Dmitriy T.M. sent us a report from the Nielsen company of time spent watching TV and using the internet.

We do, of course, want to take into account possible sample bias–the data are based on answers from Nielsen TV and internet panel participants and a survey of cell phone users, and there’s likely some self-selection bias there, with some groups being more likely to participate than others. I know I’ve read about concerns with Nielsen’s data within the entertainment industry.

That said, while I would be cautious about reporting the data as representative of the U.S. overall, the general trends are interesting. People 65+ watched over 47 hours of traditional (non-recorded) TV per week? Can that be possible? The only 65+-year-old whose TV-watching habits I know is my grandma, and she does tend to have the TV on at all times, even when she’s in the kitchen and is just listening, not watching.

According to these data, among those of retirement age, TV watching is basically more than a full-time job. Kids aged 2-11, on the other hand, only have a part-time job watching TV, at about 25 hours per week.

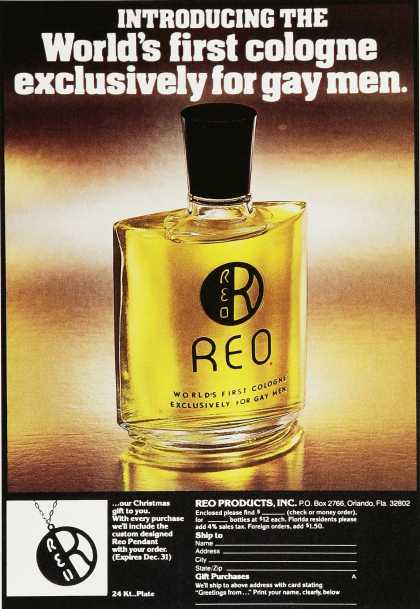

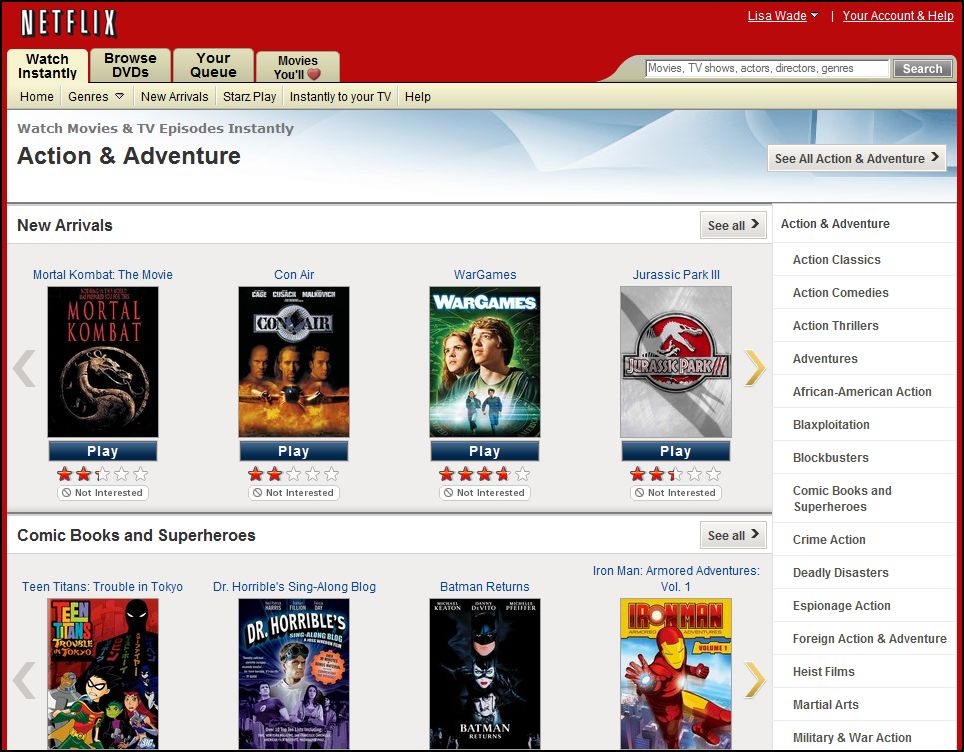

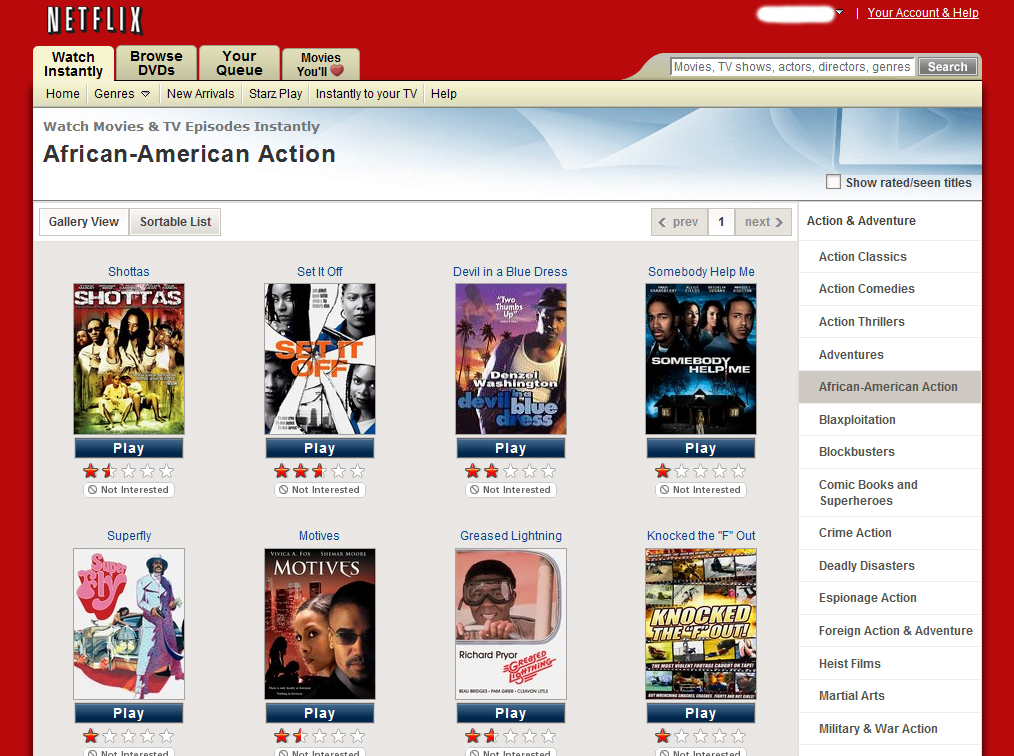

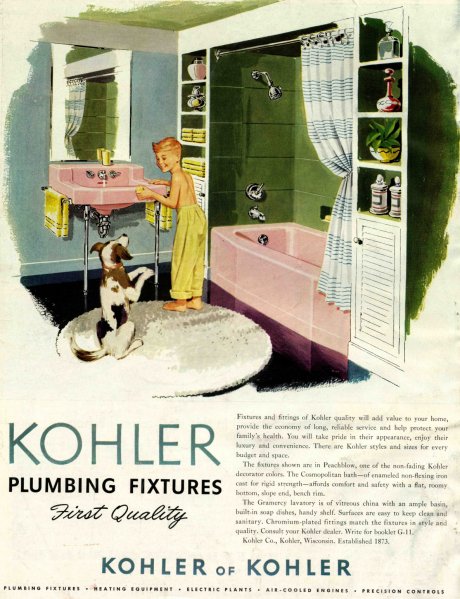

I, of course, had to sit down and calculate my own TV watching, which came out at a little over 6 hours per week when my friends and I have our Friday night TV watching get-together, 3 hours when we don’t. Less than I thought, overall. I am, however, that advertising nightmare, the person who watches 100% of TV online or DVRd, thus reducing the number of commercials I’m exposed to. You can blame me and others like me for the increasing number of product placements you see in TV shows, a way to try to incorporate sponsorship directly into the content rather than in separate commercials that people are finding more ways to skip.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.