O.S. sent in this neat video found at Flowing Data that illustrates the spread of Wal-Mart and Sam’s Club stores across the U.S. since the early 1960s:

consumption

Dmitriy T.M. sent in this video about the production and marketing of bottled water. It’s a little over-the-top at the beginning, but it brings up a lot of really interesting issues surrounding the selling of a product that is, in the U.S., available to the vast majority of people at a much cheaper price in their kitchen. And yes, I know, some people’s water tastes terrible, etc. etc. The point, in general, still stands that we are spending a lot of money and resources carting water around, and I find the advertising for bottled water fascinating.

Also see The Story of Stuff.

Since I’ve been obsessed in recent months with marketing techniques and the social psychology of shopping, Dmitriy T.M. sent me a video found at Time; in the video Martin Lindstrom argues that sound can be used to encourage shoppers to buy more items.

So if you need to increase sales in your store, get a bunch of babies and have them sitting around giggling. You don’t even have to pay sound licensing fees!

NOTE: I see that a lot of commenters are discussing their personal lack of reaction to the sound of giggling babies, etc. I totally get it–I raised an eyebrow as well. But we should keep in mind that there may be a difference between actively reacting to something or caring about it greatly (say, loving kids) and being indirectly influenced by sounds that might vaguely evoke some element of it. Of course, from the video we don’t know if any business has actually been successful at getting people to buy things by using sounds similar to babies giggling (or water being poured), only that people seem to react positively to those sounds in the lab. So I don’t know how much legitimacy there is to this, but I know marketers have definitely tried to use smells to influence people to linger in an area, hopefully then leading to higher sales.

Other posts on marketing and psychology: restaurant menus and the meaningless discount.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

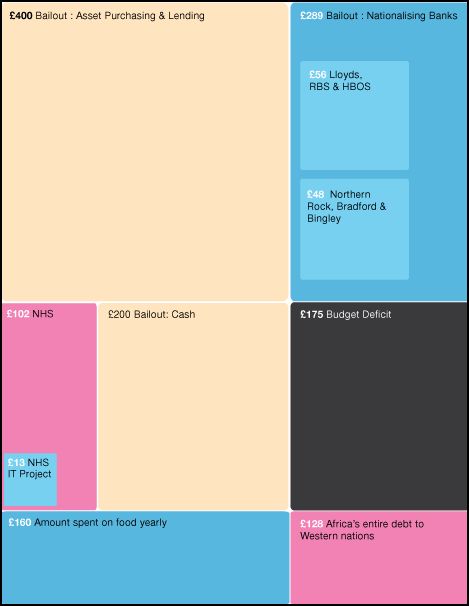

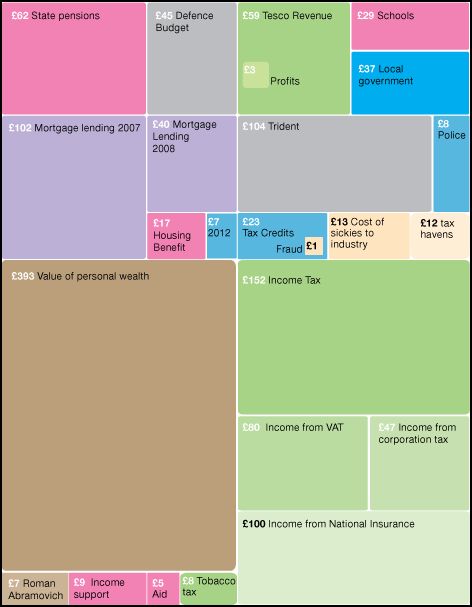

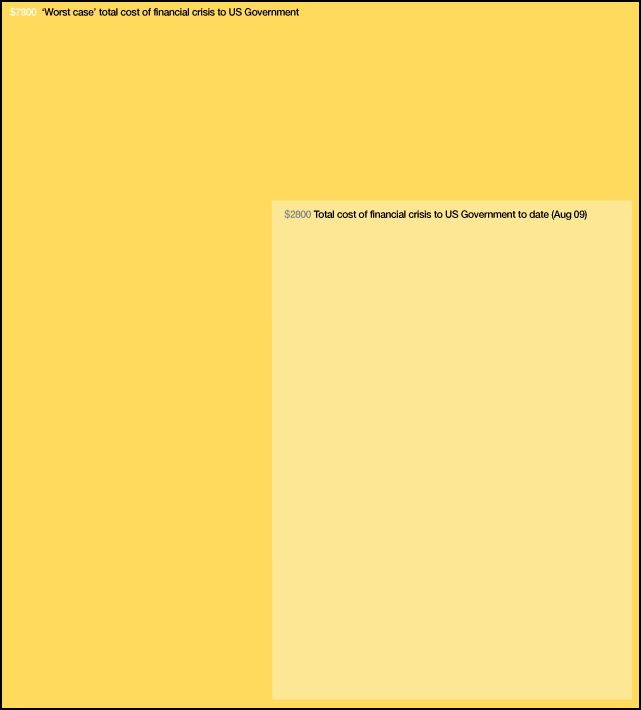

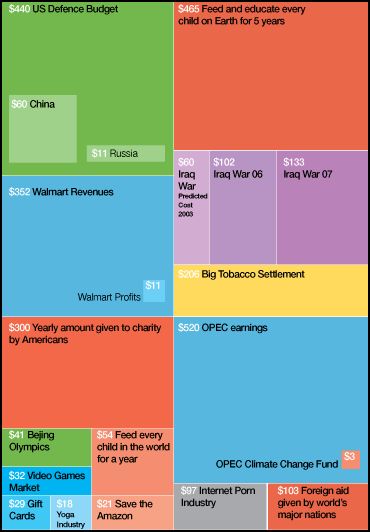

Katrin sent along links to visual portrayals of how much money goes, or could go, to various causes. While sometimes it’s hard to comprehend what a billion, or 300 billion, dollars amounts to, these images give us perspective on just where our priorities lie. The segments below are clipped from the visuals for the U.K. and the U.S. at Information is Beautiful.

The British example nicely illustrates how little social services like education, police, and welfare cost in the big scheme of things.

It also reveals how easy it would be to wave all of the African countries’ debt to Western countries. Just £128 spread out over the West. Shoot, that’s the money for just a couple of corporate bailouts.

The U.S. example reveals how costly (just) the Iraq war has been. All of our spending pales in comparison to that expenditure., with the exception of what we have spent bailing out the U.S. economy.

It also reveals that the U.S.’s regular defense budget is almot enough to feed and educate every child on earth for five years, and/or about the same as the revenues of Walmart and Nintendo combined.

If we diverted the money spent on porn, we could save the Amazon… almost five times over. For that matter, if we gave our yoga money to the Amazon, that would just about do it.

Bill Gates could have paid for the Beijing Olympics and had money left over.

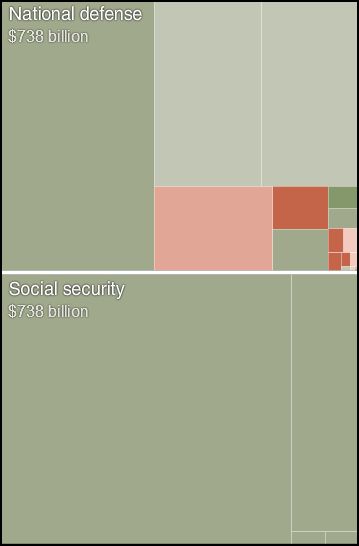

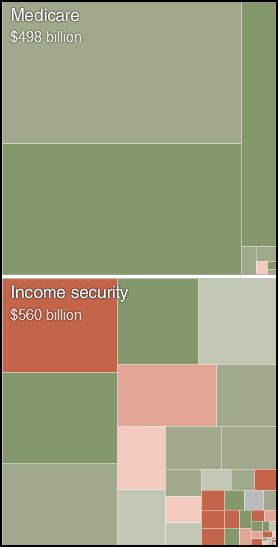

Dmitriy T.M. sent in an interactive breakdown of the US Budget for 2011. In the figures below, the sizes of the squares represent the proportion of the budget, but the colors refer to changes from 2010 (dark and light pink = less funding, dark and light green = more). These figures will give you an idea, but the graphic is interactive and there’s lots more to learn at the site.

See also our posts on how many starving children could be fed by celebrity’s engagement rings and where U.S. tax dollars go.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

American school children learn all about the U.S. gold rush in the Western part of the country. Goldmining was a speculative, but potentially highly rewarding endeavor and attracted, almost exclusively, adult men. But the entrepreneurship of gold mining (though not mining as wage work) is long gone in the U.S. Still, gold is in high demand: “The price of gold, which stood at $271 an ounce on September 10, 2001, hit $1,023 in March 2008, and it may surpass that threshold again” (source). Who are the gold entrepreneurs today? Where? Under what economic conditions do they work? And with what environmental impact?

I found hints to answers in a recent Boston.com slide show and a National Geographic article (thanks to Allison for her tip in the comments). While there is still some gold mining in the U.S., there is gold mining, also, in developing countries and all kinds of people participate:

According to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), there are between 10 million and 15 million so-called artisanal miners around the world, from Mongolia to Brazil. Employing crude methods that have hardly changed in centuries, they produce about 25 percent of the world’s gold and support a total of 100 million people…

Environmentally, gold is especially destructive. The ratio of gold to earth moved is larger than in any other mining endeavor.

It makes me rethink whether I really want to buy gold (because, you know, I do that constantly, darling, constantly). In fact, jewelry accounts for two-thirds of the demand. In the comments, HP reminds me:

Gold (along with even more problematic metals) is found in pretty much all consumer electronics. It’s in your computer, your cellphone, your .mp3 player, your TV/stereo, etc. You’re buying gold all the time already, whether you know it or not.

UPDATE! A reader, Heather Leila, linked to a picture she took of gold prospecting in Suriname (at her own blog). She writes:

The gold mines aren’t what you are thinking. They aren’t underground, you don’t carry a pick axe and a helmet. The garimpos are where the miners have dammed a creek and created large mud pits. The mud is pumped through a long pipe lined with mercury. The mercury attaches itself to the specks of gold and gets filtered out as the mud is poured into a different pit. The mercury is then burned off, while the gold remains. This is how it was explained to me. From the plane, they are exposed patches of yellow earth dotting the endless forest.

See also our posts on post-oil boom life and gorgeous photos of resource extraction by Edward Burtynsky.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

The images below are aerial shots of a development in California City, a city about 100 miles northeast of L.A. The development was abandoned before being built, leaving a grid of empty streets now visible on Google maps:

California City was planned in the late 1950s and early 1960s when L.A. was experiencing a major boom and houses were increasingly being built in large, pre-planned developments by a single construction firm. Instead of building houses as people requested them, the new business model was to buy a large section of property, build a lot of houses in more of an assembly-line fashion, and then find buyers for them and, with the post-World War II economic boom and subsequent suburban flight, it worked.

But as these maps testify, sometimes things go awry; a particular city doesn’t grow as much as the developers thought (California City was supposed to rival L.A. in size), or an economic downturn affects the real estate market in a more widespread manner (see the comments for several readers’ summaries of the many factors that have at times played into real estate booms and busts, including policy decisions in both the public and private sectors). And with the planned development housing model, we may be left not with a few unsold houses, but with bizarre ghost towns in varying stages of completion as evidence.

Related posts: the dilemma of the duplex, Michigan and the recession, and economic change hits the mall.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

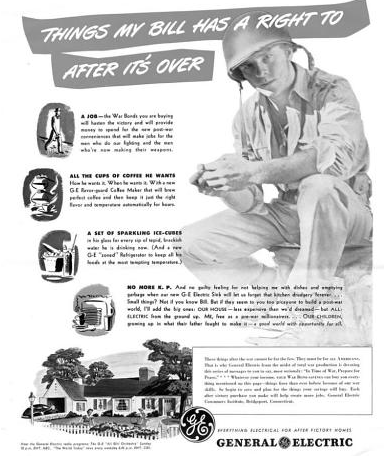

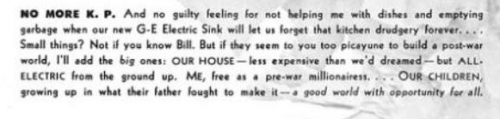

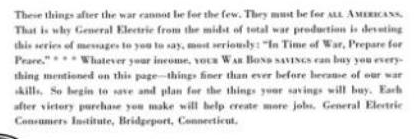

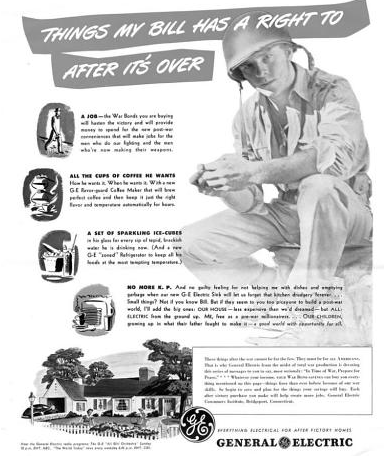

In Sold American: Consumption and Citizenship, 1890-1945, Charles McGovern discusses how, during World War II, advertisers tried to link “…consumption, war, and the deepest American political ideals…in a new blend of political ideology, corporate interest, and private appeal” (p. 353). That is, a company’s contribute to the war effort would be emphasized while the non-war-related products it sold would be offered up as the reward waiting Americans once the war was won. The ability to consume products becomes, then, one of the things American soldiers are fighting for as well as what they are owed upon their return home.

This G.E. ad presents this message blatantly, turning G.E. consumer products into “rights” (larger images of parts of the text below or available here):

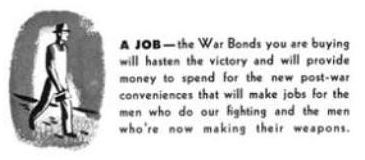

Enlarged text:

Notice that, first, women who were making weapons (and other items) in factories during WWII are ignored here–they certainly didn’t have the right to a job, as many learned when they were forced to leave their jobs so that returning soldiers could have them. Also notice that consumption is patriotic–by purchasing G.E. products, you’ll be making sure the men who did “our fighting” have jobs afterward.

Another section from the ad:

“K.P.” means “kitchen patrol.” Once he returns home, a soldier has the right to avoid housework and not even feel bad about it; that is, he is owed a gendered division of labor. Luckily, G.E. has a product that will allow him to exercise that right and reduce the burden of housework on his wife (and, as the ad says in another section, G.E. can ensure his right to coffee whenever he wants it with an electric coffee maker).

The section of text at the bottom of the ad makes the connection between patriotism, consumption, and war victory extremely clear:

Text:

These things after the war cannot be for the few. The must be for ALL AMERICANS. That is why General Electric from the midst of total war production is devoting this series of messages to you to say, most seriously: “In Time of War, Prepare for Peace.” Whatever your income, YOUR WAR BOND SAVINGS can buy you everything mentioned on this page-things finer than ever before because of our war skills. So begin to save and plan for the things your savings will buy. Each after victory purchase you make will help create more jobs. Gender Electric Consumers Institute, Bridgeport, Connecticut.

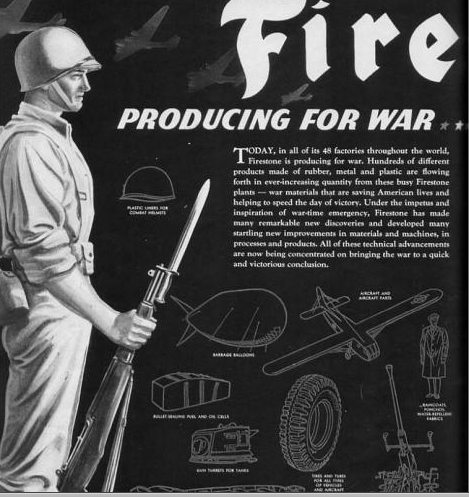

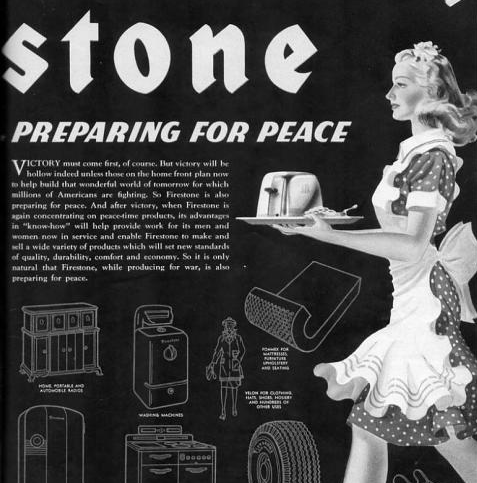

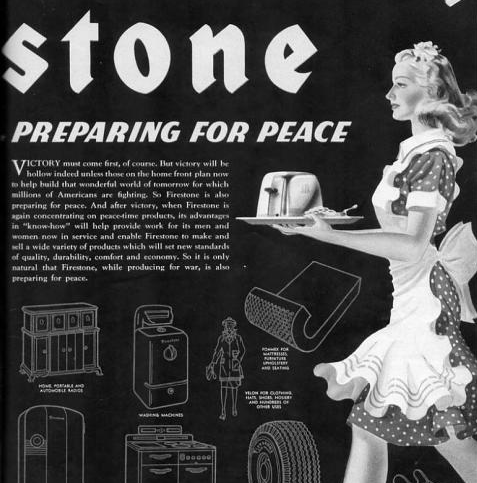

A two-page Firestone ad contains the same elements: post-war consumption as a reward for victory, and a gendered division of the companies products into the masculinized war effort and the feminized post-war consumerism that Americans could look forward to:

Text:

Today, in all of its 48 factories throughout the world, Firestone is producing for war. Hundreds of different products made of rubber, metal and plastic are flowing forth in ever-increasing quantity from these busy Firestone plants–war materials that are saving American lives and helping to speed the day of victory. Under the impetus and inspiration of war-time emergency, Firestone has made many remarkable new discoveries and developed many startling new improvements in materials and machines, in processes and products. All of these technical advancements are now being concentrated on bringing the war to a quick and victorious conclusion.

Text:

Victory must come first, of course. But victory will be hollow indeed unless those on the home front plan now to help build that wonderful world of tomorrow for which millions of Americans are fighting. So Firestone is also preparing for peace. And after victory, when Firestone is again concentrating on peace-time products, its advantages in “know-how” will help provide work for its men and women now in service and enable Firestone to make and sell a wide variety of products which will set new standards of quality, durability, comfort and economy. So it is only natural that Firestone, while producing for war, is also preparing for peace.

It’s similar to President Bush’s post-9/11 suggestion that Americans who want to do something for their country should go shopping, since that would help the economy.

UPDATE: Reader AR says,

Bush’s suggestion is based on the Keynesian idea that consumption drives wealth creation, while these ads are promoting the older idea that saving, accepting hard times now for greater consumption later, is the path to wealth. Indeed, what many viewed as the “point” of the war is basically the same as the mentality behind savings in general: biting the bullet now for prosperity latter, and for future generations. This site itself has featured many ads encouraging people to reduce consumption as much as possible, and to save in the form of war bonds.

Can anyone seriously imagine seeing the line in the GE ad, “So begin to save and plan for the things your savings will buy,” in any modern advertisement?

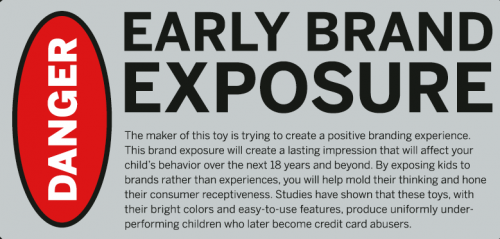

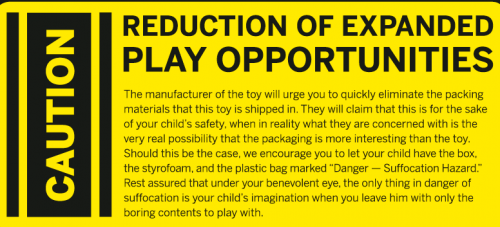

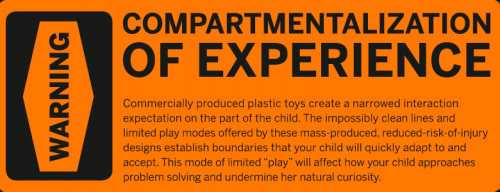

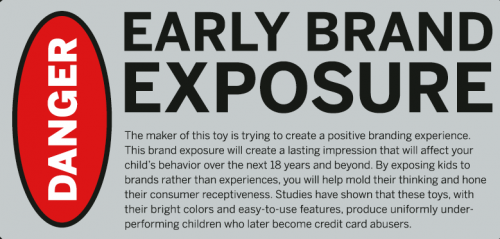

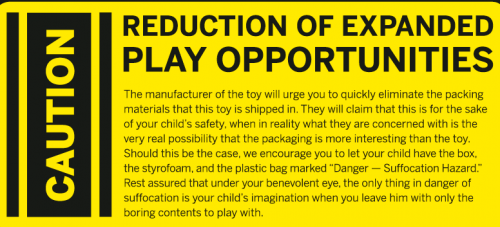

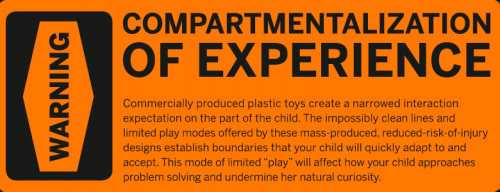

Joshua B. (of Jack-Booted Liberal) let us know about a post at Make about alternative toy warning labels they’d like to see. Dale Dougherty says,

…American kids are raised in an overly cautious manner, out of fear that they might get hurt, and we are limiting their ability to explore a wider range of experience.

The proposed warning labels:

The labels highlight the fact that we worry about some threats to children but not others, and also the way that the potential dangers of toys are often exaggerated (“Studies have shown that these toys…produce uniformly underperforming children who later become credit card abusers.”).

Not that I advocate letting your kid play with a plastic bag. But a giant appliance box with some catalogs to cut pictures out of and glue on as decoration? Best. Toy. Ever.

Also check out our post on the commercialization of childhood.

Dmitriy T.M. sent in this video about the production and marketing of bottled water. It’s a little over-the-top at the beginning, but it brings up a lot of really interesting issues surrounding the selling of a product that is, in the U.S., available to the vast majority of people at a much cheaper price in their kitchen. And yes, I know, some people’s water tastes terrible, etc. etc. The point, in general, still stands that we are spending a lot of money and resources carting water around, and I find the advertising for bottled water fascinating.

Also see The Story of Stuff.

Since I’ve been obsessed in recent months with marketing techniques and the social psychology of shopping, Dmitriy T.M. sent me a video found at Time; in the video Martin Lindstrom argues that sound can be used to encourage shoppers to buy more items.

So if you need to increase sales in your store, get a bunch of babies and have them sitting around giggling. You don’t even have to pay sound licensing fees!

NOTE: I see that a lot of commenters are discussing their personal lack of reaction to the sound of giggling babies, etc. I totally get it–I raised an eyebrow as well. But we should keep in mind that there may be a difference between actively reacting to something or caring about it greatly (say, loving kids) and being indirectly influenced by sounds that might vaguely evoke some element of it. Of course, from the video we don’t know if any business has actually been successful at getting people to buy things by using sounds similar to babies giggling (or water being poured), only that people seem to react positively to those sounds in the lab. So I don’t know how much legitimacy there is to this, but I know marketers have definitely tried to use smells to influence people to linger in an area, hopefully then leading to higher sales.

Other posts on marketing and psychology: restaurant menus and the meaningless discount.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Katrin sent along links to visual portrayals of how much money goes, or could go, to various causes. While sometimes it’s hard to comprehend what a billion, or 300 billion, dollars amounts to, these images give us perspective on just where our priorities lie. The segments below are clipped from the visuals for the U.K. and the U.S. at Information is Beautiful.

The British example nicely illustrates how little social services like education, police, and welfare cost in the big scheme of things.

It also reveals how easy it would be to wave all of the African countries’ debt to Western countries. Just £128 spread out over the West. Shoot, that’s the money for just a couple of corporate bailouts.

The U.S. example reveals how costly (just) the Iraq war has been. All of our spending pales in comparison to that expenditure., with the exception of what we have spent bailing out the U.S. economy.

It also reveals that the U.S.’s regular defense budget is almot enough to feed and educate every child on earth for five years, and/or about the same as the revenues of Walmart and Nintendo combined.

If we diverted the money spent on porn, we could save the Amazon… almost five times over. For that matter, if we gave our yoga money to the Amazon, that would just about do it.

Bill Gates could have paid for the Beijing Olympics and had money left over.

Dmitriy T.M. sent in an interactive breakdown of the US Budget for 2011. In the figures below, the sizes of the squares represent the proportion of the budget, but the colors refer to changes from 2010 (dark and light pink = less funding, dark and light green = more). These figures will give you an idea, but the graphic is interactive and there’s lots more to learn at the site.

See also our posts on how many starving children could be fed by celebrity’s engagement rings and where U.S. tax dollars go.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

American school children learn all about the U.S. gold rush in the Western part of the country. Goldmining was a speculative, but potentially highly rewarding endeavor and attracted, almost exclusively, adult men. But the entrepreneurship of gold mining (though not mining as wage work) is long gone in the U.S. Still, gold is in high demand: “The price of gold, which stood at $271 an ounce on September 10, 2001, hit $1,023 in March 2008, and it may surpass that threshold again” (source). Who are the gold entrepreneurs today? Where? Under what economic conditions do they work? And with what environmental impact?

I found hints to answers in a recent Boston.com slide show and a National Geographic article (thanks to Allison for her tip in the comments). While there is still some gold mining in the U.S., there is gold mining, also, in developing countries and all kinds of people participate:

According to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), there are between 10 million and 15 million so-called artisanal miners around the world, from Mongolia to Brazil. Employing crude methods that have hardly changed in centuries, they produce about 25 percent of the world’s gold and support a total of 100 million people…

Environmentally, gold is especially destructive. The ratio of gold to earth moved is larger than in any other mining endeavor.

It makes me rethink whether I really want to buy gold (because, you know, I do that constantly, darling, constantly). In fact, jewelry accounts for two-thirds of the demand. In the comments, HP reminds me:

Gold (along with even more problematic metals) is found in pretty much all consumer electronics. It’s in your computer, your cellphone, your .mp3 player, your TV/stereo, etc. You’re buying gold all the time already, whether you know it or not.

UPDATE! A reader, Heather Leila, linked to a picture she took of gold prospecting in Suriname (at her own blog). She writes:

The gold mines aren’t what you are thinking. They aren’t underground, you don’t carry a pick axe and a helmet. The garimpos are where the miners have dammed a creek and created large mud pits. The mud is pumped through a long pipe lined with mercury. The mercury attaches itself to the specks of gold and gets filtered out as the mud is poured into a different pit. The mercury is then burned off, while the gold remains. This is how it was explained to me. From the plane, they are exposed patches of yellow earth dotting the endless forest.

See also our posts on post-oil boom life and gorgeous photos of resource extraction by Edward Burtynsky.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

The images below are aerial shots of a development in California City, a city about 100 miles northeast of L.A. The development was abandoned before being built, leaving a grid of empty streets now visible on Google maps:

California City was planned in the late 1950s and early 1960s when L.A. was experiencing a major boom and houses were increasingly being built in large, pre-planned developments by a single construction firm. Instead of building houses as people requested them, the new business model was to buy a large section of property, build a lot of houses in more of an assembly-line fashion, and then find buyers for them and, with the post-World War II economic boom and subsequent suburban flight, it worked.

But as these maps testify, sometimes things go awry; a particular city doesn’t grow as much as the developers thought (California City was supposed to rival L.A. in size), or an economic downturn affects the real estate market in a more widespread manner (see the comments for several readers’ summaries of the many factors that have at times played into real estate booms and busts, including policy decisions in both the public and private sectors). And with the planned development housing model, we may be left not with a few unsold houses, but with bizarre ghost towns in varying stages of completion as evidence.

Related posts: the dilemma of the duplex, Michigan and the recession, and economic change hits the mall.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

In Sold American: Consumption and Citizenship, 1890-1945, Charles McGovern discusses how, during World War II, advertisers tried to link “…consumption, war, and the deepest American political ideals…in a new blend of political ideology, corporate interest, and private appeal” (p. 353). That is, a company’s contribute to the war effort would be emphasized while the non-war-related products it sold would be offered up as the reward waiting Americans once the war was won. The ability to consume products becomes, then, one of the things American soldiers are fighting for as well as what they are owed upon their return home.

This G.E. ad presents this message blatantly, turning G.E. consumer products into “rights” (larger images of parts of the text below or available here):

Enlarged text:

Notice that, first, women who were making weapons (and other items) in factories during WWII are ignored here–they certainly didn’t have the right to a job, as many learned when they were forced to leave their jobs so that returning soldiers could have them. Also notice that consumption is patriotic–by purchasing G.E. products, you’ll be making sure the men who did “our fighting” have jobs afterward.

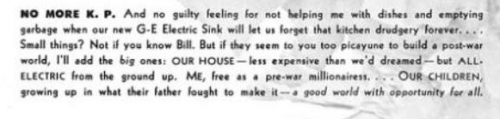

Another section from the ad:

“K.P.” means “kitchen patrol.” Once he returns home, a soldier has the right to avoid housework and not even feel bad about it; that is, he is owed a gendered division of labor. Luckily, G.E. has a product that will allow him to exercise that right and reduce the burden of housework on his wife (and, as the ad says in another section, G.E. can ensure his right to coffee whenever he wants it with an electric coffee maker).

The section of text at the bottom of the ad makes the connection between patriotism, consumption, and war victory extremely clear:

Text:

These things after the war cannot be for the few. The must be for ALL AMERICANS. That is why General Electric from the midst of total war production is devoting this series of messages to you to say, most seriously: “In Time of War, Prepare for Peace.” Whatever your income, YOUR WAR BOND SAVINGS can buy you everything mentioned on this page-things finer than ever before because of our war skills. So begin to save and plan for the things your savings will buy. Each after victory purchase you make will help create more jobs. Gender Electric Consumers Institute, Bridgeport, Connecticut.

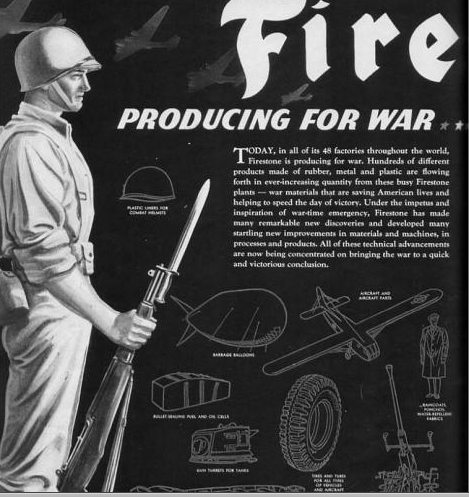

A two-page Firestone ad contains the same elements: post-war consumption as a reward for victory, and a gendered division of the companies products into the masculinized war effort and the feminized post-war consumerism that Americans could look forward to:

Text:

Today, in all of its 48 factories throughout the world, Firestone is producing for war. Hundreds of different products made of rubber, metal and plastic are flowing forth in ever-increasing quantity from these busy Firestone plants–war materials that are saving American lives and helping to speed the day of victory. Under the impetus and inspiration of war-time emergency, Firestone has made many remarkable new discoveries and developed many startling new improvements in materials and machines, in processes and products. All of these technical advancements are now being concentrated on bringing the war to a quick and victorious conclusion.

Text:

Victory must come first, of course. But victory will be hollow indeed unless those on the home front plan now to help build that wonderful world of tomorrow for which millions of Americans are fighting. So Firestone is also preparing for peace. And after victory, when Firestone is again concentrating on peace-time products, its advantages in “know-how” will help provide work for its men and women now in service and enable Firestone to make and sell a wide variety of products which will set new standards of quality, durability, comfort and economy. So it is only natural that Firestone, while producing for war, is also preparing for peace.

It’s similar to President Bush’s post-9/11 suggestion that Americans who want to do something for their country should go shopping, since that would help the economy.

UPDATE: Reader AR says,

Bush’s suggestion is based on the Keynesian idea that consumption drives wealth creation, while these ads are promoting the older idea that saving, accepting hard times now for greater consumption later, is the path to wealth. Indeed, what many viewed as the “point” of the war is basically the same as the mentality behind savings in general: biting the bullet now for prosperity latter, and for future generations. This site itself has featured many ads encouraging people to reduce consumption as much as possible, and to save in the form of war bonds.

Can anyone seriously imagine seeing the line in the GE ad, “So begin to save and plan for the things your savings will buy,” in any modern advertisement?

Joshua B. (of Jack-Booted Liberal) let us know about a post at Make about alternative toy warning labels they’d like to see. Dale Dougherty says,

…American kids are raised in an overly cautious manner, out of fear that they might get hurt, and we are limiting their ability to explore a wider range of experience.

The proposed warning labels:

The labels highlight the fact that we worry about some threats to children but not others, and also the way that the potential dangers of toys are often exaggerated (“Studies have shown that these toys…produce uniformly underperforming children who later become credit card abusers.”).

Not that I advocate letting your kid play with a plastic bag. But a giant appliance box with some catalogs to cut pictures out of and glue on as decoration? Best. Toy. Ever.

Also check out our post on the commercialization of childhood.