“Next to being a Hollywood movie star, nothing was more glamorous.” This breathless statement, quoted in Femininity in Flight, was uttered by a flight attendant in 1945. At the time being a stewardess was quite glamorous. Like motion pictures do today, airlines trafficked in “the business of female spectacle.” They hired only women who they believed to represent ideal femininity. Chosen for their beauty and poise, and only from among the educated, and slender, they were as much of an icon as Miss America. And they were almost all White.

Victoria Vantoch tells the story of the first African American flight attendants in a chapter of her new book, The Jet Sex. Patricia Banks was one of the first Black women to sue an airline for racial discrimination. She graduated from flight attendant training school at the top of her class and applied to several airlines. But it was 1956 and the U.S. airlines had never hired a Black woman. After 10 months of trying, an airline recruiter pulled her aside and admitted that it was because of her race. Which, of course, it was; airlines disqualified any applicants that had broad noses, full lips, coarse hair, or a “hook nose” (to weed out Jews).

Banks sued. After four years of litigation, Capital Airlines was forced to hire her. She postponed her marriage and took the job (airlines only hired single women as flight attendants). When she put on her uniform for the first time, she said:

After all I had gone through, I couldn’t believe I was finally wearing the uniform. I had made it. I was going to fly. It was such an accomplishment.

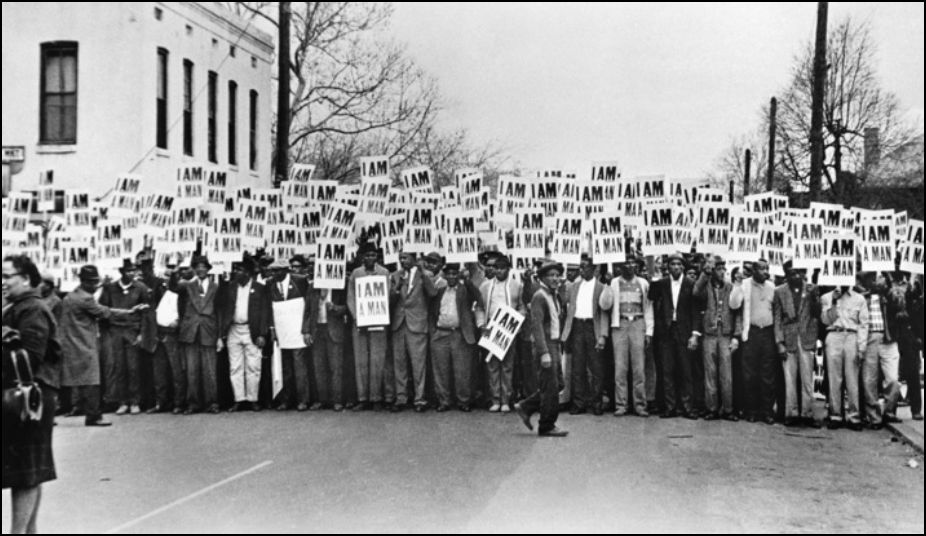

Individual women weren’t the only ones pushing to integrate the flight attendants corps. International surveys showed that citizens of other countries knew that America had a “race problem” and this was a problem for then-President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson. They needed to do something flashy and they turned to flight attendants to do it. If they could make Black women the face of such an iconic and high-profile occupation, they thought, it would help restore America’s reputation. According to Vantoch, Johnson “made stewardess integration his personal cause.”

That was 1961; in 1964 Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act mandating equal treatment in the workplace. The following year, in response to even more lawsuits, approximately 50 Black women were hired by airlines. This would make them 0.33% of the workforce.

Patricia Banks and her fellow first African American flight attendants, including Mary Tiller and Marlene White, would continue to face racism, now from co-workers, passengers, and supervisors. Banks would quit after one year, citing exhaustion in the face of emotionally draining feminine work and a constant onslaught of racism. She was a great flight attendant, though, and proud to show the world that a Black woman could shine in the occupation.

Here’s Patricia Banks, telling the story in her own words at Black History in Aviation. It’s worth a watch; she’s amazing:

Cross-posted at VitaminW and Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.