Situated adjacent the National Mall in Washington D.C., the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) dominates the landscape of American Holocaust consciousness, remembrance, and education. On an elevator ride to the sixth floor and the start of the permanent exhibit, visitors to the museum watch a 15-second-long video showing footage of American soldiers encountering one of the concentration camps in 1945. In a retrospective voiceover, one soldier reflects on his initial shock at seeing the horrors of the camp: “We had come across something and were not sure what it was – a big prison of some kind. There were people running all over: sick, dying, starved people. You can’t imagine it; things like that don’t happen.” This video foreshadows the incomprehensibility of the Holocaust that visitors are about to witness in the permanent exhibit. The video also serves to perpetuate an American Holocaust myth; the myth that Americans had little to no knowledge of the Holocaust until the reporting of the liberation of the camps in 1945. For, as the myth goes, had Americans known about the atrocities, surely, they would have done something to speak out, to collectively, publicly condemn the mass murder of European Jewry. Though it is entirely possible that this individual soldier may not have known about the Nazi camps, the opening of Dachau in 1933, the persecution and plight of Germany and Europe’s Jews, and the ultimate extermination of millions were widely reported in the New York Times and local papers across the country. A recently-opened exhibit at the USHMM, Americans and the Holocaust, seeks to examine what ordinary Americans knew about the Holocaust in the 1930s and 40s.

History Unfolded

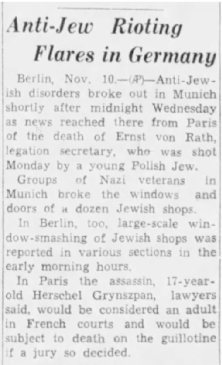

In 2016, the USHMM launched its History Unfolded project, in an attempt to “uncover what ordinary people around the country could have known about the Holocaust from reading their local newspapers in the years 1933–1945.” The project engages high school and college students in identifying and cataloging articles from local and regional newspapers related to one of 37- events from the 1930s and 40s for a growing public archive maintained by the museum. While most events highlight Nazi persecution of Jews, others focus on America’s responses to the growing refugee crisis after 1938, as well as racial segregation, isolationism, and antisemitism within the United States. This archive currently consists of roughly 16,000 articles (including opinion pieces, editorials, letters to the editor, and political cartoons) from every U.S. state; though, few there are very few articles from African American-run newspapers. The pedagogical implications of the archive are twofold: First, the existing archive is fully searchable by city/state, topic, date, or name of the newspaper, allowing teachers and students to search and print individual articles to supplement lessons and projects. Second, the archiving project will enable students to conduct original research online, a local library or historical institution to submit additional articles. Thus, History Unfolded provides an opportunity for students to participate in research and the creation of an active, public archive, both engendering authentic disciplinary skills, as well as engaging in the recasting of a collective narrative around what ordinary American knew about the Holocaust.

Americans and the Holocaust

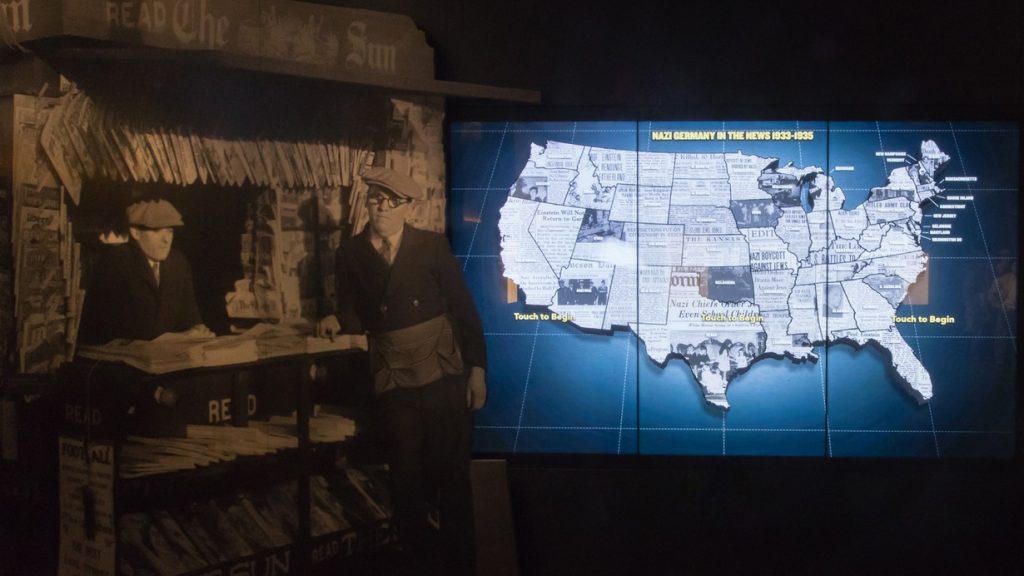

The USHMM’s Americans and the Holocaust exhibit opened in 2018. Visitors to the exhibit are asked to reflect upon two questions: (a) “What did Americans know?” and (b) “What more could have been done?” These questions are repeated throughout the exhibit as visitors examine various events (many mirroring the 37 events used in the History Unfolded archive) related to the persecution of European Jewry, the Holocaust, as well as issues of racism, and antisemitism in Europe and the United States. One of the first displays visitors encounter is a large touchscreen map of the United States, allowing users to search for newspaper articles from the History Unfolded archive. Newspapers from the archive are also used throughout the exhibit to illustrate what the American public could have known about the Holocaust.

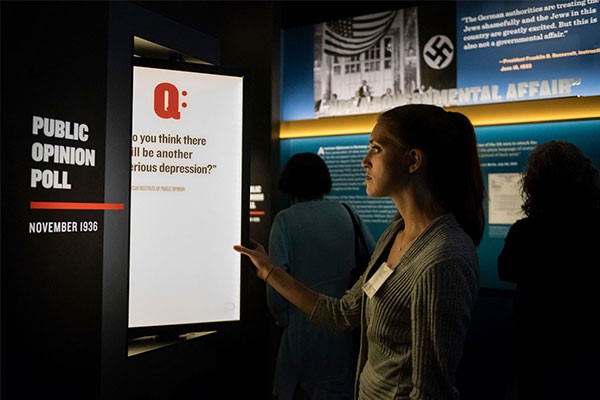

In addition to newspaper and other media coverage of the Holocaust, the exhibit also uses public polling data, displayed on movable pedestals. Visitors first see the poll question, with the responses revealed by spinning the screen.

Reviews of the exhibit have been overwhelmingly positive; though, some scholars have voiced critiques over the omission of particular narratives, such as American corporations and universities’ collaboration with their German counterparts and the Nazi government. Further critiques have focused on the exhibit’s conclusion that the Roosevelt administration’s inaction around easing immigration restrictions or rescuing European Jews was largely the result of their inability to subvert public opinions, which were markedly isolationist. Such critiques trouble the supposed role of public opinion polling, a relatively new development in the 1930s, in influencing government policies and actions.

Teaching with the History Unfolded project and the Americans and the Holocaust exhibit helps to engage students in challenging an American Holocaust myth. Both seem intended to push students to consider their role, as well as that of the larger society, in addressing genocide. Indeed, each year, my students, despite having taken previous courses in American history, are shocked to learn that ordinary Americans had access to reliable, detailed information about the increasing persecution of Europe’s Jews. Inevitably they ask: If they knew about the Holocaust, why didn’t people do something to speak out about what was happening? For these students, History Unfolded and Americans and the Holocaust seem to make it clear that ordinary Americans shirked their moral responsibility to speak out against Nazism and aid Europe’s Jews. Rather than allow students to come away with a simplistic narrative of America’s moral failure during the 1930s and 40s and their assured commitment to “never again,” I push them to consider that the project and the exhibit only suggest what ordinary Americans could have known, not what they did know. Additionally, I ask, are we only able to draw such clear lessons from these events in hindsight, after they have been selectively culled from the millions of other pages of news articles that appeared in the 1930s and 1940s?

In recent years, my students and I have also discussed the ongoing genocide of Rohingya in Burma, of which students have little prior knowledge. We examine contemporary newspaper coverage of the atrocities, which though rarely appearing on the front-page and often absent from algorithm-controlled social media newsfeeds, are, nevertheless, easily accessible for these well-educated and highly-resourced students. Not lacking in opinions about the moral responsibility of the United States to influence the course of the genocide, these students often feel powerless to bridge the knowledge-to-action gap that, in this case, feels more like a chasm. It is at this point in our discussions that we use the History Unfolded project and the Americans and the Holocaust exhibit to examine the role of an unrestricted news media within the public sphere and discuss their roles and responsibilities in advancing civil discourse within democratic civil society.

George Dalbo is the Educational Outreach Coordinator for the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies and a Ph.D. student in Social Studies Education at the University of Minnesota with research interests in Holocaust, genocide, and human rights education. Previously, he was a middle and high school social studies teacher, having taught every grade from 5th-12th in public, charter, and independent schools in Minnesota, as well as two years at an international school in Vienna, Austria.

Comments 1

Dan Schipper — July 20, 2020

How much time is devoted to the genocide of Native Americans by the Government?