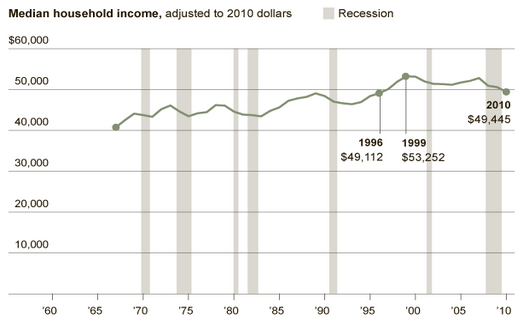

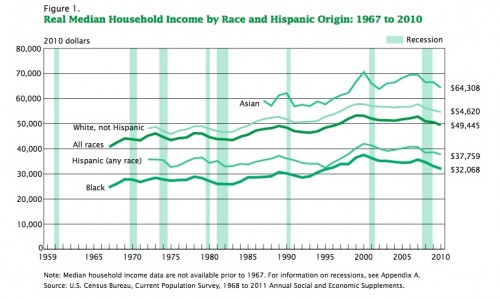

The Census Bureau just published new data revealing trends in living standards as of 2010. The trends are troubling to say the least. Median household income (adjusted for inflation) fell to $49,445. That means that the median household now earns less than it did a decade ago. This marks the first decade since the Great Depression without an increase in real median income.

According to Lawrence Katz, a labor expert and Harvard economist:

This is truly a lost decade. We think of America as a place where every generation is doing better, but we’re looking at a period when the median family is in worse shape than it was in the late 1990s.

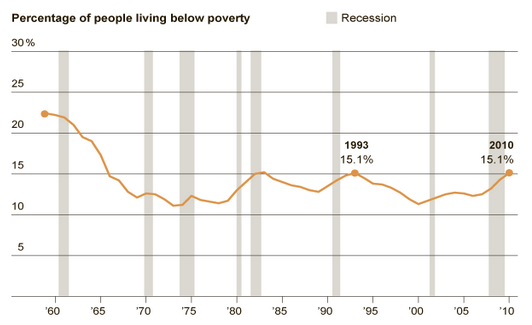

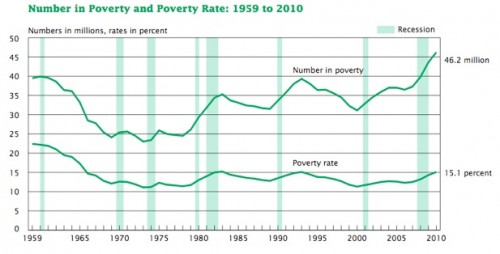

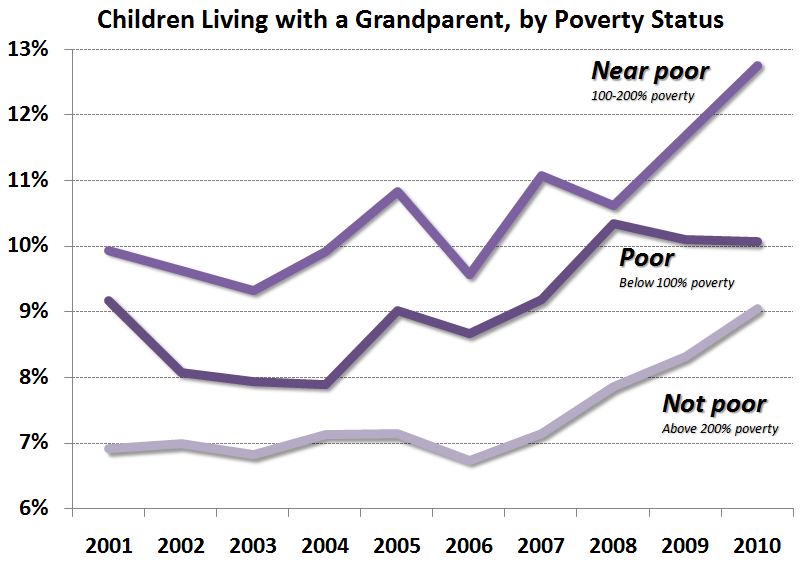

The percentage of Americans living in poverty hit 15.1 percent, the highest percentage since 1993. There are now 46.2 million people living below the poverty line, the greatest number ever recorded by the Census Bureau. Child poverty stood at 22 percent.

Things are unlikely to get better this year. State and local governments are slashing employment and programs and the federal government is now moving into cutting mode itself.

This depressing situation is not simply a recession phenomenon. As the New York Times reports, the expansion period of 2001 to 2007 “was the first… on record where the level of poverty was deeper, and median income of working-age people was lower, at the end than at the beginning.”

Of course, while the great majority of people are struggling, a small minority have been doing very well. One consequence, as the chart below highlights, is a strong growth in inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient with higher numbers reflecting greater inequality). As I noted in a previous post, over the years 2002 to 2007, the top 1% of households captured 58% of all the income generated.

In brief, there is a small minority that is doing very well and a great majority that is struggling, with a significant number in free fall.