Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

You’re not going to persuade a conservative by appealing to liberal moral principles. Tell a Tea Party type that industrial waste harms the environment and should be regulated, you won’t get very far. But if you appeal to conservative moral principles, the story goes, you might have more luck.

I’ve been skeptical about Jonathan Haidt’s conservative moral principles — group loyalty, purity, and authority — mostly because they are used to justify practices I find wrong or immoral. Things like anti-gay legislation, torture, assassination, terrorism, etc.

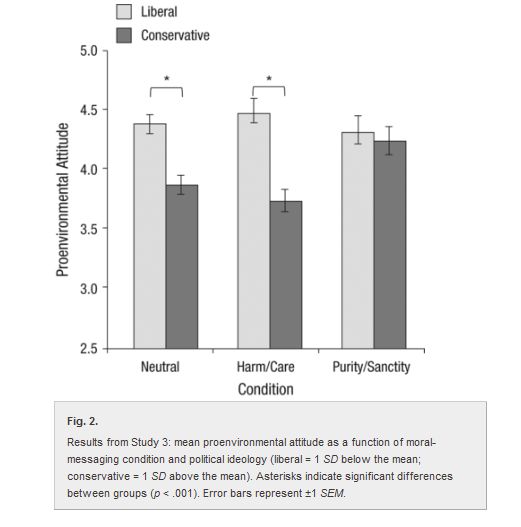

But a recent experimental study by UC Berkeley’s Robb Willer shows that the right kind of persuasion can make conservatives a bit more leftist on the environment. In his study, participants read a pro-environmental message that was based either on “Harm/Care” (liberal logic) or on “Purity/Sanctity”(conservative logic) along with photos that matched the appeal.

- Harm/Care: A destroyed forest of tree stumps, a barren coral reef, and cracked land suffering from drought.

- Purity/Sanctity: A cloud of pollution looming over a city, a person drinking contaminated water, and a forest covered in garbage.

There was also a Neutral condition: “an apolitical message on the history of neckties.” (Willer has a fine sense of humor.)

Participants were then asked questions to determine their support for pro-environmental legislation.

For people who identified themselves as liberal, the type of material they saw — Harm, Purity, or Necktie — made no difference in their environmental position. Conservatives, as expected, were generally cooler to environmental legislation, but only in the Neutral and Harm conditions. Once they were shown the Purity materials, conservatives were as pro-environment as the liberals.

Other aspects of the conservative mind-set seem to go along with this emphasis on purity: simplicity rather than complexity and a lower tolerance of ambiguity. It’s a view that sees the need for clearly marked and rigidly enforced boundaries — the boundaries of the nation, the boundaries of the individual, the boundaries of cognitive categories.

Ultimately, the findings suggest that common ground between liberals and conservatives may not be as impossible to find as it may seem.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.