Recent reports indicated that FEMA was cutting—and then not cutting—hurricane relief aid to Puerto Rico. When Donald Trump recently slandered Puerto Ricans as lazy and too dependent on aid after Hurricane Maria, Fox News host Tucker Carlson stated that Trump’s criticism could not be racist because “Puerto Rico is 75 percent white, according to the U.S. Census.”

This statement presents racism as a false choice between nonwhite people who experience racism and white people who don’t. It ignores the fact that someone can be classed as white by one organization but treated as non-white by another, due to the way ‘race’ is socially constructed across time, regions and social contexts.

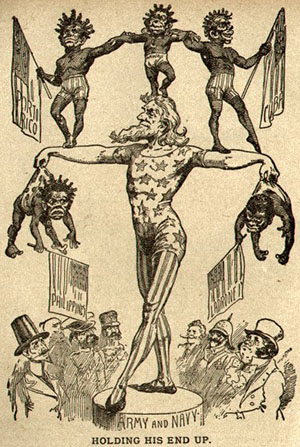

Whiteness for Puerto Ricans is a contradiction. Racial labels that developed in Puerto Rico were much more fluid than on the U.S. mainland, with at least twenty categories. But the island came under U.S. rule at the height of American nativism and biological racism, which relied on a dichotomy between a privileged white race and a stigmatized black one that was designed to protect the privileges of slavery and segregation. So the U.S. portrayed the islanders with racist caricatures in cartoons like this one:

Clara Rodriguez has shown how Puerto Ricans who migrated to the mainland had to conform to this white-black duality that bore no relation to their self-identifications. The Census only gave two options, white or non-white, so respondents who would have identified themselves as “indio, moreno, mulato, prieto, jabao, and the most common term, trigueño (literally, ‘wheat-colored’)” chose white by default, simply to avoid the disadvantage and stigma of being seen as black bodied.

Choosing the white option did not protect Puerto Ricans from discrimination. Those who came to the mainland to work in agriculture found themselves cast as ‘alien labor’ despite their US citizenship. When the federal government gave loans to white home buyers after 1945, Puerto Ricans were usually excluded on zonal grounds, being subjected to ‘redlining’ alongside African Americans. Redlining was also found to be operating on Puerto Rico itself in the insurance market as late as 1998, suggesting it may have even contributed to the destitution faced by islanders after natural disasters.

The racist treatment of Puerto Ricans shows how it is possible to “be white” without white privilege. There have been historical advantages in being “not black” and “not Mexican”, but they have not included the freedom to seek employment, housing and insurance without fear of exclusion or disadvantage. When a hurricane strikes, Puerto Rico finds itself closer to New Orleans than to Florida.

An earlier version of this post appeared at History News Network

Jonathan Harrison, PhD, is an adjunct Professor in Sociology at Florida Gulf Coast University, Florida SouthWestern State College and Hodges University whose PhD was in the field of racism and antisemitism.

Comments 8

Juan Rodriguez — August 4, 2018

I just read this article. It is so full of delusional claims and inaccuracies. I just gonna focus on the biggest mistake here. Lets make sure, you, as a PhD Professor in Sociology understand the gigantic FACT that most Puerto Ricans are WHITES! We are descendants of European immigrants to PR. It is not that we are becoming white or that we look white or that we claim to be white. We are whites. We live in a mostly white island. We have minorities like anywhere else in the Union. So Fox News host Tucker Carlson was 100% accurate and correct. You should know better! You are working in Florida, a state full of white Cubans and white Puerto Ricans and white "latinos".

Benno Medina VonKupferschein — August 4, 2018

Whoaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa....This is my first time to this website, but it will not be my last. I don't even know where to begin with the COLOSSAL ignorance of the implicitly and subtle afro-centric "1-Drop-Rule" stupidity that oozes from every line of this pseudo-sociological clap-trap.

First of all, as someone born and raised in Puerto Rico, I NEVER had to choose my race, my racial reference nor my subsequent racial identity.

I learned it on my WHITE parents', WHITE grand-parents' and WHITE great-grandparents laps. And THEY like me, saw our collective racial context every time we opened our eyes and looked at each other.

NONE of us "thought" we were white, "imagined" we were white or "pretended" we were white just because we MIGRATED to the US...we KNEW it in Puerto Rico and did NOT have to come to the US to "find-out" that we were not white because academic empty-suits who get their insights about Latin American people from the Taco Bell drive-up window menu, typically inhabited by their colluding "peers" like Clara Rodriguez who has made a career of enjoying her white skin while telling the world, "but I just look white".

The problem at the very core of this pseudo-intellectual allegedly "social science" BS is that it labors under the very FALSE, FRAUDULENT and FICTIONAL stereo-typical brainwash that most Americans "experts" who purport to understand the cultures, people and identities of ANYONE from a Latin American which is typically gleaned by their media-informed references of brown Meso-American indigenous ILLEGALS slithering under the US border fences from Mexico or Central or South American contexts, or from episodes of "Modern Family" with Sofia Vergara prancing around with her ass bouncing, her boobies bouncing and speaking (of course) in broken Spanglish 'cause after all "I be's a Latina ju know" while applying brown make-up to her WHITE face...(eye-roll).

The majority of people in both Puerto Rico and Cuba ARE of MAJORITY European contexts, regardless of the absurd nativist nonsense promoted in urban ghettoes in the US about how everyone from specifically the Caribbean islands is really a black person who just "looks white".

Stop and think about this...Would this same "professor" tell Whoopie Goldberg, Oprah or OJ Simpson that they are "really white" but just "look black"??? Of course not. Why? Because these incompetent and inadequate "scholars" who make their lives jumping in and out of the "diversity" and "multi-culti-mumbo-jumbo" rabbit-holes on campuses from Florida to California to Massachusetts and back to Florida, on campuses that are not exactly known for their intellectual "high-bar" support their nonsense for fear of being accused of the "R" word and therein lies the tacit permission to allow 3rd rate FAKE "scholarship" these idiots pose as "informed", "insightful" or otherwise "intelligent" discourse.

Unfortunately, dullards of this magnitude ESPECIALLY in the realm of "mushy" disciplines like the "sociology" find a very fertile field in which to lay their putrid turds for others to munch on.

Sad from any angle...really sad. Meanwhile WHITES from Puerto Rico, Cuba or any other Latin American contexts will live their lives free of the contrived, contorted and confused FAKE "premises" of these bumbling academic buffoons.

As my Basque-descended grand father used to say regularly...."mi'jo cuando el hombre pierde la verguenza nadie se la devuelve"

I would strongly suggest the "authors" of the afro-centric RACIST nonsense look for their "verguenza" but they will never find it in the American academy...NEVER!

Olga M. — March 11, 2019

Both of these comments are based on ignorance and lack of Knowledgeable about the history and experiences of the Puerto Rican people. Puerto Ricans are a blended culture that originated in indigenous culture. When the Spaniards conquered Puerto Rico they brought African slaves to the island and thus this blending resulted in A diverse Puerto Rican culture: very dark very light complexion. Dark skinned Puerto Rican’s get treated very differently than light skin Puerto Ricans not just in Puerto Rico but in the United States as well. In summary Puerto Ricans are not white people But rather a blending of Spanish, indigenous, and African heritage.

Heghmard Wellie — March 22, 2021

There are very few white people in the world who face racism because every one targets black people. It is not their own fault to be black because it is not in their own hands. Everyone should be treated equally so that we can make this planet peaceful for everyone. I am writing an essay to spread awareness about this matter with the help of writing an essay website which I hired after reading reviews about it at essayyoda.com source because it shares real and honest reviews with us, unlike any other source.

dsbbe — February 10, 2022

This is an article that shows reasonable and accurate judgment. Anyone interested in this area will agree with you.

토토

totoguy — December 6, 2022

Wow, what is this? This post made me think a lot for a while, and I think a lot of people should read this comment, but I think it's a waste. 토토사이트

totovi — December 6, 2022

I think your writing is the best I've ever seen. It's a very interesting and touching article. Thanks to your writing, I think my life can develop into a better life. Thank you. I look forward to your continued support. 메이저토토

totoright — December 6, 2022

I did so many searches on this subject. As a result, this article is one of the top three articles I want to recommend to people. I know how accurate this article is because I have worked in this field for years. If you are curious about the contents, please feel free to visit my blog. 메이저토토