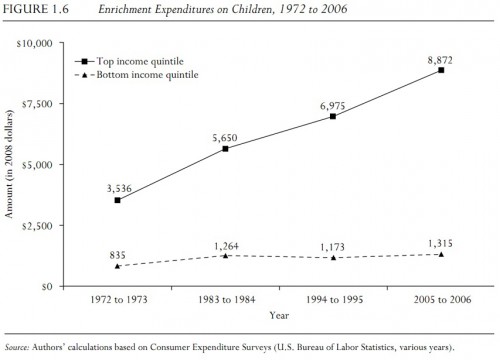

Technically yesterday was tax day, but since it fell on a weekend and today is a holiday in Washington, D.C. (Emancipation Day), Americans actually got two extra days to file. Whether you’re already done or are wildly rushing to finish up, you might enjoy this short video by political economist Robert Reich, explaining how the concentration of wealth, and the ability of the very wealthy to redesign the tax code to their advantage have affected the overall economy:

Via The Sociology Cinema.