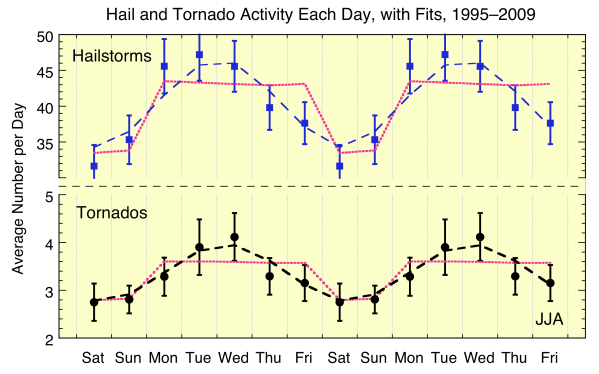

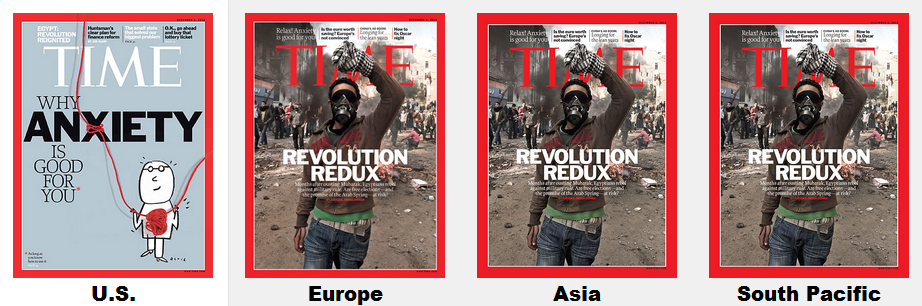

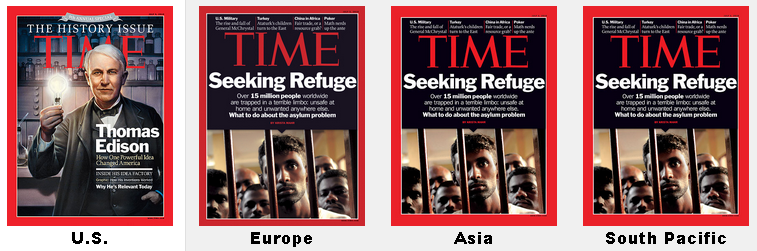

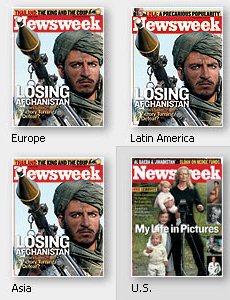

I’m a particular fan of looking at ways that society and nature intersect and a new study is a fantastic example. Analysis of 15 years of storm data revealed that twisters and hailstorms were significantly more likely to occur during the week as compared to weekends.

According to the authors, Daniel Rosenfeld and Thomas Bell, the cause is pollution caused by commuting. Charles Choi, writing for National Geographic, explains:

…moisture gathers around specks of pollutants, which leads to more cloud droplets. Computer models suggest these droplets get lofted up to higher, colder air, leading to more plentiful and larger hail.

Understanding how pollution can generate more tornadoes is a bit trickier. First, the large icy particles of hail that pollutants help seed possess less surface area than an equal mass of smaller “hydrometeors”—that is, particles of condensed water or ice.

As such, these large hydrometeors evaporate more slowly, and thus are not as likely to suck heat from the air. This makes it easier for warm air to help form a “supercell,” the cloud type that usually produces tornadoes and large hail.

So, there you have it. No need to choose between nature and nurture. We interact with our environment and shape it, just as it shapes us.

(Via BoingBoing.)

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.