A few years ago, I bought two orange traffic cones at a hardware store for twenty bucks. It was one of the best, most stress-relieving purchases I made.

Parking space is scarce in big cities. In our car-centered culture, the rare days you absolutely need a large truck in a precise place can be a total nightmare. These cones have gotten me through multiple moves and a plumbing fiasco, and they work like a charm.

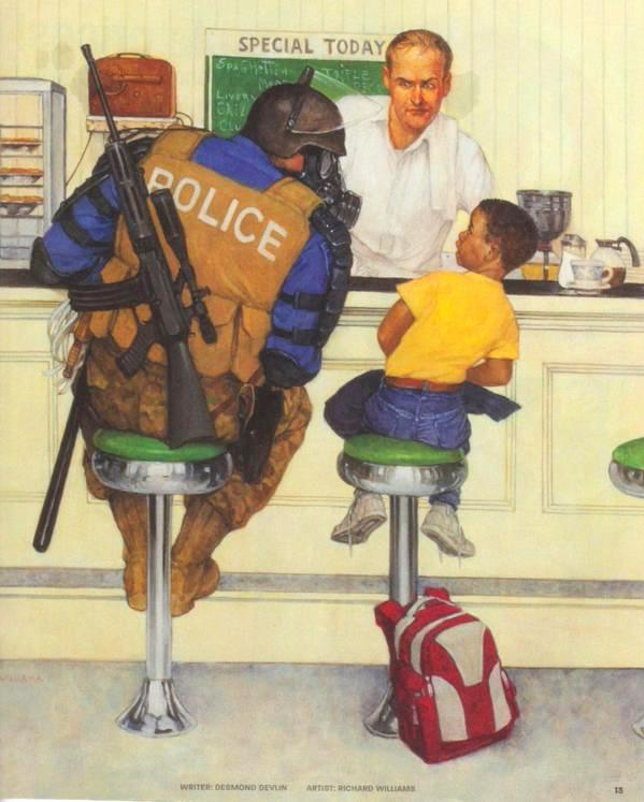

The other day, in the middle of saving space to address said plumbing fiasco, a neighbor walked up to me and politely asked what was going on. They were worried their car was going to get towed. I reassured them that I was the only one having a horrible day, and I started thinking about how much authority two cheap plastic cones had. There was nothing official about them (they even still have the barcode stickers attached!), but people were still worried that they were trespassing.

The point of these cones wasn’t to deceive anyone, just to signal that there is something important going on and that people might want to stay clear for a little while. The same thing happens when a neon vest and an unearned sense of confidence let people go wherever they want.

Saving parking spaces like this is a great case of social theorist Max Weber’s distinction between power and legitimate authority. I can’t make anyone choose not to park where my plumber will need to be. What I can do is use a symbol, like a traffic cone, that indicates this situation is special, there is a problem, and we need space to deal with it. If people accept that and choose not to run over the cones, they have successfully conveyed some authority even if I actually have none. My neighbor accepts some legal authority, because they know people can be ticketed or towed, and they accept some traditional authority, because orange cones and traffic markers have long been a way we mark restricted spaces.

At this point, it is easy to say this is silly or superficial. You would be right! It is totally absurd that anyone would “listen” to the cheap plastic cones, but I think that is exactly the point. When you can’t force people to do things, social signaling like this becomes really important for fostering cooperative relationships. Symbols matter, because they help us confirm that we are willing to cooperate with each other, and they give us the ability to take each other at our word. If only there was a way to use them for something larger, like a global health emergency. From sociologist Zeynep Tufekci:

Telling everyone to wear masks indoors has a sociological effect. Grocery stores and workplaces cannot enforce mask wearing by vaccination status. We do not have vaccine passports in the U.S., and I do not see how we could…In the early days of the pandemic it made sense for everyone to wear a mask, not just the sick…if only to relieve the stigma of illness…Now, as we head toward the endgame, we need to apply the same logic but in reverse: If the unvaccinated still need to wear masks indoors, everyone else needs to do so as well, until prevalence of the virus is more greatly reduced.

Sociological Song of the Day: JD McPherson – “Signs & Signifiers”

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.