For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2012.

In Counted Out: Same-Sex Relations and Americans’ Definitions of Family, released last month, authors Brian Powell, Catherine Bolzendahl, Claudia Geist, and Lala Carr Steelman look at how Americans conceptualize “the family” — that is, not what they think about their own families, but what they think counts as a family. Which groups or living arrangements do they include in the definition of “family,” and who is excluded?

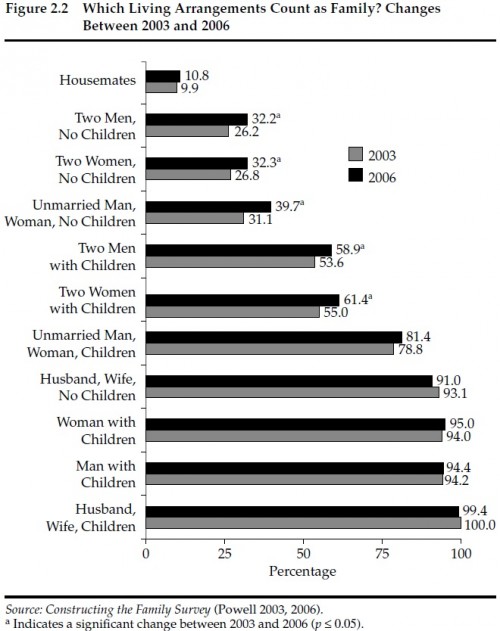

Based on surveys conducted in 2003 and 2006, Americans still hold the stereotypical nuclear family (husband, wife, kids) as the gold standard — virtually everyone agrees that such a group counts as a family. Being legally married, or the presence of children, generally leads to acceptance of a grouping as a family — the overwhelming majority believed single parents and their children count as families, as do married heterosexual couples without kids, and even unmarried heterosexual couples who have children. But when couples are same-sex, or don’t have kids, Americans are much less certain that they can qualify as a family. In 2006, the percent of respondents believing gay or lesbian couples with kids are families was notably smaller than for those agreeing that single parents or straight couples count, though it had increased since 2003:

And notice the importance of children to definitions of family — only a minority of respondents thought that gay, lesbian, or straight couples without kids are a family.

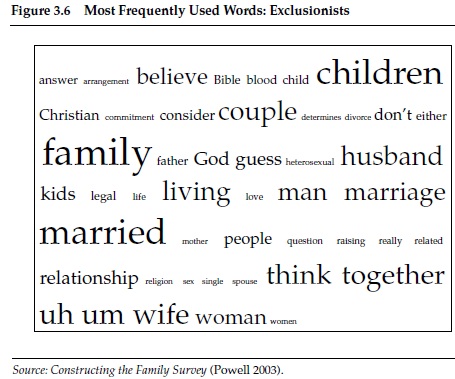

The authors divided respondents into three groups, based on their answers: exclusionists (those with the most restrictive definitions of family), moderates, and inclusionists (those with the most expansive definitions). Looking at the words these groups used as the talked about their characterizations of family, we see clear differences. The words used most frequently by exclusionists highlight the centrality of marriage, as well as an emphasis on what type of people constitute a family (husband, wife, woman, man), and the explicit inclusion of religious-based elements in their ideas of what makes a family:

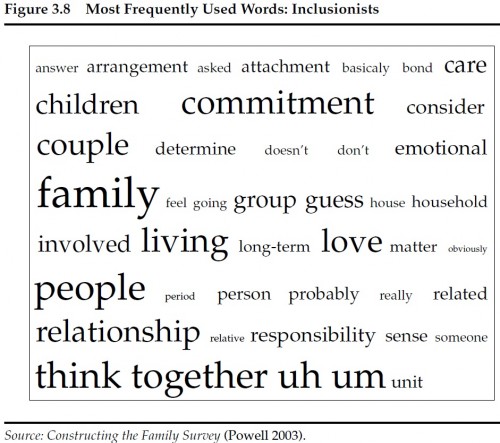

The language used by inclusionists emphasized emotional attachments rather than the legal institution of marriage as the basis for determining what counts as a family:

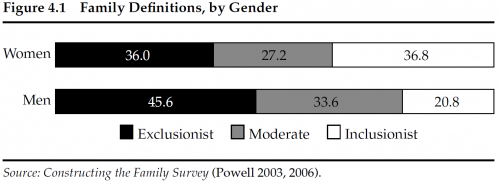

Women were more inclusive than men, in general:

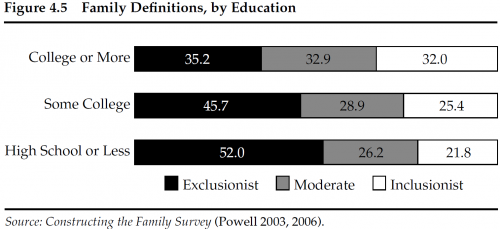

The more educated respondents were, the more inclusive their definitions of family tended to be:

The Russell Sage Foundation released these and many other charts and tables from the book, so it’s definitely worth a look if you’re interested in how Americans think about the family. Overall, the authors found that definitions of the family were becoming more inclusive. Presumably this trend has continued and even accelerated since the 2006 survey, given how attitudes have shifted on a number of issues involving gay and lesbian rights in the past few years.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.