Talking Points Memo posted an article about a study recently released by the Program on International Policy Attitudes at the University of Maryland. The study looks at misinformation about issues related to the 2010 election among the U.S. electorate. The survey sampled 616 individuals who reported that they voted in the November elections, and according to their methodology, was chosen to be representative of the overall U.S. population. After individuals were chosen to take part, they were asked to complete an online survey; those who didn’t have access to a computer were provided with a laptop and internet access. You can read more about this method of collecting data, which uses an online program called Knowledge Networks, here.

Of course, any study of misinformation brings up the tricky question of how to identify what is “true,” and how to do so in a way that isn’t itself political. The authors explain at length:

…we used as reference points the conclusions of key government agencies that are run by professional experts and have a strong reputation for being immune to partisan influences. These include the Congressional Budget Office, the Department of Commerce, and the National Academy of Sciences. We also noted efforts to survey elite opinion, such as the regular survey of economists conducted by the Wall Street Journal; however, we only used this as supporting evidence for what constitutes expert opinion. In most cases we inquired about respondents’ views of expert opinion, as well as the respondents’ own views…in designing this study we took the position that some respondents may have had correct information about prevailing expert opinion but nonetheless came to a contrary conclusion, and thus should not be regarded as ‘misinformed.’

…

On some issues, such as climate change, there is a vocal dissenting minority among experts. Thus questions were framed in terms of whether, among experts, more had one or another view, or views were evenly divided.

The researchers first asked if respondents believed they had seen or heard misleading or incorrect information during the fall campaign. Overall, a majority of voters said they had encountered misinformation during the election, and over half said there was more misinformation this time than usual.

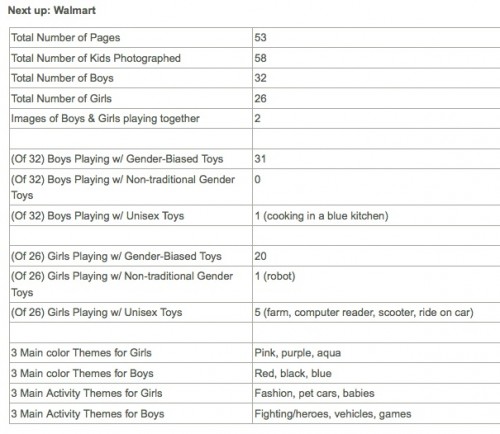

The results also indicated relatively high levels of misinformation on a number of questions. For instance, 40% thought the Trouble Assets Relief Program (TARP, or the bank bailout) was passed under President Obama, when it was actually passed under President Bush; 43% didn’t know that President Obama has increased the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan. And overall, respondents seemed quite confused about financial policies, with overwhelming majorities of both Republicans and Democrats getting questions about taxes, the stimulus, and the auto maker bailout wrong:

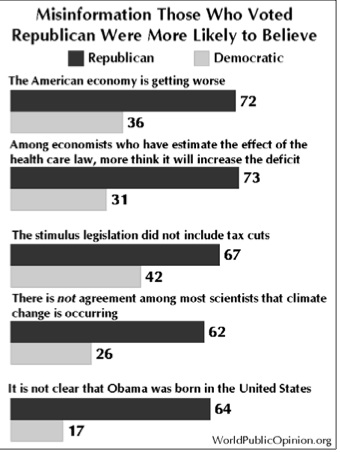

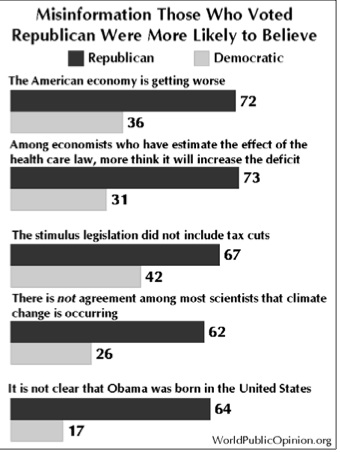

However, for most items, Democrats and Republicans tended to differ on which issues they were misinformed about, in fairly predictable ways:

Finally, the study found that source of information seemed to play a role. Those who said they watched Fox News were more misinformed than any other group, and the more they watched it, the more misinformed they were — whereas with most other news sources, the more news individuals consumed, the less misinformed they were. Viewers of Fox News were more likely to believe the following (incorrect) statements (from p. 20 of the report):

- most economists estimate the stimulus caused job losses (12 points more likely)

- most economists have estimated the health care law will worsen the deficit (31 points)

- the economy is getting worse (26 points)

- most scientists do not agree that climate change is occurring (30 points)

- the stimulus legislation did not include any tax cuts (14 points)

- their own income taxes have gone up (14 points)

- the auto bailout only occurred under Obama (13 points)

- when TARP came up for a vote most Republicans opposed it (12 points)

- it is not clear that Obama was born in the United States (31 points)

This pattern persisted regardless of political affiliation — Democrats who reported watching more Fox News were more misinformed than other Democrats, though less so than Republicans who watch the same amount of Fox News.

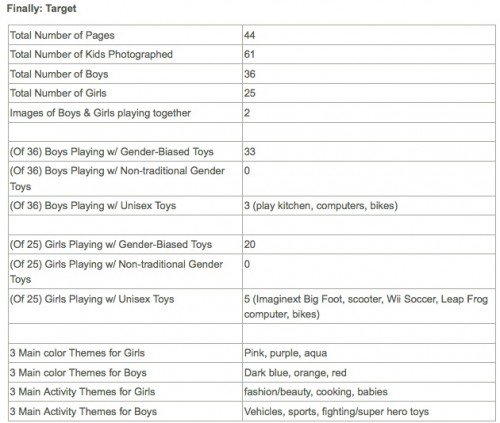

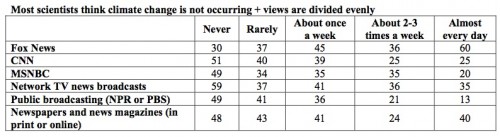

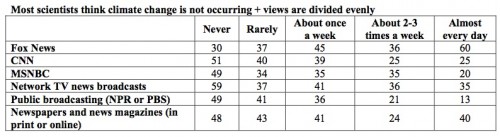

This table shows the number of respondents who said most experts believe climate change either isn’t occurring or that the scientific community is evenly split, by source of news and how often they view that source (p. 21):

They have the same breakdown of data for each question. In general, the lowest levels of misinformation were found among those who reported high levels of consumption of news from MSNBC and/or PBS/NPR. However, as the study authors point out, for a number of questions (such as those about the effects of the stimulus program), all groups had quite high levels of misinformation.

Of course, this leaves a number of questions unanswered: are people more misinformed because they watch Fox News? Or are misinformed people more likely to watch Fox News at least in part because it is more likely to reinforce ideas they already have?

And how does the choice of these particular questions, out of all the potential questions we could ask to judge how well- or poorly-informed people are, affect the results? I suspect critics might say that many of these questions are ones liberals are more likely to get right simply by answering based on political ideology, regardless of actual knowledge — for instance, someone who is Democratic might be more likely to say the health care bill wouldn’t add to the deficit, and thus be “right,” but answer that way because health care reform was a Democratic-backed policy and thus something they supported, not because they have any concrete knowledge about it. As we see with the question about the Chamber of Commerce, when a question doesn’t fit so well with liberal-leaning views (the Chamber of Commerce tends to be more popular among conservatives), Democrats showed high levels of misinformation as well. If we asked more of those sorts of questions, would we find that Democrats (or, say, those who report PBS or NPR as their main source of information) were more misinformed than Fox viewers?

Thoughts?