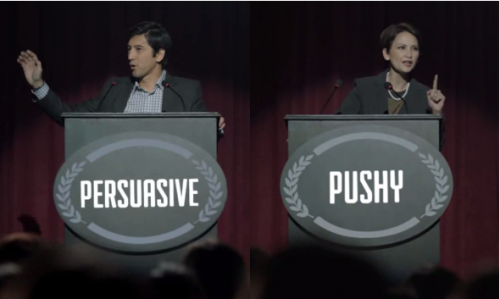

This 1 minute commercial for Pantene, running in the Philippines, is getting a lot of praise. It does a powerful job of pointing out the way that women are disadvantaged in corporate contexts. The men and women in the ad are portrayed similarly, but the women are judged for the behavior while the men are praised.

But then the end. Oh Pantene. The answer to this systemic double bind that damns women if they do and damns them if they don’t is, apparently, to “be strong and shine.”

I suppose we shouldn’t expect much more from a shampoo ad, but I lament the ending anyway. It resonates with a wider cultural trend in which feminist empowerment has been conflated with individual gain within a patriarchal system, not a collective effort to end patriarchy once and for all.

This is the lesson of Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In: the system’s all set up to fuck you over, she acknowledges, but then she whispers: I will try to help you get to the top anyway. No matter if you have to step all over lots of other women on the way. That’s not feminism, that’s self-interest. And it’s certainly not progressive change.

Thanks to @yassmin_a at Redefining the Narrative, Keely W., and Jacob R. for the link! Cross-posted at the Huffington Post.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.