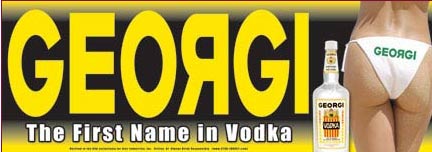

Angela Zhang sent in a Heineken commercial that helpfully illustrates the common depiction of sex and dating as a game or hunt, and alcohol as a tool in that hunt. In the commercial, men are predators in a sexual “jungle,” and attractive women are their “prey.” The true champion in this hunt will not just manage to get his prey — he’ll get her to “surrender” to him voluntarily:

It’s not the first time Heineken has presented itself as a useful tool for your dating life. Also check out this video on women in beer ads. Of course, other times beer ads conflate women’s bodies with beer itself. Or liquor as the response to the loss of patriarchal power. And hey, guys, if you fail in your hunt, don’t worry — it turns out alcohol is better than relationships with women anyway!