When I first saw Fritz Hirschberger’s paintings in art storage, I was struck with cognitive dissonance. In the time that I’ve worked for CHGS, I looked at Hirschberger’s paintings and read about the artist quite a bit, but only in print or online in CHGS’ digital collection.

This was my first encounter with a Hirschberger painting in its physicality. Five feet tall, painted in translucent layers of bright oils, there, before me, stretched a saturated orange and purple canvas filled with the a war horseman brandishing deadly weapons. Hirschberger chose the Fifth Horseman precisely because it could not be discerned through physical senses,* yet here in my first encounter seeing this piece in person, it was arresting precisely because of its physical nature.

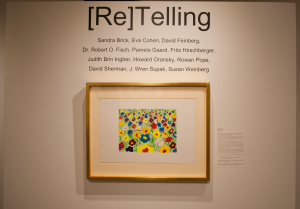

Weeks later, the paintings were installed and ready as part of [Re]Telling, an exhibition of Holocaust art, narrative, and contemporary response, held in the Tychman Shapiro Gallery at the Sabes JCC. Yehudit Shendar, retired Deputy Director and Senior Art Curator of Yad VaShem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial and museum, gave remarks at the opening reception of [Re]Telling featuring seven paintings by survivor Fritz Hirschberger selected from the CHGS permanent collection.

Shendar described Hirschberger as an artist of strong conviction, who painted in response to his experiences and his later historical research into the events of the Holocaust. Hirschberger was a Jew born to Jewish parents in Dresden, whose personal narrative during the Holocaust included forced expulsion, imprisonment in the Soviet Gulag, and military service fighting against the Nazi army. Hirschberger’s personal tragedies and losses led to further historical research, all of which played a role in painting on the subject.

His first Holocaust series is called “Sur-Rational,” precisely because the magnitude of the events of the Holocaust seemed to exist outside of rational explanation. Like many artists responding to the Holocaust, Hirschberger uses religious imagery to further provoke the idea that the Holocaust, a human atrocity, transcends what a human can understand (such as in the “Fifth Horseman,” and “The Same Fire”). This is the cognitive dissonance of Hirschberger’s paintings: they attempt to convey something that evades rational comprehension, and are objects that display the physical crime of the Holocaust. In the corner of the Horseman’s saddle, Hirschberger painted the clearly legible word “Dora,” the name of the labor camp in which his father died.

In the words of Stephen Feinstein, Hirschberger’s work attempts to “bequeath [this] knowledge and visual representation to another generation.” Hirschberger uses concrete historical references to strike an uneasy balance between the incomprehensible magnitude of the Holocaust and the real need to explain, communicate, and teach a historical event. Besides occasional words painted on the canvas, many of his paintings directly reference poetry or other texts that drive lessons and morals home to the viewer (such as “Indifference”). Some of these texts are well-known, but when juxtaposed against the disjointed and naive figures in Hirschberger’s canvases, contribute to a sense of alienation from history.

[Re]Telling showcases this process of handing-down visual representation to another generation by asking local artists and teens to create work in response to his chosen poetry or visuals. In the Tychman Shapiro Gallery, each Hirschberger painting is installed with the works of eleven local artists. Some of the artists made art in response to the literature that Hirschberger himself selected, or were directly inspired by his paintings or their themes and subject matter. In a later post, we will look at these artists’ work in juxtaposition with Hirschberger’s own.

This reflective artistic transmission represented the process of carrying personal narratives forward through generations. No artist replicated Hirschberger’s work, but each valued his testimony through the lens of their own expression. Shendar referred to this reflective process in her remarks, asserting that the past has meaning only when carried forward into the future. At its core, [Re]Telling shows how we give the past meaning, in this case in an artistic process.

In CHGS’ 20th year, this is an appropriate recognition of CHGS’ legacy, and a visible reminder of our mission to further the study of genocide through remembrance, responsibility, and progress.

[Re]Telling was presented by CHGS and the Sabes Jewish Community Center, made possible with support from the Arsham and Charlotte Ohanessian Endowment Fund for Justice and Peace Studies of the Minneapolis Foundation, and the Howard B. & Ruth F. Brin Jewish Arts Endowment, a fund of the Minneapolis Jewish Federation’s Foundation. Please explore these images of the exhibition that continue the life of this art beyond the physical exhibition, and check out CHGS’ entire collection, including past exhibitions.

* Stephen Feinstein further explained Hirschberger’s use of the symbol: “…The four horses are white, red, black, and pale. The name of the Fifth Horseman is said to be Hades or Hell. The Fifth Horseman operates in the shadow of the Fourth. It was common belief, especially during the Reformation, that one could not defend oneself or one’s faith against those things that one was unable to discern with one’s physical senses. The war predicted to be waged by the Fifth Horseman will occur on a different plane. It is a plane that the physical senses are not able to discern.”

Demetrios Vital is Outreach Coordinator for the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. In this role he is responsible for the care and promotion of CHGS art and object collections, as well as working with the community in the development of programs, activities, and events.

The exhibition included a video of Judith Brin Ingber’s choreography for “I Never Saw Another Butterfly” (the poem by Pavel Friedman) performed by Megan McClellan:

Comments