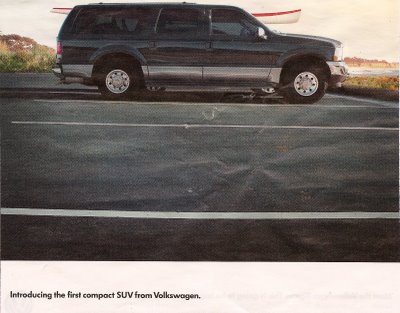

Exactly in line with Gwen’s last post on symbolizing an eco-friendly identity, Dorothee H. sent us a link to a commerical linking leftist politics to the smart car. I think Gwen’s comments say it all and Dorothee’s submission illustrates it beautifully:

See also this commercial that uses pro-communist sentiment to market a car.