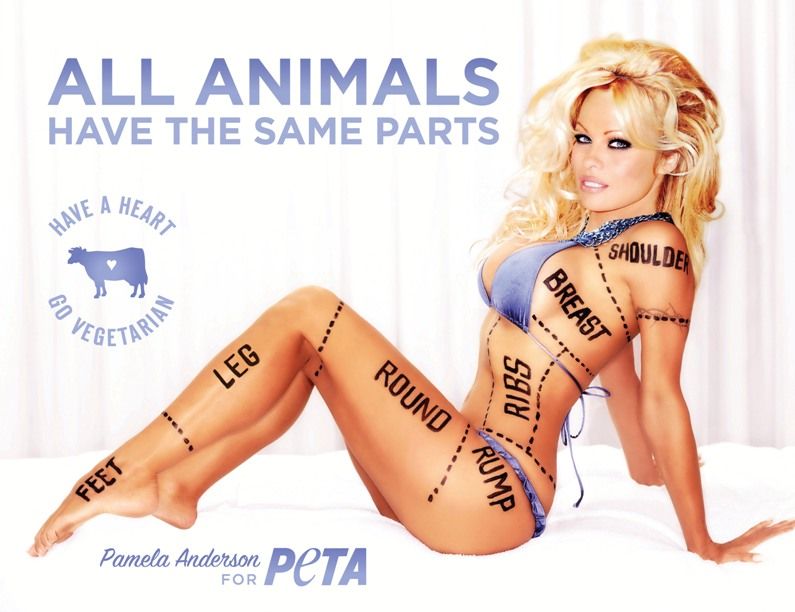

Valerie A. sent along a short video by Chris Muther, at the Boston Globe. He offers a humorous history of changing bodily ideals for both men and women. He explains the shifts as rebellion against our parents and what they found sexy. I find this explanation uncompelling, though. You?

See also our recent post on bodily diversity among Olympic athletes and our fashion fantasy in which everyone emphasized whatever (weird) bodies they were born with.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.