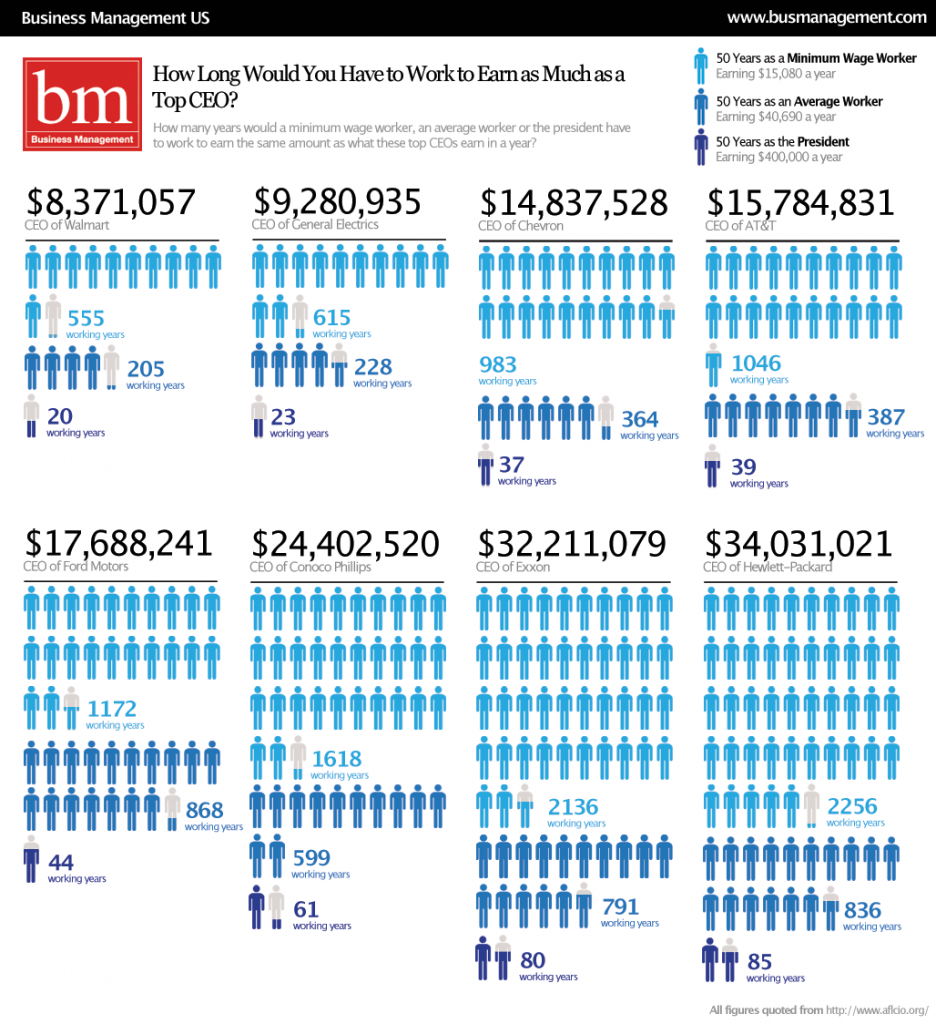

Business Management offers this great visual for understanding income in equality in the U.S. Each light blue figure in this visual represents 50 years of work at minimum wage (making $15,080 a year); the medium blue figures represent 50 years of work at the average wage (making $40,690 a year); the dark blue figures represent 50 years as the President of the United States (making $400,000 a year).

Let’s take the most dramatic example, just for fun: Hewlett-Packard.

A minimum wage worker would have to work for 2,256 years to make what what the CEO of Hewlett-Packard makes in a year.

The average worker would have to work 836 years to match his yearly salary.

And Barack Obama would have to President for 85 years before he made what the CEO of Hewlett-Packard makes in one year.

See other posts on income inequality here, here, here, here, and here.

Via Chartporn.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.