As a queer activist and researcher from Turkey, I am interested in understanding how queer lives endure in post-genocidal Turkey. I dwell on the Armenian Genocide and how the denial of the genocidal past is adapted by the sovereign Turkish state as a form of governing strategy (Savelsberg 2021, Suciyan 2017). More specifically, I contemplate how the circulation of denial is also related to the endurance of heteronormativity in which the broader practices of sexual violence, forced religious conversion, and orphanage emerge as critical issues (Ekmekçioǧlu 2015, Maksudyan 2015).

I hope to examine how the dissolution and disruption of Armenian families are linked to the reproduction of normative gender relations and the endurance of violence. By bringing queer and Armenian communities together, I concomitantly examine post-genocide, Armenians, and queer as bounded livelihoods in which the production of gender & sexuality and ethnicity are not necessarily separate categories but vividly intersected.

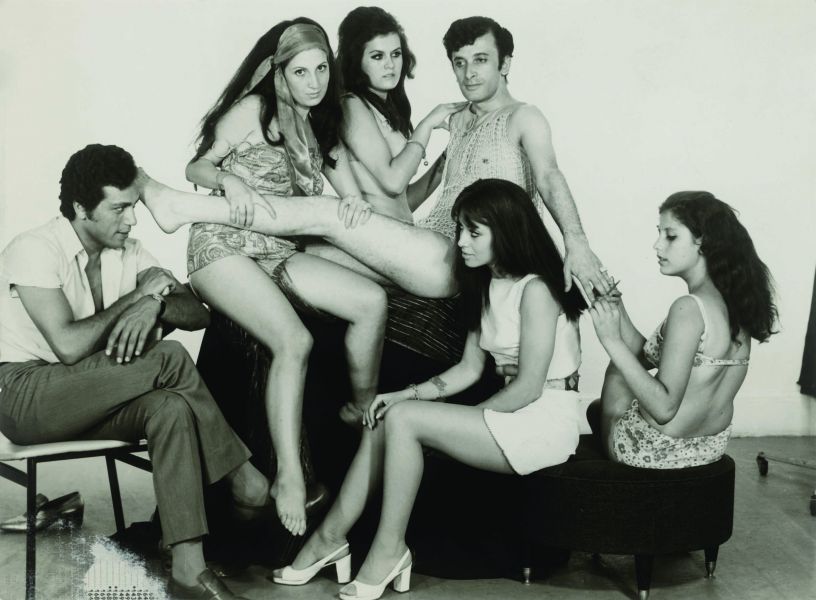

I have come to study this topic through my master’s thesis. I studied the ways in which the military coup of 1980 marked queer generations born before and after the event as radically different in Turkey. I studied the category of elderly queer by thinking through mass violence, intergenerational relations, and the emergence of global queer politics. I revealed that the military coup of 1980 disrupted the intergenerational relations in the queer communities and accelerated the adaptation of global sexual identities such as lesbian and gay. This research was informed by the funeral of Armenian queer photographer Osep Minasoğlu, who died at the age of 84 in Istanbul.

Even though my research has shifted from elderly queer to the study of social difference through the dynamics of the Armenian Genocide and its contemporary iterations, the funeral of Minasoğlu has remained a cornerstone of my scholarly orientation. This elderly man was a liminal figure, and his funeral posed a critical question for me to trace the intersection of queer and Armenian communities.

Minasoğlu has suspended the integrity of the queer identity by problematizing the taken-for-granted assumptions about ethnic singularity and sexual disposition. In other words, his life-course showed that queer movement implicitly reproduces heteronormative Turkish nationalism without interrogating how it sustains the one-dimensional queer subject as Turk and Sunni-Muslim. The life of Minasoğlu, however, helps us to pose the question of what happens when different ethnicities and religious subject-positions come into picture concerning the queer lives in Turkey.

I was paralyzed at the funeral, considering my inability to navigate a funeral ceremony taking place in a church and my lack of engagement with the Armenian community. As a queer man, I not only implicitly encapsulated my Sunni-Muslim and Turkish ethnic identity, but I was also not necessarily interrogating my positionality, which unconsciously ignored the genocidal atrocities continually resurfacing in contemporary Turkey. I started to think about how the queer movement implicitly reproduces nationalist ideologies of the Turkish state without raising the issue of the Armenian Genocide and its recognition.

The funeral of Minasoğlu, in time, has turned into racial melancholia imbued with the shame stemmed from the vicious dispossession of Armenian families and brutal (re)enactments of extermination strategies (Cheng 2001, Parla & Ozgul 2016). I engage with Minasoğlu, not as a ghost of the past, but I attempt to bring him to the present moment, conceptualizing his dead body as a social figure that enacts ramifications of post-genocidal society (Gordon 2008, Yashin 2012).

My interest in his biography motivated me to learn more about the Armenian Genocide and the experiences of survivors. As a result, I shifted my project to study the ways in which social difference is produced, contested, and reframed in contemporary Turkey. I hope to ethnographically document how the sovereign Turkish state reproduces its hegemony over minorities along with reproducing normative gender relations and forging communal boundaries.

My broader Ph.D. dissertation project deals with how queer and Armenian communities have unexpectedly come together in strange ways. For example, I consider communal boundaries, reproduction of normative gender relations, the endurance of queer lives, and emerging socialities between minorities.

Berkant Çağlar is a Ph.D. student in Sociocultural Anthropology at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. He received his BA in Media and Communication and Sociology from Izmir University of Economics. He has an MA in Sociology from Bogazici University. He is broadly interested in the anthropology of mass violence and genocide, anthropology of the state, haunting, care, LGBTQI aging studies, and Bourdieusian social theory.

Comments