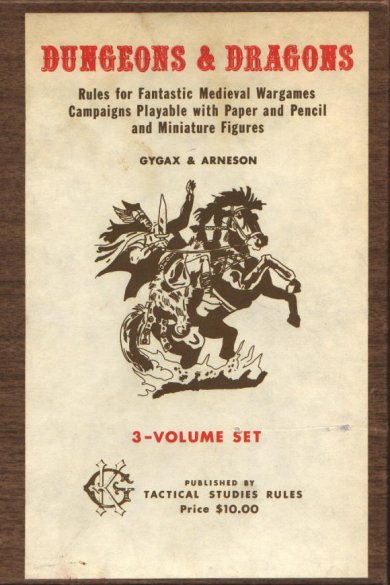

Caspian P. and his roommates sent us a link to the newest Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) Playbook cover. It seems it makes quite a departure from previous editions. (D&D fans: I’m reconstructing this history from here, so let me know if I make any significant mistakes in my summary.)

Various versions of the D&D Playbook–e.g., regular or basic, advanced, and expert– have been published. For the sake of simplicity, I’m going to treat them all equivalently.

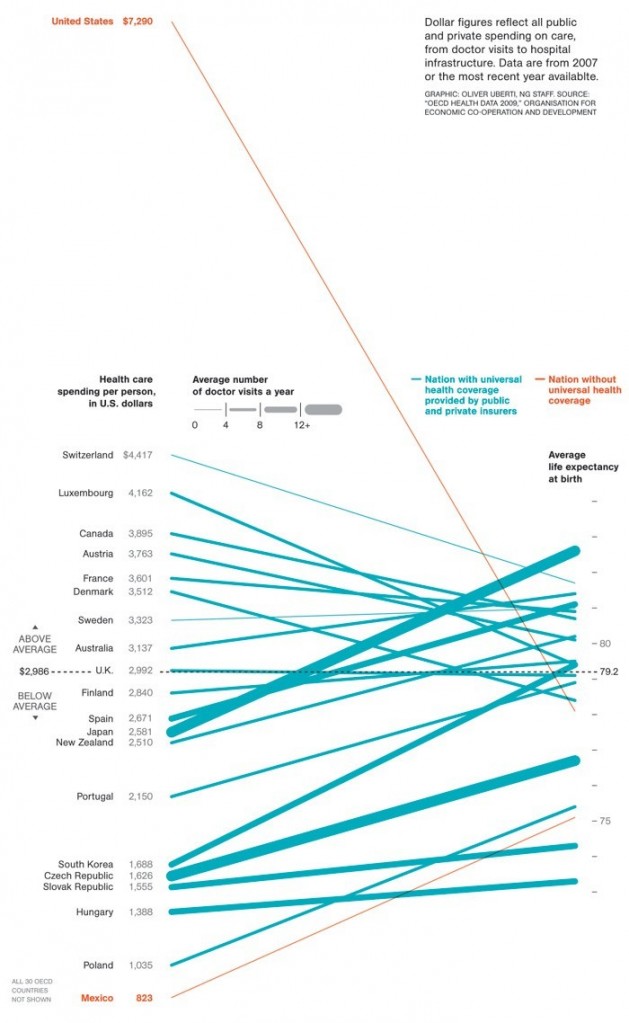

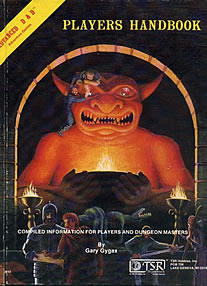

The first D&D Playbook (1971):

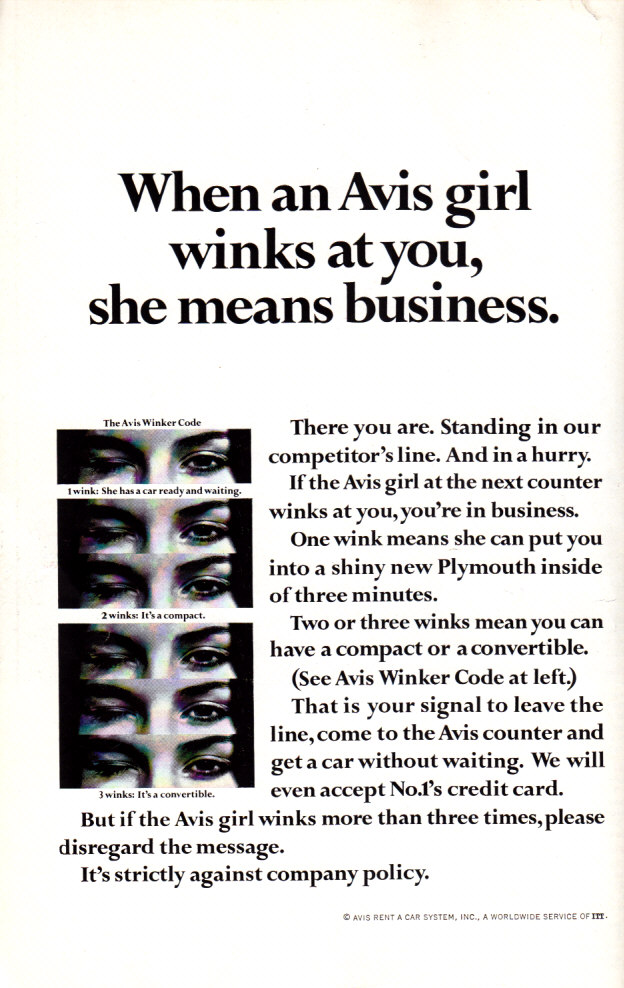

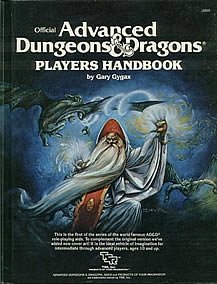

1981:

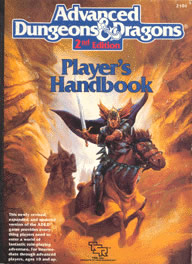

Playbooks from the late 1980s:

You might have noticed that the covers include fantastical creatures and male warriors and wizards… but no women.

In 2000, ownership of the game changed hands and the new cover simply looked like this:

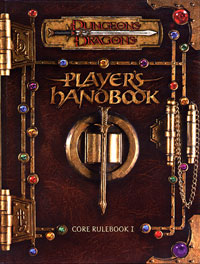

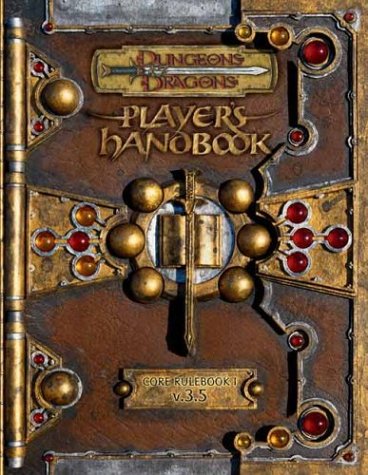

And then this (2003):

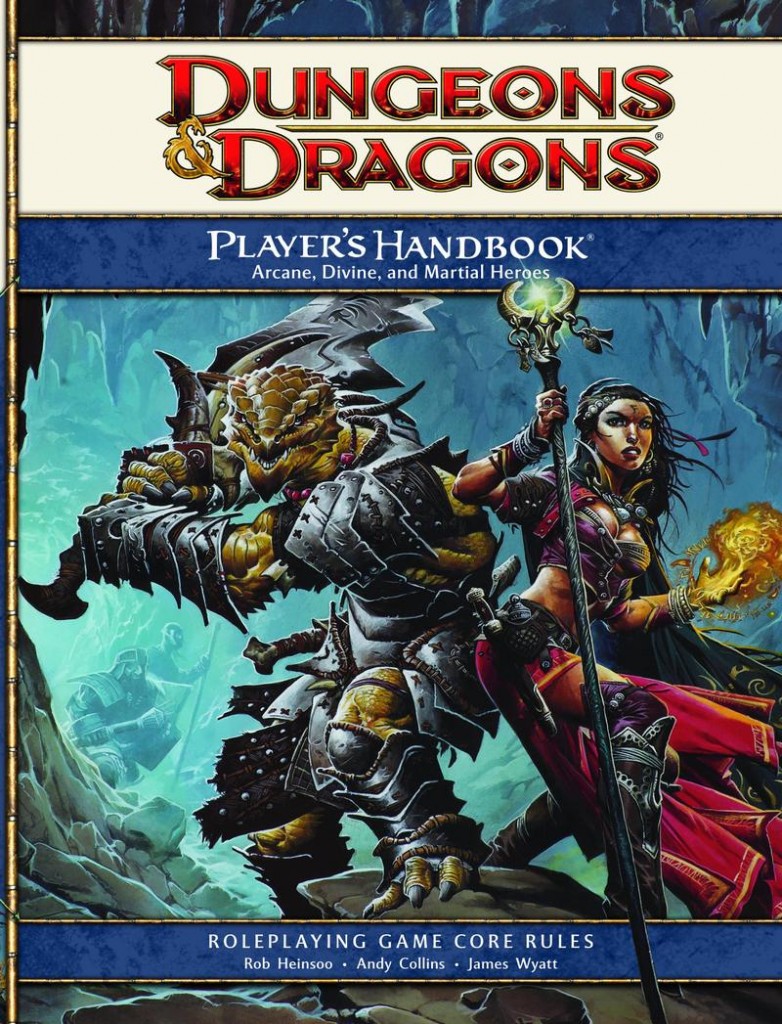

And then the Playbook went the way of the Evony ads:

Caspian wrote that he’s played D&D for years and always felt that it included great female characters. So he was disappointed with the inclusion of a highly sexualized, part-naked woman on the recent cover, prompting him to send it to us.

Consider the new cover alongside our posts on Gossip Girl promotions, the New Beverly Hills 90210, the Burger King shower girl, this crazy post on hot horses and puppies, and the makeovers of Dora the Explorer, Holly Hobbie, Strawberry Shortcake, and the Sun Maid.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.