Nothing better captures my modus operandi than this quote from Yogi Bhajan. For 50 years as an organizer and teacher, I have used this strategy to confound individuals and groups, prodding them into a pursuit of personal and collective liberation. Too often, this pragmatic method comes with a dogmatic, “other-worldly” metaphysic; it need not. It is just a “this-worldly” practice of adult education, unencumbered by any ideology.

I first left my hometown at age 16 as a pariah, the cautionary tale of juvenile delinquency. A nurturing aunt and uncle had persuaded my parents to let them take me in and try to detour my path to perdition. It only accelerated the pace.

On Fridays, I would hitchhike back home. Rides were unpredictable and once a driver dropped me off at a country crossroads, inhabited only by a ramshackle gas station with a makeshift bar. After waiting an hour for a ride, I wandered in and ordered a beer. I was the sole customer and the owner seemed unconcerned about underage drinking. After three or four beers, he got a call. He said he had to run an errand and asked if I would watch the place.

Opening another beer, I begin pondering my wretched life. It was just one of a lifetime of rash decisions. I filled my suitcase with beer and climbed into the cab of the station’s gas truck. Unfortunately, the keys were in the ignition. The crossroads offered four options. Mephistopheles had never spoken to me so directly: “Go West young man and seek fame and fortune.”

I had been barreling along at 75 mph for about 30-35 miles when the flashing red lights of three squad cars first appeared in the rear view mirror. I figured they were still two to three miles behind me but closing fast. I had to beat them to the next hamlet about three miles ahead. I cranked the engine to its limit of 95 mph and roared into the little town full throttle.

I pulled behind some grain elevators and jumped from the still moving vehicle —with my suitcase of beer intact. I ran to a grain silo, climbed 50 feet of outside ladders, and dropped into a sea of corn kernels, buried up my neck. I guzzled beer until a highway cop leaned into the opening and spotted me with his flashlight. Treatment for alcoholism was still 16 long years away.

For town fathers, enough was enough

They transported me to the Jackson County jail. The next morning they marched me across the street to the courthouse. The town fathers had decided enough was enough.

I ended up graduating high school at the Red Wing “Boys Reformatory,” forever banished from the records of the Jackson High School class of 1963.

With shame and defiance, I voluntarily emigrated from the soil of my ancestors and its offspring. I remember well fleeing in a battered, gray 1949 Plymouth. I immigrated to a foreign land, eventually transplanting myself into a more cosmopolitan landscape.

Nevertheless, my hometown remained the psychic map from which I sought to distance myself from the provincial culture and values of my youthful years from 1945 to 1961. I could never listen to the songs on Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” without imagining that bend in the Des Moines River. In other words, you can take the boy out of Jackson County, but you can’t take Jackson County out of the boy.

Reconciliation

In 2010, a terminal cancer had invaded both my body and identity. Suddenly my story of dying went viral, appearing statewide and beyond in newspapers, on TV, radio, and the Internet. Much to my astonishment, a number of former classmates reached out to me with compassion and affection. They had extended an invitation of reconciliation. Hesitantly, I reciprocated.

As a result, when an invitation arrived for their 50th class reunion, I decided to return for the first time as an honorary graduate. I drove southwest for 180 miles with considerable trepidation. Arriving at the last minute without benefit of a nametag, few recognized me. Of the 107 class members, 22 candles flickered for those who had passed, 53 of the remaining 85 attended — a remarkable percentage. Of the 53, 13 of us had become teachers. Perhaps there was something more than fluoride in that landmark water tower.

After two restorative days, I drove home for three hours, luxuriating in my classmates’ welcoming balm that heals the soul. Only then did I fully understand what a festering emotional wound my 50-year estrangement had been.

It was a godsend for this prodigal son to see up close and personal how each of us have been participants in the same human comedy, sharing a plethora of trials and tribulations, triumphs and tragedies. Along this haphazard pilgrimage, all we really have is each other. To the remaining members of the class of 1963, a heartfelt thank you for sharing the early morning and late evening of my brief, but eventful, sojourn on this earth.

Don’t be a stranger.

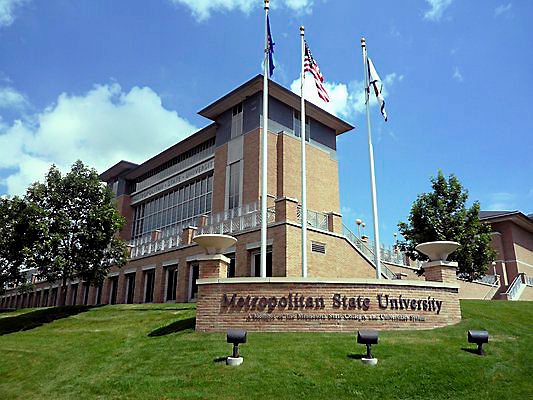

Monte Bute teaches sociology and social science at Metropolitan State University.