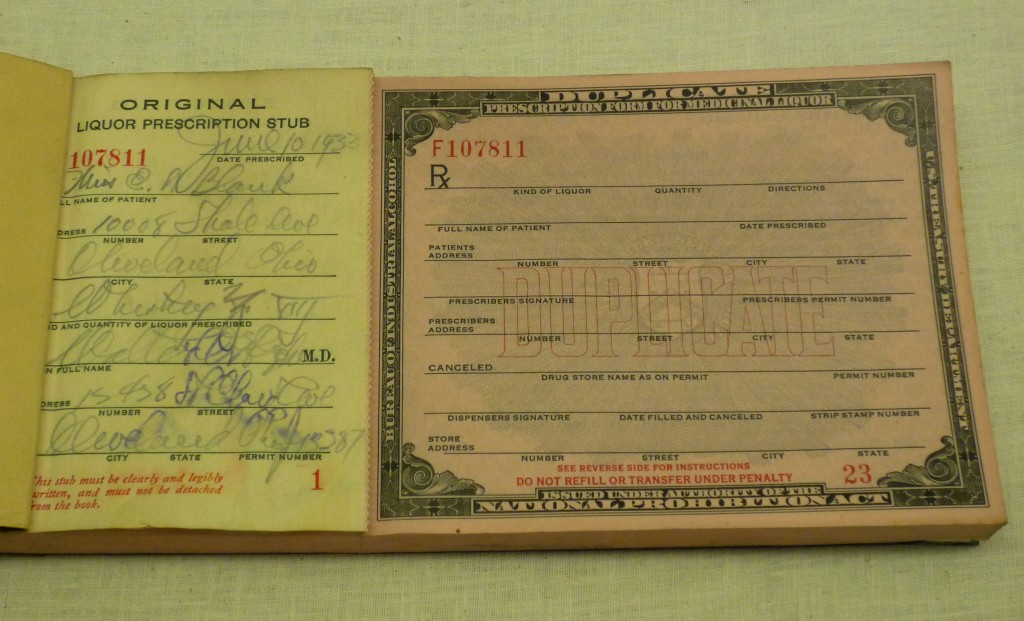

This new law required physicians to obtain a special permit from the prohibition commissioner in order to write prescriptions for liquor.The patient could then legally buy liquor from the pharmacy or the physician. However, the law also regulated how much liquor could be prescribed to each patient.

…

Patients of all ages used alcohol. A common adult dose was about 1 ounce every 2-3 hours. Child doses ranged from 1/2 to 2 teaspoons every three hours.

Physicians prescribed their “medicine” with prescription pads doled out by the commissioner:

Unfortunately for some, you couldn’t prescribe beer.

Even after Prohibition was lifted in 1933, pharmacies sold plenty of liquor. In many places women were banned from bars and saloons, so while men visited the bartender, women visited the doctor. Visit our post on The Stormin’ of the Sazerac to see a great vintage picture of a group of women enjoying the famous cocktail on the first day they were allowed to drink at The Roosevelt Bar, New Orleans.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.