Collectively, Americans have a particular idea of what constitutes genocide. Notions of the Holocaust, Cambodia, or Rwanda are generally what come to mind. Almost universally they have two things in common; they are tied to events that happen abroad, and they involve killing on a massive scale. This clear notion of what constitutes genocide can be traced back to the legal definition of genocide, found in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

This legal framework for genocide itself can be traced back to 1944, in the midst of World War II, when the horrors of the Holocaust were being increasingly brought to the forefront. Jurist Raphael Lemkin published a series of guidelines that would allow for the prosecution of the heinous Nazi crimes.

In Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws Of Occupation, Analysis Of Government, Proposals For Redress Lemkin culminated his years of work defining and redefining what he considered the crime of crimes. The legal language found in the Genocide Convention, however, differs greatly from that in Axis Rule. Fortunately, many scholars have carried the torch of Lemkin forward, continuing to examine how we define genocide.

From this scholarly work, we can find a more nuanced and expanded approach to genocide that has allowed us to examine the events of the past with a more critical lens. Events like the treatment of Native youth in America’s boarding school system throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries have become widely accepted instances of genocide. Moreover, the policies and attitudes towards Native people have dramatically shifted over the years to the point that in 2012 the city councils of both Minneapolis and St. Paul condemned the treatment of the Dakota following the 1862 war as genocide.

These public declarations fall well short of a legal threshold, though. When the time came in 1948 to establish the crime of genocide as codified law much of the basis for defining genocide that Lemkin established in Axis Rule was diluted. Instead of a legal framework that recognized crimes like political, social, or cultural genocide, the newly established United Nations limited the scope of genocide almost entirely to physical genocide, the targeted killing and elimination of a group.

The Soviet Union is usually charged with watering down the language found in the UN Genocide Convention, but in his book Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes scholar, William Schabas, points out that many of the Soviet’s concerns were equally shared by the American delegation. There was a desire to avoid future prosecution of acts committed by the American government that would clearly meet the threshold under Lemkin’s expanded definition of genocide, especially as it related to policies towards Native and Black groups in the United States.

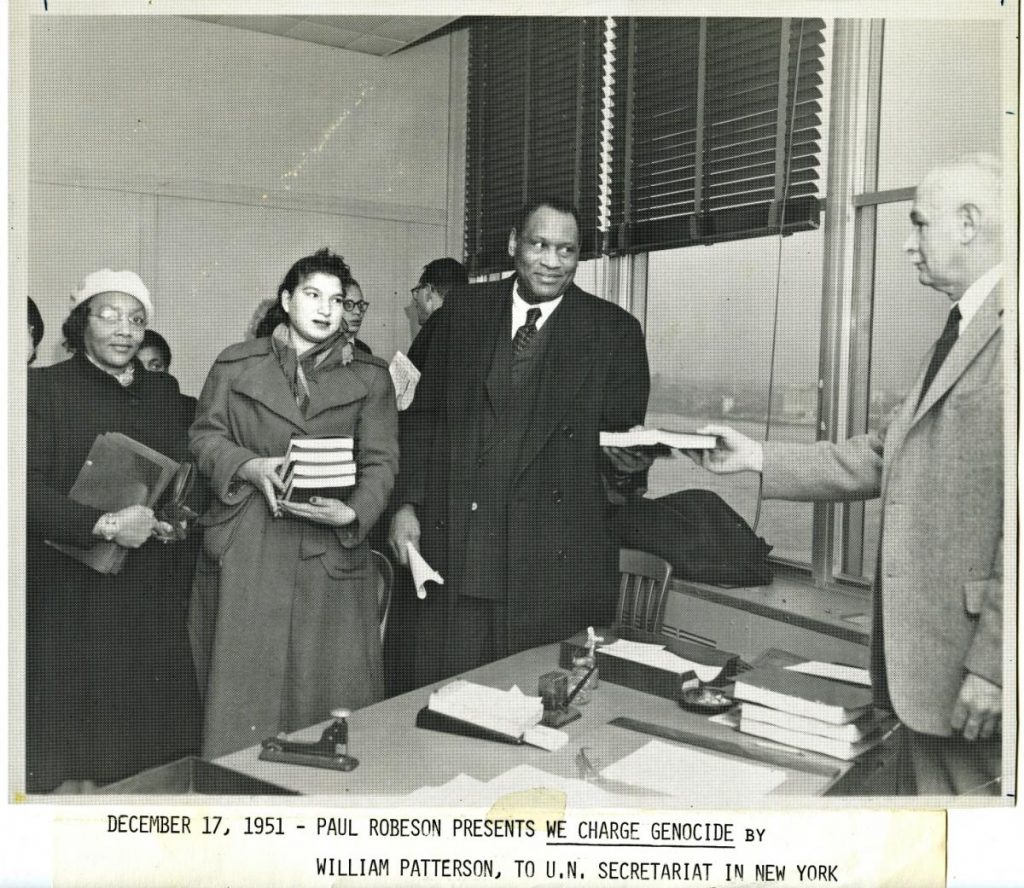

As the United Nations was coming into its own in 1945, the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was mobilizing itself and its constituents to bring forth injustices against the Black community. Policies like poll taxes, literacy exams (to that end, Jim Crow laws as a whole that disenfranchised Black America while establishing and preserving segregation), along with systemic violence and economic policies meant to dehumanize Black Americans were laid out in a petition to the UN that made the case for genocide. The movement was called We Charge Genocide.

The movement culminated in a petition delivered to the UN General Assembly in 1951. It reads as though it could have come from today’s headlines :

On Killing Members of a Group:

Our evidence concerns the thousands of Negroes who over the years have been beaten to death on chain gangs and in the back rooms of sheriff’s offices, in the cells of county jails, in precinct police stations and on city streets, who have been framed and murdered by sham legal forms and by a legal bureaucracy.

In regards to Economic Genocide:

We shall prove that the object of this genocide, as of all genocide, is the perpetuation of economic and political power by the few through the destruction of political protest by the many. Its method is to demoralize and divide an entire nation; its end is to increase the profits and unchallenged control by a reactionary clique.

Particularly harrowing is a passage discussing the evidence the CRC intended to bring forward, which feels especially pertinent to today’s climate:

Once the classic method of lynching was the rope. Now it is the policeman’s bullet. To many an American the police are the government, certainly its most visible representative. We submit that the evidence suggests that the killing of Negroes has become police policy in the United States and that police policy is the most practical expression of government policy.

The petition goes on to call on the UN to examine the case — to complete the investigation of genocide, but it never came. Almost immediately, We Charge Genocide was disregarded by the American delegation. Eleanor Roosevelt, former First Lady of the United States and the first US delegate to the UN Commission on Human Rights wrote of the petition “It will do great harm at home because the answers to untruths and half-truths are always less dramatic than the assertions,” identifying the authors as communist instigators rather than the victims of systemic violence and racism.

Ultimately, and not surprisingly, the petition went nowhere. The United States, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council with its veto power, clearly had enough influence to ensure the petition would never receive an acknowledgement from the UN.

We Charge Genocide has served as a catalyst for further recognition of Black genocide. The banner has now been taken up by other groups who have used the spirit of the 1951 petition to call attention to contemporary issues impacting Black communities: policies of forced sterilization throughout the 20th century, challenges to the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the disproportionate rates of incarceration amongst people of color.

We Charge Genocide has re-emerged through the work of a non-profit group in Chicago. Advocating for marginalized communities impacted by policy violence, We Charge Genocide connects the current calls for law enforcement accountability in America’s third-largest city, naming the very injustices laid out in 1951.

The question of genocide has largely been ignored in the nearly seven decades since We Charge Genocide began. The movement itself received little coverage in the media, and it has been largely forgotten. This raises challenging questions: Why are Americans open to acknowledging one genocide but ignore another? As our understanding and willingness to comprehend episodes of our painful past continue to expand, will there come a point in which the conditions listed in the We Charge Genocide’s petition are accepted for what they are — genocide?

Recent polls have indicated eroding support for Black Lives Matters and similar campaigns calling for racial justice protests, so the potential for Americans reckoning with another aspect from our genocidal past seems unlikely, for now.

Joe Eggers is the research and outreach coordinator for the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota.

Comments