Was Hitler a bully? Evan Selinger, professor of philosophy at the Rochester Institute of Technology, shared in an essay in Slate how his 5-year-old daughter’s teacher compared the “worst criminal in history to a playground tormentor.” Perhaps an extreme example. Yet to understand this increasingly common trend to educate students about “Bully Hitler,” one must recognize two developments that are currently shaping the way teachers, curriculum writers, and educational institutions in the United States are educating young people about the Holocaust. First, there is a universalization of the Holocaust in an attempt to make its study relevant to students’ lived experiences and to provide them with overt moral and ethical lessons in the form of social-emotional and character education. Second, increasingly, many state legislatures have mandated Holocaust education, often suggesting a study in the form of character education to younger students, some as young as elementary school (5-10 years old). New Jersey’s Commission on Holocaust Education, the entity responsible for ensuring schools meet the state’s Holocaust-education mandate, reminds educators that, “the law indicates that issues of bias, prejudice and bigotry, including bullying through the teaching of the Holocaust and genocide, shall be included for all children from K-12th grade.” Thus, increasingly, students are taught to link the Holocaust with bullying and pushed to contemplate the choices they might have made during the Holocaust, as well as the choices they might make in their school’s cafeterias, hallways, and playgrounds as bullies, bystanders, or upstanders.

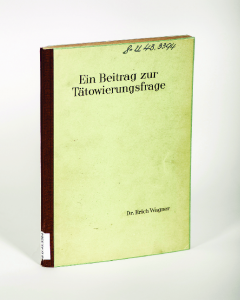

The Spanish daily El País published a shocking story last week about a rare and controversial document from the Buchenwald Nazi Concentration Camp. A PhD Thesis done by a Nazi camp doctor, Erich Wagner, titled On the Subject of Tattoos, that analyzes the tattoos of the camp’s earliest prisoners, many of whom were Jews arrested during Kristallnacht.

The Spanish daily El País published a shocking story last week about a rare and controversial document from the Buchenwald Nazi Concentration Camp. A PhD Thesis done by a Nazi camp doctor, Erich Wagner, titled On the Subject of Tattoos, that analyzes the tattoos of the camp’s earliest prisoners, many of whom were Jews arrested during Kristallnacht.

Wagner “meticulously catalogued the race, nationality, criminal past and education” of those sent to Buchenwald in an attempt to connect tattoos with criminal tendencies – an approach, needless to say, with no scientific merit.

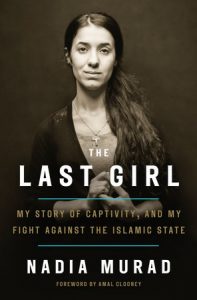

Nadia dreamed of either becoming a history teacher or opening a hair salon in Kocho, Iraq – a small village of farmers and shepherds in southern Sinjar. In her book, The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State (2017), Nadia talks about growing up with her many brothers and sisters amidst a tight-knit Yazidi community. Central to Yazidi identity is the history of the seventy-three past firmans (to mean genocide) committed against the community by outside forces. Nadia, along with others Yazidis, learned about this history but never thought she herself would soon survive a genocide against her own religious community. Nadia writes, “…these stories of persecution were so intertwined with who we were that they might as well have been holy stories. I knew that the religion lived in the men and women who had been born to preserve it, and that I was one of them.” To Nadia, however, the previous genocides belonged to a distant past. The ongoing violence in Iraq and neighboring Syria also did not feel like part of the contemporary plight of Yazidis – until one day ISIS began to surround Kocho and the Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga forces fled, leaving them unprotected.

Nadia dreamed of either becoming a history teacher or opening a hair salon in Kocho, Iraq – a small village of farmers and shepherds in southern Sinjar. In her book, The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State (2017), Nadia talks about growing up with her many brothers and sisters amidst a tight-knit Yazidi community. Central to Yazidi identity is the history of the seventy-three past firmans (to mean genocide) committed against the community by outside forces. Nadia, along with others Yazidis, learned about this history but never thought she herself would soon survive a genocide against her own religious community. Nadia writes, “…these stories of persecution were so intertwined with who we were that they might as well have been holy stories. I knew that the religion lived in the men and women who had been born to preserve it, and that I was one of them.” To Nadia, however, the previous genocides belonged to a distant past. The ongoing violence in Iraq and neighboring Syria also did not feel like part of the contemporary plight of Yazidis – until one day ISIS began to surround Kocho and the Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga forces fled, leaving them unprotected.

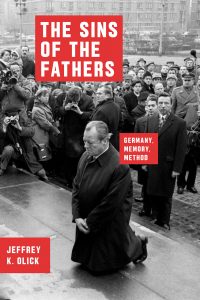

There is no state that has been and continues to be as haunted by the specters of a criminal past as is Germany. What happens when State leaders cannot tell a positive story about the nation’s past? A damaged national identity is, of course, not unique to Germany. For German leaders, however, the task at hand was, and continues to be, the mastering of a past that has become the symbol of ultimate evil. Jeffrey Olick’s The sins of the fathers: Germany, memory, method examines, with an impressive wealth of documentation and meticulous attention to detail, the process by which the Federal Republic of Germany (1949–1990) confronted the burden of the Nazi crimes and dealt with its political costs.

There is no state that has been and continues to be as haunted by the specters of a criminal past as is Germany. What happens when State leaders cannot tell a positive story about the nation’s past? A damaged national identity is, of course, not unique to Germany. For German leaders, however, the task at hand was, and continues to be, the mastering of a past that has become the symbol of ultimate evil. Jeffrey Olick’s The sins of the fathers: Germany, memory, method examines, with an impressive wealth of documentation and meticulous attention to detail, the process by which the Federal Republic of Germany (1949–1990) confronted the burden of the Nazi crimes and dealt with its political costs.

Germany’s ‘legitimation profiles’

Jeffrey Olick argues that ‘much of the state-sponsored memory in the Federal Republic of Germany has been organized as an effort to deny collective guilt’ (p. 29). The book is structured around the presentation of three succeeding ‘legitimation profiles’ – each confronting the problem of collective guilt in singular ways.

The first one, the ‘reliable nation’, which was centered on institutional reform, rather than symbolic gesture, aimed to prove that the newfound German state was a trustworthy and responsible member of the international community. During this time, the country’ s leaders draw a clear line separating the criminal Nazi leadership from the general German population. The Nazis had committed crimes ‘in the name of the German people’, as chancellor Adenauer put it in the1950s.

The recent “Truth, Trials and Memory Conference” at the University of Minnesota revealed an often overlooked concern in the field of Transitional Justice, namely that of the family, and its place and function for a forward-looking memory that is passed on from one generation to another. The panel on Memory in El Salvador took on a sentimental tone centered on the ideals and utopias held by one generation, as well as memories of political violence and victimhood experienced addressing how the next generation engages with them.

Professor Méndez participated this month in the International Conference Truth, Trials and Memory. An Accounting of Transitional Justice in El Salvador and Guatemala at the University of Minnesota. After his panel on “Truth-seeking Lessons from the Guatemala Experience”, he shared more insights with Michael Soto (UMN Graduate Student, Sociology).

After more than half a century of armed conflict, Colombia is poised to transition to peace. In 2016 a peace agreement was signed with the largest rebel group, the FARC, and there are currently negotiations with the second largest group the ELN. One component of Colombia’s transitional justice program is the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, which is charged with investigating and prosecuting human rights violations. Below, is the third part of their exchange on the peace process in Colombia.

Professor Méndez participated this month in the International Conference Truth, Trials and Memory. An Accounting of Transitional Justice in El Salvador and Guatemala at the University of Minnesota. After his panel on “Truth-seeking Lessons from the Guatemala Experience”, he shared more insights with Michael Soto (UMN Graduate Student, Sociology). Below, is the second part of their exchange on truth-telling.

Some authors, such as Martha Minow, have suggested that truth commissions are “second best” accountability tools. Could you please share your thoughts in response?

She was writing about South Africa, and I think her writing was very significant, and a great contribution to the transitional justice literature. But South Africa is a very special place, and special circumstance. I think it is true that for South Africa, if amnesty was part of the game, that a truth telling exercise was second best, but it was good to have. And I still think that the truth commission in South Africa made some great contributions.

Professor Méndez participated this month in the International Conference Truth, Trials and Memory. An Accounting of Transitional Justice in El Salvador and Guatemala at the University of Minnesota. After his panel on “Truth-seeking Lessons from the Guatemala Experience”, he shared more insights with Michael Soto (UMN Graduate Student, Sociology). Below, is the first part of their exchange on peace processes. You can read the second part on truth-telling here.

Juan E. Méndez, a native of Argentina, is a Professor of Human Rights Law in Residence at the American University – Washington College of Law, where he is Faculty Director of the Anti-Torture Initiative. In February 2017, he was named a member of the Selection Committee to appoint magistrates of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and members of the Truth Commission set up as part of the Colombian Peace Accords. He has previously held positions as UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, an advisor on crime prevention to the Prosecutor, International Criminal Court, Co-Chair of the Human Rights Institute of the International Bar Association, President of the International Center for Transitional Justice, and the Special Advisor to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan on the Prevention of Genocide.

Juan E. Méndez, a native of Argentina, is a Professor of Human Rights Law in Residence at the American University – Washington College of Law, where he is Faculty Director of the Anti-Torture Initiative. In February 2017, he was named a member of the Selection Committee to appoint magistrates of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and members of the Truth Commission set up as part of the Colombian Peace Accords. He has previously held positions as UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, an advisor on crime prevention to the Prosecutor, International Criminal Court, Co-Chair of the Human Rights Institute of the International Bar Association, President of the International Center for Transitional Justice, and the Special Advisor to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan on the Prevention of Genocide.

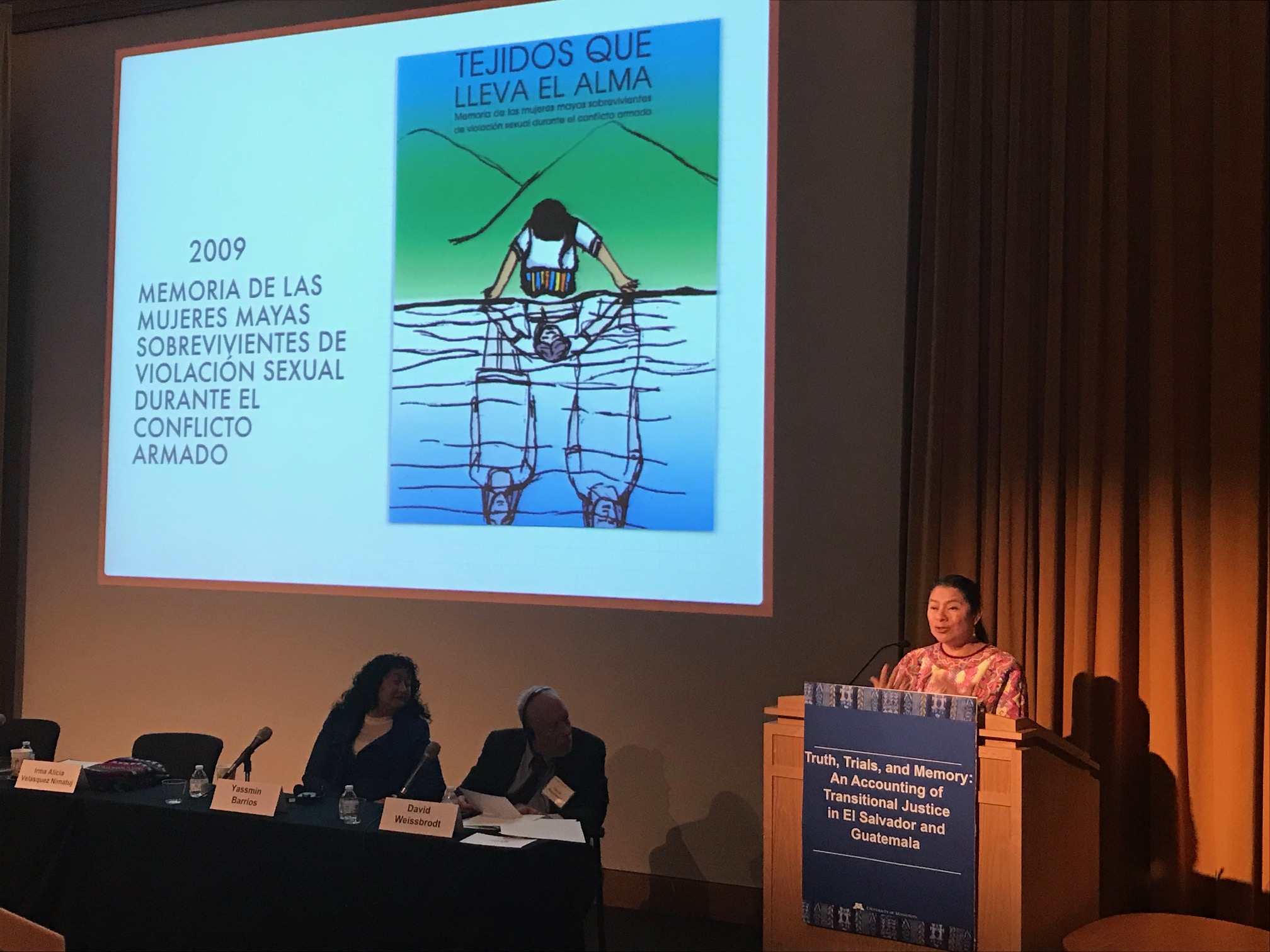

The “Truth, Trials, Memory” conference, held at the University of Minnesota between November 1 – 3 opened with an ambitious quest: twenty years after the historical clarification commission in Guatemala, what does accountability look like? Further, in a time of increased civil discontent, protest, and resistance sweeping the United States, what can we learn from transitional justice and indigenous Guatemalan liberation projects?

Keynote speaker Pablo de Grieff opened the conference by naming four key components to transitional justice work done in post-conflict contexts: establishing truth, activating instruments of justice, the dispersal of services and reparations to victims, and the guarantee of non-recurrence. Yet, as the conference rolled onward, it became clearer and clearer to panelists and audience participants the grave difficulties and consequences of such achievements.

Indigenous K’ichee’ anthropologist, activist, author, and journalist – as well as the main protagonist of Pamela Yates’ newest film 500 Years – Irma Alicia Velásquez Nimatuj concluded her presentation with a powerful response to transitional justice researchers and practitioners. After describing the story of a woman who had to flee her own community during the conflict with her husband and four children, only to return alone after the conflict ended, Velásquez Nimatuj declares (orig. Spanish):

I have fond memories of spending childhood Thanksgivings with my Slovak grandmother in Eastern Pennsylvania. Never a traditional meal, we ate city chicken and Serviettenknödel (a Bohemian dish not dissimilar to traditional dressing). The stories I heard around the dinner table were of the hardships of my immigrant family coming to the U.S. and, despite facing immense adversity, surviving and thriving due to honest hard work. Despite learning about the myths surrounding Thanksgiving and teaching my high school students about Indigenous genocides, it’s been only recently that I began to connect these stories to the larger narrative of U.S. settler colonialism. Maybe it’s because my holiday traditions seemed so rooted in my family’s immigrant past and stories of hardships and survival, which seemed so removed from the myths of Native and European encounters. Maybe it’s a reluctance to connect my happy childhood memories and traditions to ideas of genocide.