Flashback Friday.

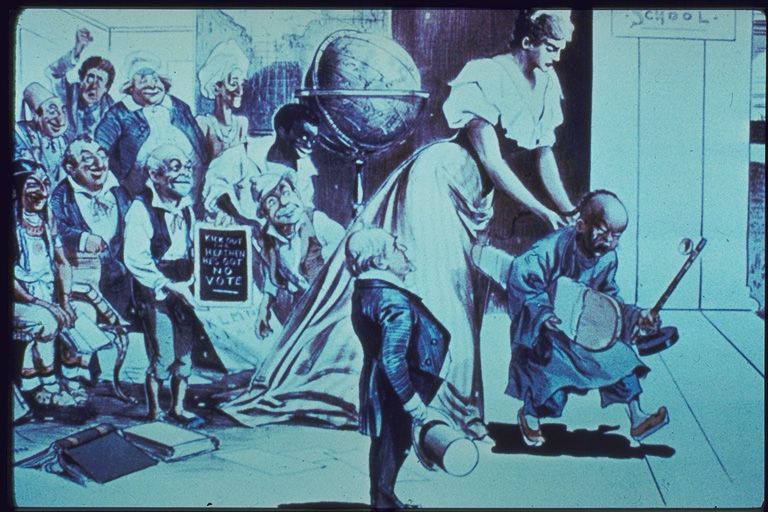

When I was in grad school studying sociology of agriculture, one thing we talked about was organic agriculture and the difference between “organic” and “sustainable.” Most consumers think of these words interchangeably. So, when many people think of an organic dairy farm they imagine something along the lines of these images, the top results for an image search of “organic dairy farm”:

So happy! So content! And, we assume, raised on a small family farm in a way that is humane and environmentally responsible. Those, are, after all, two of the things we expect when something is defined as “sustainable”: it is environmentally benign and humane. We also usually assume that workers would be treated decently as well.

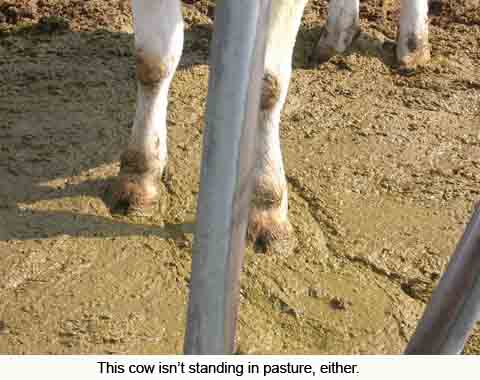

But there is no reason that those elements considered essential to sustainability have to have much to do with organic agriculture. Depending on who is doing the defining, being “organic” can involve very little difference from conventional agriculture. Having an organic dairy mostly just requires that the cows not have antibiotics or homones used on them, eat organic feed, and have access to grass a certain number of days per year. In and of itself, organic certifications don’t guarantee long-term environmental sustainability or overall humane treatment of livestock.

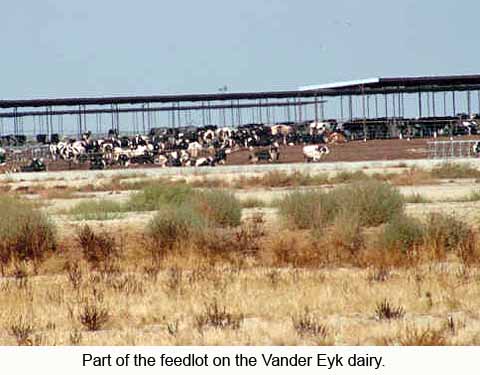

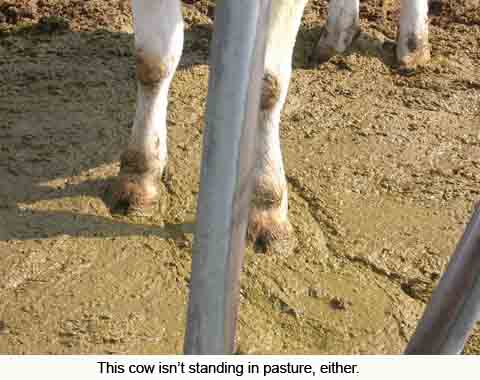

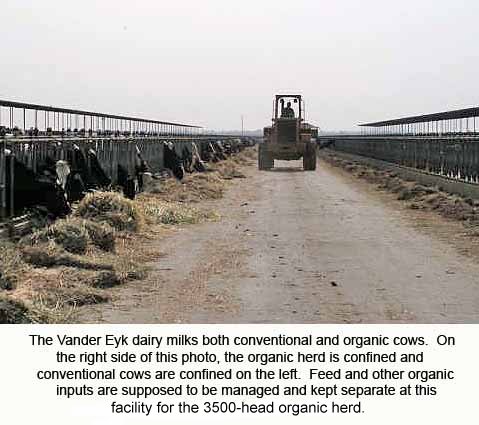

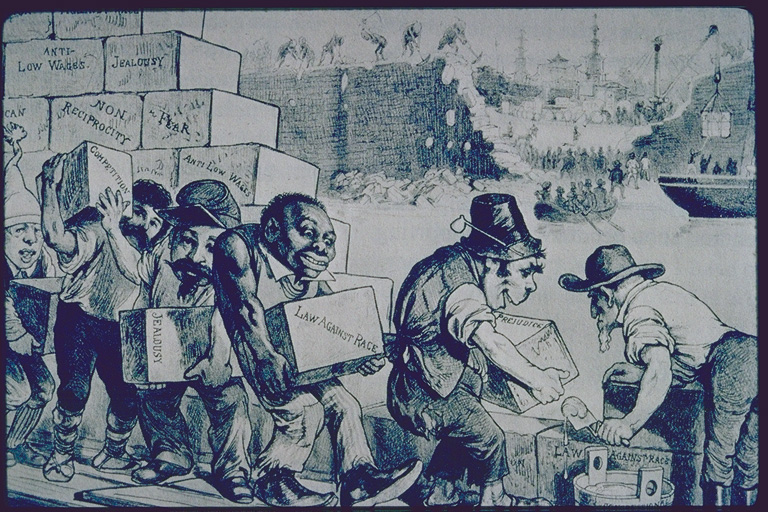

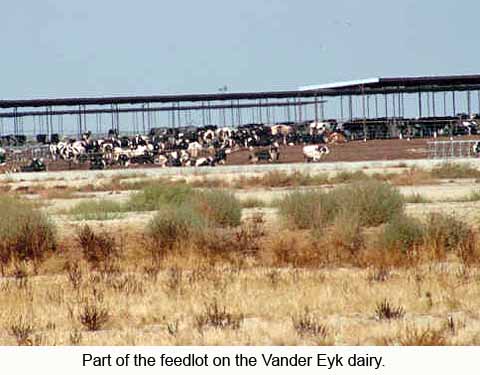

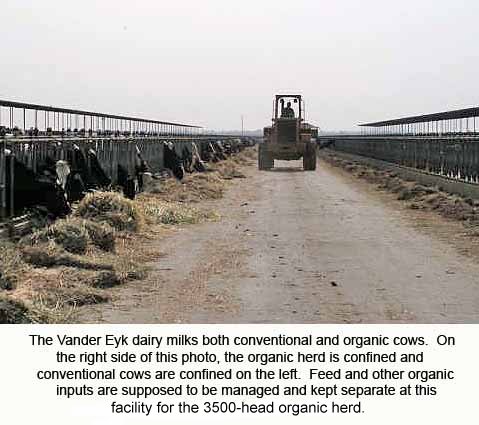

A great illustration of how little the modes of production on organic farms may differ from conventional agriculture is the Vander Eyk dairy. It is an operation in California with over 10,000 dairy cows. Here are some images (found here and here):

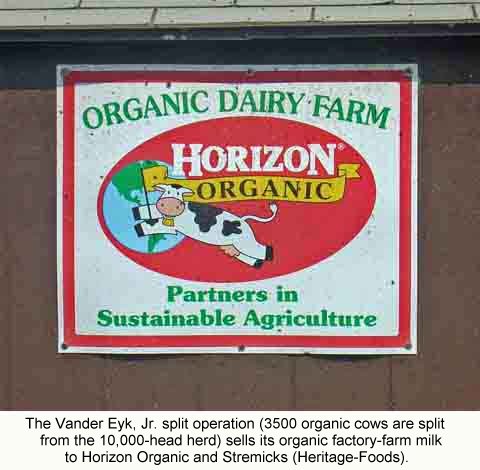

As the caption to the last image makes clear, the Vander Eyk dairy had two herds on the same property, but segregated from one another: the majority of the herd produced conventional milk, while 3,500 cows produced organic milk for sale under the Horizon brand:

In 2007 the Vander Eyk dairy lost its organic certification for violating the requirement that organic dairy cows spend a certain amount of time on pasture. They had cows on pasture, but they were non-milking heifers, not cows that were being milked at the time. What we see here is that the label “organic” doesn’t guarantee most of the things we associate with the idea of organic or sustainable agriculture (and in cases like Vander Eyk, may not even guarantee the things the label is supposed to cover).

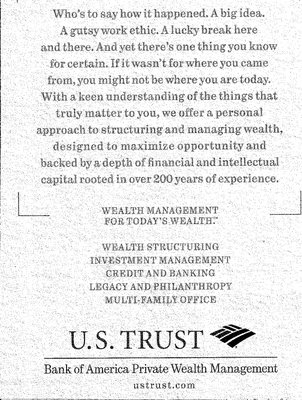

This isn’t just in the dairy industry. As Julie Guthman explains in her book Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California, many types of organic agriculture include things you might not expect. For instance, organic producers in California joined with other producers to oppose making the short-handled hoe illegal — the bane of agricultural workers everywhere (and most infamously associated with sharecropping in the South in the early 20th century) — because they want workers to do lots of close weeding to make up for not spraying crops with pesticides. So, though we often assume organic farmers would be labor-friendly, in that case they opposed a change that agricultural workers supported.

Many organic crops are grown on farms that are the equivalent of the Vander Eyk dairy; most of the land is in conventional production, but a certain number of acres are used to grow organic versions of the same thing. Often the producer, which may be an individual farmer or a corporation such as Dole, isn’t very committed to organics; if a pest infestation threatens to ruin a crop, they’ll just spray it and then sell it on the conventional market rather than lose it. They may then have to have the land re-certified as “in transition,” meaning it hasn’t been pesticide-free long enough to be declared completely organic, but many consumers don’t pay too much attention to such distinctions.

The Vander Eyk dairy — and lots more examples of large containment-facility operations selling to Horizon and other brands at the Cornucopia Institute’s photo gallery — are interesting examples of how terms like “organic,” “green,” and “eco-friendly” don’t necessarily mean that the item is produced according to any of the standards we often assume they imply.

Originally posted in 2009.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.