In the woods of northern Minnesota, tucked along the shores of Turtle River Lake, is a small German village called

The “Bahnhof,” or “train station,” at CLV Waldsee

Indeed, it wasn’t until 2017, when Alex Treitler stumbled upon references to the Nazi Waldsee while researching the CLV immersion program out of curiosity, that the issue was brought to the attention of the village’s leadership. In an article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Dan Hamilton, dean of CLV Waldsee, was quoted: “Frankly, we were just not aware […] I’m a professor of international relations, so we were a bit embarrassed.” Despite this initial embarrassment, CLV quickly convened a twenty-member advisory committee made up of academic and community experts to examine the issue and make recommendations.

In a recent presentation at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, “A Tale of Two Cities: Concordia Language Village’s ‘Waldsee’ in the Crucible of History and Memory,”* Sonja Wentling, Professor of History and Global Studies at Concordia College and a member of the advisory committee, shared the story of the two Waldsees. Wentling presented alongside four of her undergraduate students, Allison Hennes, Samara Strootman, Jarret Mans, and Colleen Egan, who had taken part in Wentling’s fall 2018 “Introduction to Historical Thinking Class,” which specifically took up issues of historical memory around the name Waldsee. The class was part of Concordia College’s PEAK, or Pivotal Experience in Applied Learning, Program, in which students apply classroom learning to real-world issues. As a part of the class, students conducted historical and archival research, spoke with Treitler and advisory committee members, and interviewed staff and students at CLV Waldsee. During the presentation, these students shared their experiences of “doing history,” rather than merely learning about history.

During the presentation, Hennes shared how the iso-immersion camp program was the brainchild of Concordia College professors Gerald Haukebo and Erhard Friedrichsmeyer, who initially chose the name Lager Waldsee, or “Camp Forest Lake” (the term “Lager,” also evocative of Nazi Concentration Camps, which, in German, are termed Konzentrationslager, was later dropped from the name). The camp first opened to students in the summer of 1961, the same week that the construction of the Berlin Wall began and in the midst of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust. Though seemingly secluded in the Northwoods of Minnesota, Wentling said that she and her students soon discovered that Waldsee “was not isolated from the events that took place thousands of miles away in Germany and Israel.” While the division and reunification of Germany have loomed large at CLV Waldsee, the Holocaust has not been a regular aspect of the village’s programming.

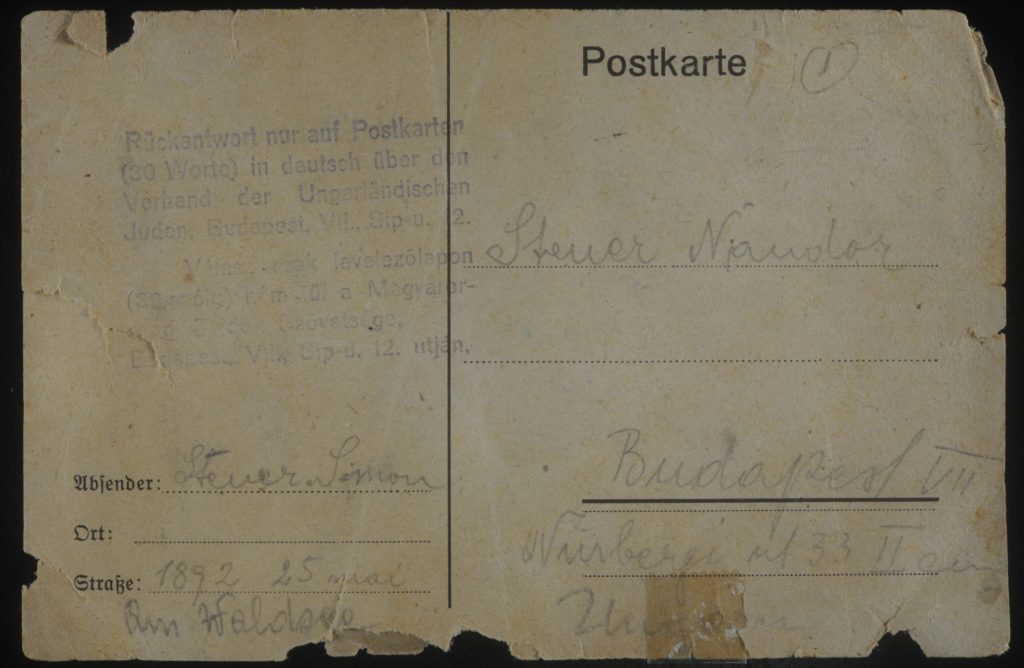

Strootman discussed how the term Waldsee, used as a euphemism for Auschwitz by the Germans during the deportations of Hungarian Jews, was mostly unknown in the West due to Cold War-era divisions. Though, its use was undoubtedly known to many academics and survivors and started to emerge in more popular works by the mid-1990. Indeed, Imre Kertesz, the Hungarian writer and Holocaust survivor who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2002, referenced Waldsee in the opening pages of his semi-autobiographical novel Fateless, which, though published in 1975, first appeared in English translation in 1992). Kertesz wrote: “I am completely ignorant how (but some adults did discover it) we learned that our journey’s end was a place named Waldsee. When I was thirsty or hot, the promise contained in that name immediately invigorated me.” An exhibit created in 2004, “Waldsee 1944,” put the Nazi deception on display, showing postcards that Hungarian Jews who were deported to Auschwitz sent back to relatives postmarked “Waldsee.”

Postcard sent by Simon Sandor Steuer from Waldsee, Germany to Nandor Steuer in Budapest on June 14, 1944 (Yad Vashem’s Digital Collections)

The lecture concluded with a discussion of CLV’s ongoing and future efforts to address the Waldsee name. Egan discussed how the “Waldsee 1944” exhibit was prominently displayed at Waldsee’s Biohaus during the summer of 2018, may become a permeant feature of the camp. Mans spoke about the possibility of including an empty postcard rack in Waldsee’s Laden (village store) with a sign that might read “ask us why we don’t sell postcards here.” It would seem, however, that there is some trepidation around changing the name of the village. “We have begun pulling at a loose thread—and that’s been good—but we don’t want to unravel the whole cloth,” says CLV Executive Director Christine Schulze. Though CLV Waldsee will retain its name, efforts will be made to ensure students and staff are aware of the history. Wentling praised CLV’s “commitment to address history rather than run away from it.” Indeed, in a second statement to the community of current and former staff and students, CLV outlined several steps that will be taken in the coming year to address the Waldsee name and Holocaust education at the village and within the programming.

I worked as a credit instructor at Waldsee in the summer of 2008. At the time, I remember being surprised by this authentic-seeming microcosm of German culture in northern Minnesota, including listening to the German-language radio station, using Euros at the camp’s bank and store, and eating European-style bread made by German apprentice bakers at each meal. In retrospect, however, Waldsee seemed to lack the notion of an Erinnerungskultur (Culture of Memory), which is often used synonymously with Holocaust remembrance in Germany and Austria. At CLV Waldsee, where simulations are often used to help students understand a divided Germany during the Cold War or the current refugee crisis facing Europe, no one seems to want to undertake simulations of the Holocaust, nor should they! Though Waldsee presents students with a rich academic experience, it is also a summer camp, which makes discussions of the Holocaust seem somewhat out of place, albeit necessary. Hopefully, what began as a discussion over a name will lead to a meaningful look at how to best integrate Holocaust education into the Waldsee experience.

Wentling and her students’ presentations brought together an audience of students, professors, and community members, many with ties to CLV Waldsee, at a moment when the University of Minnesota community is debating changing the names of several buildings on its Minneapolis campus. One hopes that such debates, while necessary, similarly extend into conversations around learning about and from the seemingly absent episodes of the United States, Minnesota and the University’s difficult history.

* The lecture was sponsored by Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies with support from the University of Minnesota’s Institute for Global Studies, Center for Jewish Studies, Center for German and European Studies, Center for Austrian Studies, Department of History, and Department of German, Nordic, Slavic, and Dutch, as well as the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas.

George D. Dalbo is a Ph.D. student in Social Studies Education at the University of Minnesota with research interests in Holocaust, comparative genocide, and human rights education in secondary schools. Previously, he was a middle and high school social studies teacher, having taught every grade from 5th-12th in public, charter, and independent schools in Minnesota, as well as two years at an international school in Vienna, Austria.

Comments