Commodification is the process by which something that is not bought and sold becomes bought and sold. At one time, Americans grew, or raised and butchered, much of their own food. Later, meat, grains, and vegetables became commodified. Instead of working in the fields and with their animals, people would “go to work,” earn a new thing called a “wage,” and trade it for meat, grains, and vegetables. With those raw ingredients, they would prepare a meal.

More recently in American history, the very preparation of food has commodified as well. When I go to a restaurant, I am exchanging my wage for the planting, harvesting, processing, delivering, preparing, and disposal/clean up of my meal. In this way, then, more and more components of our daily nutritional intake have become commodified.

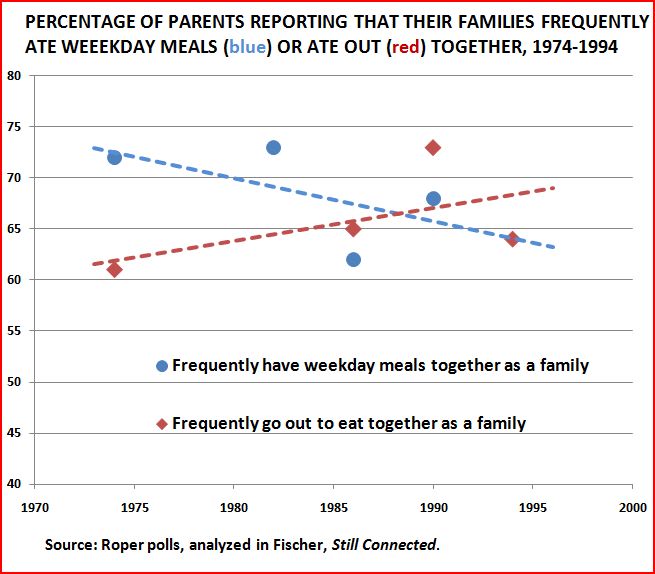

The graph below traces the increasing commodification of “dinner.” When it comes to family dinners, Americans are increasingly turning to restaurants, which commodify the preparation of food and the post-meal chores. Sometime around 1988, the family dinner as a commodity became more common than family dinners at home.

Image borrowed from Claude Fischer’s Made in America.

UPDATE: In the comments, Ludvig von Mises offers this alternative explanation:

Another way to look at this would be as a form of increasing wealth. The nobility of old, after all, also did not butcher, harvest, and prepare their own meals, and neither did the wealthiest members of the new rich. Over time, the ability to afford such a thing on a more regular basis has gradually expanded to more and more people.

Matter of fact, there is very little in the way of such luxury that has been enjoyed by the elites of the past that is not available to the majority of workers today. “Commodification” is not, as you suggest, the creation of any kind of new product, but merely of making extremely expensive products affordable to a much larger fraction of the population.

“The characteristic feature of modern capitalism is mass production of goods destined for consumption by the masses.”

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.