“Now the depression of the reactionary government.… It is a disgrace, which gets worse with every day that passes…. Everyone’s keeping their heads down, Jewry most of all and the democratic press.… What is strangest of all is how one is blind in the face of events, how no one has a clue to the real balance of power.… Will the terror be tolerated and for how long? The uncertainty of the situation affects every single thing.” So wrote Victor Klemperer in his private diary on 21 February 1933, scarcely three weeks following Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany the previous month. A literary scholar and war veteran, Klemperer watched firsthand as the pillars of free society crashed down around him.

In the two weeks that followed this entry, as his supporters celebrated Germany’s so-called “national awakening,” Hitler granted a full pardon to every Nazi stormtrooper in prison and under investigation, restricted the freedom of the press as well as the right to organize and assemble, appointed his closest associates to positions unequal to their qualifications, and laid the groundwork for the Sturmabteilung (SA) and Schutzstaffel (SS) to establish a concentration camp in Dachau. “What, up to the election, I called terror,” Klemperer lamented on 10 March 1933, “was a mild prelude…. It’s astounding how easily everything collapses.” The following month on 3 April 1933, he conceded that “everything I considered un-German, brutality, injustice, hypocrisy, mass suggestion to the point of intoxication, all of it flourishes here.”

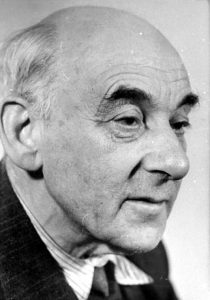

Klemperer’s private writings after Hitler’s Machtergreifung provide an unvarnished portrayal of the humiliation and terror that pervaded everyday life in the Third Reich. Though a chronicler of fascist violence, Klemperer did more than just observe acts of cruelty—he also lived them as well. The son of a rabbi, he converted to Christianity when he was a young man, only later to embrace his Jewish identity as an adult. While Klemperer saw himself as a German, the Nazis regarded him as “un-German,” a prejudicial worldview that eventually cost him his academic position, citizenship, and even his beloved cat, Muschel. “One is an alien species or a Jew with 25 percent Jewish blood,” he grieved on 10 April 1933. “As in fifteenth-century Spain, but then the issue was faith. Today, it’s zoology + business.”

Most are familiar with the genocidal crimes of the Nazis. Fewer people, however, are aware of the cumulative measures they instituted before the end of 1933 that destroyed Germany’s experiment with liberal democracy. Speed and deception proved essential in this effort. In the first months of the regime, the Nazis orchestrated a series of celebrations and staged pageants that enabled Hitler to hail his executive orders as the popular will of the people. Klemperer’s reflections illuminate both the human and political consequences of these initiatives. They also reveal how even Hitler’s most innocuous pronouncements degraded democratic institutions and normalized violence against minority communities.

His diary is a remarkable testimony on life in Nazi Germany told from the perspective of someone whom the state sought to degrade, marginalize, and ultimately eradicate from the population—and it makes for chilling reading today. Klemperer commented on a variety of topics between January and May 1933, from the pretense of law and public displays of aggression to interactions with former friends who supported Hitler electorally:

On law: “On the instruction of the Chancellor of the Reich the five men sentenced in the summer by a special court in Beuthen for the killing of a Communist Polish insurgent have been released (they had been sentenced to death!). The Saxon Commissioner for Justice [meanwhile] orders that the corrosive poison of Marxist and pacifist literature is to be removed from prison libraries, [and] that the penal system must once more be punitive…. We would more likely live in a state of law under French [colonial] occupation than under this government. This is truly no empty phrase: I can no longer get rid of the feeling of disgust and shame. And no one stirs; everyone trembles, keeps out of sight.”

On executive decree: “Every new government decree, announcement, etc. is more shameful than the previous one. In Dresden an Office to Combat Bolshevism. Reward for important information. Discretion assured. In Breslau Jewish lawyers forbidden to appear in court. In Munich the clumsiest sham of an attempted assassination and linked to it the threat of the ‘biggest pogrom’ if a shot should be fired. And the newspapers snivel…. Goebbels as Minister of Advertising. Tomorrow the ‘Act of State of March 21’! Are they going to have an emperor?”

On administrative dismissal: “The new Civil Service ‘law’ leaves me, as a front-line veteran, in my post—at least for the time being. But all-around rabble-rousing, misery, fear and trembling…. Everyday new abominations. A Jewish lawyer in Chemnitz kidnapped and shot. Provision of the Civil Service Law: anyone who has one Jewish grandparent is a Jew. A worker or employee who is not nationally minded can be dismissed in any factory, [and] must be replaced by a nationally minded one. The NS plant cells must be consulted. For the moment I am still safe. But as someone on the gallows, who has the rope around his neck, is safe. At any moment a new ‘law’ can kick away the steps on which I’m standing and then I’m hanging.”

On propaganda: “Is it the influence of the tremendous propaganda—films, broadcasting, newspapers, flags, ever more celebrations? Or is it the trembling, slavish fear all around? I almost believe now that I shall not see the end of this tyranny…. They are expert at advertising. The day before yesterday we saw (and heard) on film how Hitler holds his big rallies. The mass of SA men in front of him, the half-dozen microphones in front of his lectern, which transmit his words to 600,000 SA men in the whole Third Reich—one sees his omnipotence and keeps one’s head down. And always the Horst Wessel Song. And everyone knuckles under.”

On individual support for the new government: “Unfortunately on Tuesday evening we had the Thiemes here. That was dreadful and the end of that. [Herr] Thieme—of all people—declared himself for the new regime with such fervent conviction and praise. He devoutly repeated all the phrases about unity, upwards, etc. Trude [Thieme] was harmless by comparison. Everything had gone wrong, now we had to try this. ‘Now we just have to join in this song!’ [Herr Thieme] corrected her vigorously. ‘We do not have to,’ the right thing was truly and freely voted for. I [Klemperer] shall not forgive him that…. He runs with the pack. But why to me? Caution in the shape of utterly consistent hypocrisy? Or can he simply not think clearly?

On futility: “Ever more hopeless. The [Jewish] boycott beings tomorrow. Yellow placards, men on guard. Pressure to pay Christian employees two months salary, to dismiss Jewish ones…. In Munich Jewish university teachers have already been prevented from setting foot in the university. The proclamation and injunction of the boycott committee decrees ‘Religion is immaterial,’ only race matters.”

Klemperer’s accounts during the first months of Nazi rule pulse with emotion. They scorn the authoritarian nature of the government and lament the fate of basic human rights in German society. Once previously uncontentious privileges, such as freedom of religion, the right to an education, and equality before the law, were now at the mercy of a reactionary, all-knowing, lazy man who demanded total allegiance and unwavering praise at all times. “How wretched,” Klemperer scorned. “Gratitude to Hitler—even if the racial question has not yet been clarified, even if the ‘aliens’ … have made important contributions—we thank Hitler, he is saving Germany!”

One does not need a Ph.D. in German history to make judicious comparisons between the events Klemperer imparted in his diary and present-day affairs. Like in 1933, the most vulnerable individuals today are minorities, notably members of the LGTBQ+ community, people of color, and those in search of political asylum. “The defeat in 1918 did not depress me as greatly as the present state of affairs,” Klemperer wrote on 17 March 1933. “It is shocking how day after day naked acts of violence, breaches of the law, barbaric opinions appear quite undisguised as official decree.” We would be wise to dismiss the false logic that regards state-sponsored discrimination as a unique aspect of Germany’s recent past. History does not repeat itself. But a critical evaluation of historical events can at least provide us a means to learn about the destructive capabilities of nationalism, racism, and centralized oppression. We need look no further than Victor Klemperer and his courageous effort to “bear witness” for such an appraisal.

The remarkable historian and my late advisor, Dr. Eric D. Weitz, wrote extensively about the dangerous potentials that made human rights abuses possible after the French Revolution. He was an unequivocal champion of diversity and liberal democracy, and feared any effort that sought to forge a “homogeneous” society. I have often thought of him during my current research sabbatical in Berlin. In the past weeks, however, I have mostly thought about his closing words in Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy (2007): “The threats to democracy are not always from enemies abroad. They can come from those within who espouse the language of democracy and use the liberties afforded them by democratic institutions to undermine the substance of democracy. Weimar cautions us to be wary of those people as well. What comes next can be very bad, even worse than imaginable.”

Memorial plaque outside Victor Klemperer’s former apartment building in Berlin. The text below his name reads: “In his diaries from the time of the National-Socialist dictatorship, he left behind a unique testimony about the everyday persecution of Jews in a German city.” Source: Author’s photo, 26 January 2025.

Dr. Adam A. Blackler is an associate professor of history at the University of Wyoming. He is serving as a visiting professor of history at the Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut of the Freie-Universität-Berlin for the 2024-2025 academic year. Dr. Blackler is a historian of modern Germany, whose research emphasizes the transnational dimensions of imperial occupation and settler-colonial violence in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His scholarly interests also include the political and social dynamics of Germany’s Weimar Republic and the interdisciplinary fields of holocaust & genocide Studies and international human rights.

Comments