It’s that time of year again! Fans across the nation are coming together to cheer on their colleges and universities in cutthroat competition. The drama is high and full of surprises as underdogs take on the established greats—some could even call it madness.

I’m talking, of course, about The International Championship of Collegiate A Cappella.

In case you missed the Pitch Perfect phenomenon, college a cappella has come a long way from the dulcet tones of Whiffenpoofs in the West Wing. Today, bands of eager singers are turning pop hits on their heads. Here’s a sampler, best enjoyed with headphones:

And competitive a cappella has gotten serious. Since its founding in 1996, the ICCA has turned into a massive national competition spawning a separate high school league and an open-entry, international competition for any signing group.

As a sociologist, watching niche hobbies turn into subcultures and subcultures turn into established institutions is fascinating. We even have data! Varsity Vocals publishes the results of each ICCA competition, including the scores and university affiliations of each group placing in the top-three of every quarterfinal, regional semifinal, and national final going back to 2006. I scraped the results from over 1300 placements to see what we can learn when a cappella meets analytics.

Watching a Conference Emerge

Organizational sociologists study how groups develop into functioning formal organizations by turning habits into routines and copying other established institutions. Over time, they watch how behaviors become more bureaucratic and standardized.

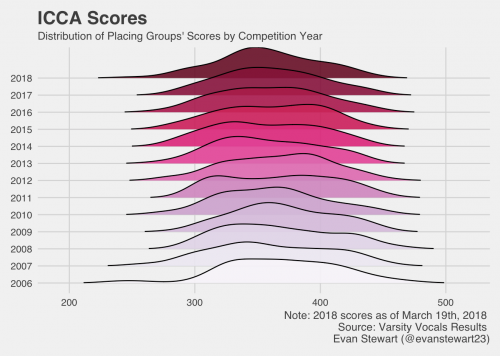

We can watch this happen with the ICCAs. Over the years, Varsity Vocals has established formal scoring guidelines, judging sheets, and practices for standardizing extreme scores. By graphing out the distribution of groups’ scores over the years, you can see the competition get more consistent in its scoring over time. The distributions narrow in range, and they take a more normal shape around about 350 points rather than skewing high or low.

Gender in the A Cappella World

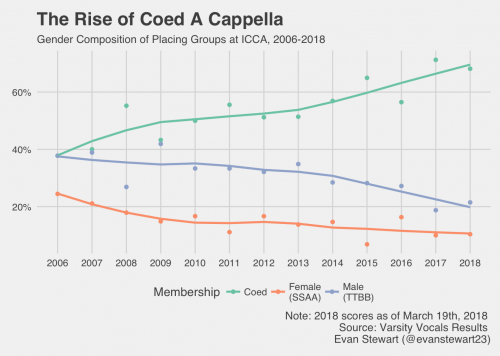

Gender is a big deal in a cappella, because many groups define their membership by gender as a proxy for vocal range. Coed groups get a wider variety of voice parts, making their sound more versatile, but gender-exclusive groups can have an easier time getting a blended, uniform sound. This raises questions about gender and inequality, and there is a pretty big gender gap in who places at competition.

In light of this gap, one interesting trend is the explosion of coed a cappella groups over the past twelve years. These groups now make up a much larger proportion of placements, while all male and all female groups have been on the decline.

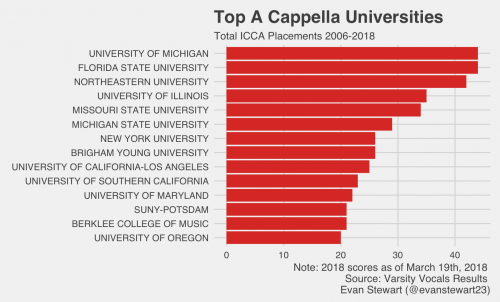

Who Are the Powerhouse Schools?

Just like March Madness, one of my favorite parts about the ICCA is the way it brings together all kinds of students and schools. You’d be surprised by some of the schools that lead on the national scene. Check out some of the top performances on YouTube, and stay tuned to see who takes the championship next month!

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.