Black history in Appalachia is largely hidden. Many people think that slavery was largely absent in central and southern Appalachia due to the poverty of the Scots-Irish who frequently settled in the area, and who were purportedly more “ruggedly independent” and pro-abolitionist in their sentiments. Others argue that the mountainous land was not appropriate for plantations, unlike other parts of the South, and so slavery in the area was improbable.

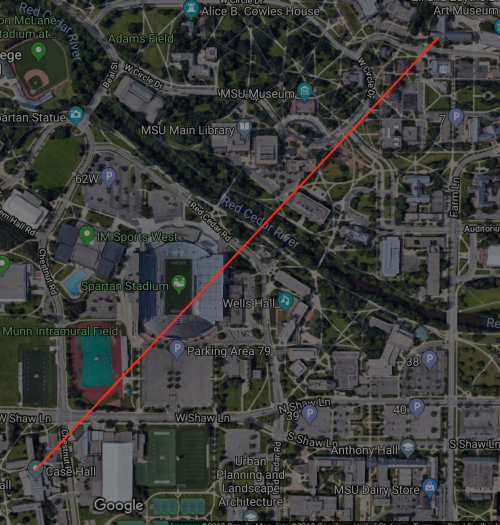

(Wikimedia Commons)

As historian John Inscoe and sociologist Wilma Dunaway show us, this is not the case. According to Inscoe, slavery existed in “every county in Appalachia in 1860.” Dunaway—who collected data from county tax lists, census manuscripts, records from slaveholders, and slave narratives from the area—estimates that 18% of Appalachian households owned slaves, which compares to approximately 29% of Southern families, in general.

While enslaved people in the Appalachian region were less likely to work on large plantations, their experiences were no less harsh. They often tended small farms and livestock, worked in manufacturing and commerce, served tourists, and labored in mining industries. Slave narratives, legal documents, and other records all show that slaves in Appalachia were treated harshly and punitively, despite claims that slavery was more “genteel” in the area than the deep South.

My own research, which focuses on the life experiences of Leslie [“Les”] Whittington, whose grandfather was enslaved, helps to document the presence of slavery in Appalachia and the consequences that exploitative system had for African Americans in the region. Les’s grandfather, John Myra, was owned by Joseph Stepp, who lived in Western North Carolina. Census records show that Joseph Stepp owned seven slaves in 1850, five women and two men, who together ranged from one to 32 years of age. Ten years later, in 1860, schedules show Stepp owned 21 slaves, making him one of the wealthiest property owners in Buncombe County, the county in which he and John Myra lived.

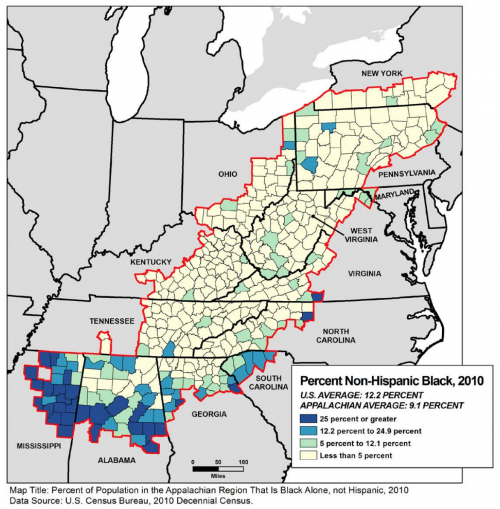

Joseph Stepp was not unique. According to Dunaway, slave owners in Appalachia “monopolized a much higher proportion of their communities’ land and wealth” compared to those outside the area, driving wealth inequality in the region. Part of the legacy of slavery, these inequities remained in place after the Civil War, reinforced by Jim Crow legislation that subjugated African Americans socially, culturally, and politically. Sociologist Karida Brown explains how Jim Crow Laws led approximately six million African Americans to migrate from the South to the North between 1910 and 1970.

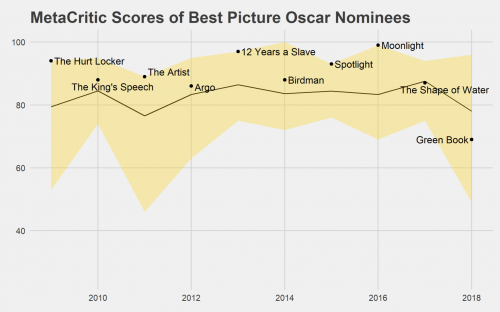

Click to view report

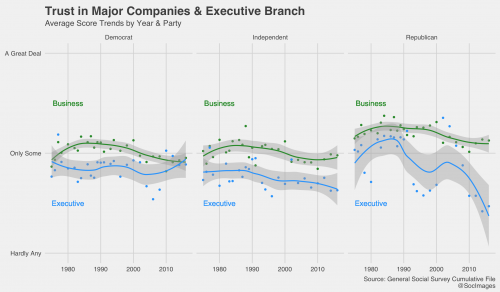

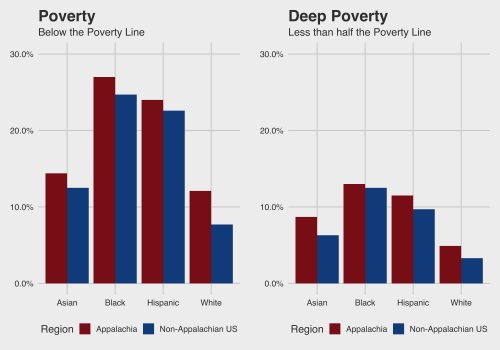

Graphic by Evan Stewart

Those who stayed in Appalachia, such as John Myra and his descendants, faced continued restrictions, like living in racially segregated neighborhoods, having limited employment opportunities, and not being able to attend racially integrated schools. Such systematic forms of discrimination explain why racial disparities continue to exist today, even within a region where poverty among whites remains above the national average. To understand these existing inequities, we must document the past accurately.

Jacqueline Clark, PhD is a professor of sociology at Ripon College. Her teaching and research interests include social inequalities, the sociology of health and illness, and the sociology of jobs and work.