The Center has been busily promoting the work of Professor David Feinberg, who has retired from the Department of Art after an illustrious 50-year career. A retrospective of Feinberg’s work is currently on display at the Katherine E. Nash Gallery on the UMN West Bank Campus.

The works on display serve as important reminders, best summed up in Feinberg’s own words:

“All art comes from the unconscious. The unconscious makes connections between the past and the present. Truth has to be found, not contrived or preconceived. Seeking truth is the way to originality. The only true thing a person has is their unique perception of the world.”

The exhibition, Divide Up Those in Darkness from the Ones Who Walk in Light, consists of two collections: Voice to Vision and a collection of Feinberg’s earlier works. Upon walking into the gallery, one first sees several of these early pieces on display, encouraging visitors to immediately engage with an overarching theme of the retrospective: the role of art for the individual—not only to shape public consciousness but also larger arcs of history. Subjects of these early pieces include partisans active during World War II, the 1956 explosion at the Brooklyn piers, the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, and the “Day the Music Died” to name a few.

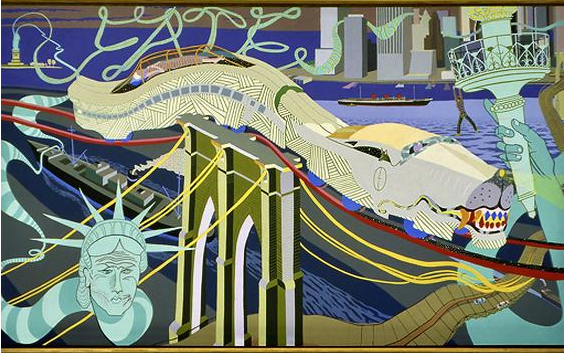

The multimedia pieces in the exhibition include wood construction, collage, and other materials from photographs, news sources, etc. Extraordinary 2D/3D works depicting interior spaces, along with pieces that echo surrealist trends from the 20th century, stand alongside Feinberg’s “Kaddish for the Immigrant’s Son.” At 82 x 148 inches, the painting prominently features New York landmarks such as the Statue of Liberty, with its head and torch trailing throughout the painting, and containing the transliterated words of the Kaddish (one of the central elements of the Jewish liturgy).

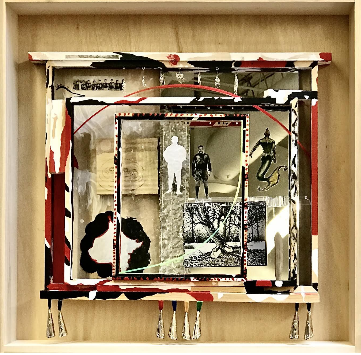

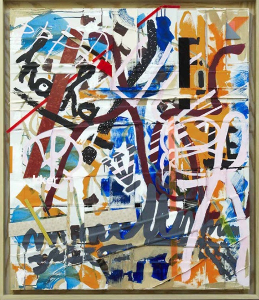

Over half of the retrospective is devoted to Feinberg’s Voice to Vision, a groundbreaking “memory project” focused on collaboration with survivors of genocide. Voice to Vision uses painting, drawing, collage, and mixed media to center individual survivors, who can often be lost in narratives dominating textbooks and public consciousness. Oral and visual testimony also takes a central role in the Voice to Vision artwork, which is clear as one walks through the gallery spaces.

For example, genocide survivors from different parts of the world first share their stories through dialogue, and the stories, in turn, transform into works of visual art produced by the survivors themselves and a larger collaborative team. According to the exhibition program, approximately 200 people have been involved with Voice to Vision.

Brenda Child, Steve Premo, Benay McNamara, David Feinberg, Beth Andrews, Reid Luskey, Adolfo Menendez, Stefanie Suhon, Joey Feinberg.

Source: CHGS Elevator Site

Various series from the Voice to Vision Collection also put into dialogue different episodes of genocide and mass violence, thereby emphasizing that individual experiences—even if disparate—can illuminate rather than obscure human rights abuses as they continue to occur across time and space. In one particular piece from Voice to Vision III, “Romania 1941/Rwanda 1994,” draw on memories and sounds of survivors’ pasts that then appear in the multimedia artwork itself. Descriptions beside each work provide background information as well as the forms of collaboration that took place between survivors and artists to make each piece possible.

David Feinberg. Drawing contributions from Romanian survivors Max Goodman and Edith Goodman, Rwandan survivor Alice Tuza and her sister Floriane Robins-Brown, with artists: Caroline Kent, Kelly Frush, David Harris, and Solomon Atta.

Source: CHGS Elevator Site

Each art piece emerged through close collaboration between artists and genocide survivors, all of whom exchanged ideas and made creative decisions together. The accompanying documentaries also feature original scores. This additional level of collaboration with musicians helps to shape the sound surrounding the survivor’s stories. As I walked through the exhibit, it is certainly clear from the screens playing the accompanying documentaries that sound (as well as the visual) plays an important role in public memory.

The audiovisual recordings of the testimony produce another important effect for the viewer; the convergence of each voice involved in the project becomes part of an interactive journey through the gallery. The video documentaries will allow survivors, respective communities affected by genocide, and future generations to experience crucial aspects of the project beyond the artworks produced. These videos are also available on the CHGS Elevator site.

Feinberg’s goal of the Voice to Vision project was to inspire others and to use the tools of dialogue and the visual arts to investigate, recover, and protect the narratives and emotional experiences of genocide survivors. The combination of physical art pieces and video documentaries can connect audiences to life-changing moments in history, and will stimulate discussion and education surrounding the events in question.

The exhibition, Divide Up Those in Darkness from the Ones Who Walk in Light runs until December 11, 2021.

Olivia Sailer is an undergraduate student working for the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Sailer is currently a junior and is majoring in Anthropology, with a focus on the sociocultural and linguistic subfields.

Meyer Weinshel is a Ph.D. candidate in Germanic studies at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, where he is the educational outreach and special collections coordinator for the UMN Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. In addition to being an instructor of German studies, he has also taught Yiddish coursework with Minneapolis-based Jewish Community Action and at the Ohio State University.

Comments