We often think that religion helps to build a strong society, in part because it gives people a shared set of beliefs that fosters trust. When you know what your neighbors think about right and wrong, it is easier to assume they are trustworthy people. The problem is that this logic focuses on trustworthy individuals, while social scientists often think about the relationship between religion and trust in terms of social structure and context.

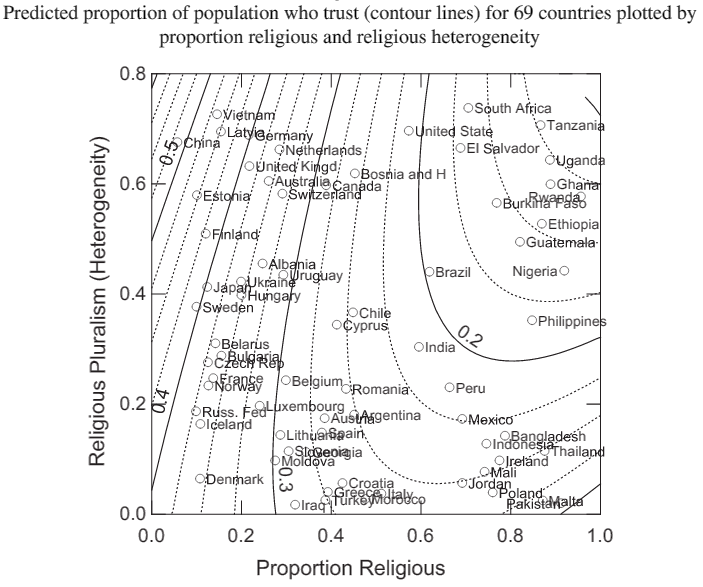

New research from David Olson and Miao Li (using data from the World Values survey) examines the trust levels of 77,405 individuals from 69 countries collected between 1999 and 2010. The authors’ analysis focuses on a simple survey question about whether respondents felt they could, in general, trust other people. The authors were especially interested in how religiosity at the national level affected this trust, measuring it in two ways: the percentage of the population that regularly attended religious services and the level of religious diversity in the nation.

These two measures of religious strength and diversity in the social context brought out a surprising pattern. Nations with high religious diversity and high religious attendance had respondents who were significantly less likely to say they could generally trust other people. Conversely, nations with high religious diversity, but relatively low levels of participation, had respondents who were more likely to say they could generally trust other people.

One possible explanation for these two findings is that it is harder to navigate competing claims about truth and moral authority in a society when the stakes are high and everyone cares a lot about the answers, but also much easier to learn to trust others when living in a diverse society where the stakes for that difference are low. The most important lesson from this work, however, may be that the positive effects we usually attribute to cultural systems like religion are not guaranteed; things can turn out quite differently depending on the way religion is embedded in social context.

Evan Stewart is a PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota studying political culture. He is also a member of The Society Pages’ graduate student board. There, he writes for the blog Discoveries, where this post originally appeared. You can follow him on Twitter.